Craft

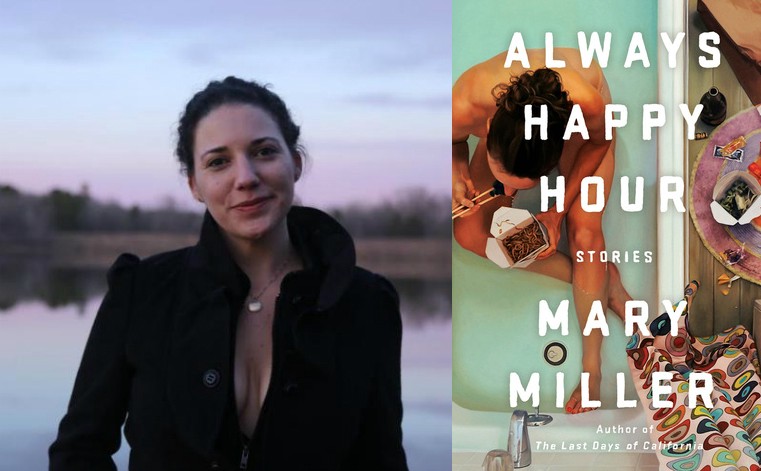

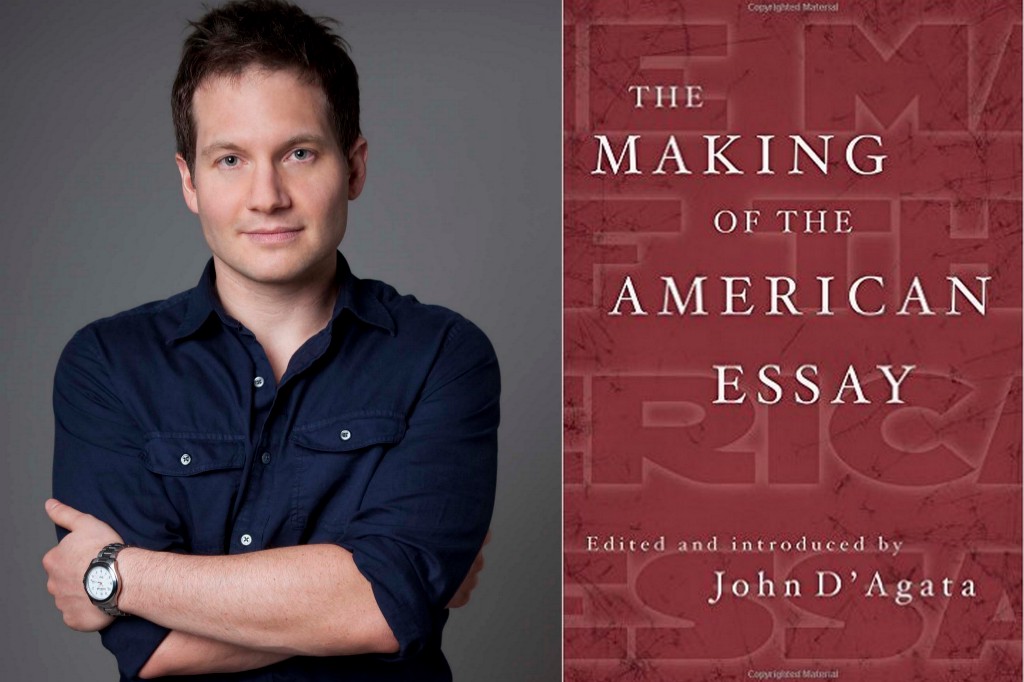

John D’Agata Redefines the Essay

Susan Steinberg Talks with the Editor of The Making of the American Essay about Facts, Lies and the Art of Consideration

John D’Agata’s lyric essays — and his defense of the essay as art form — have been at the center of an ongoing discussion on the roles of fact and truth in the literary arts. His newest anthology, The Making of the American Essay, the third in a series, has sparked even more debate over the very definition of essay, what falls under the category, and the significance of — and suspicion of and resistance to — artistic invention. D’Agata has generously responded to a few of my questions on these topics, as well as on genre, lies, punishment, pleasure, and social media.

— Susan Steinberg

Susan Steinberg: I often try to explain what you mean when you speak of the essay as different from nonfiction — when you refer to the act of “essaying.” You described this to me a few years ago, and I was listening to you, but I since have become unable to articulate what you said. I tend to land on “it’s about the process, not the product,” but I find myself saying that about most things. Can you repeat what the essay, to you, is? Or does?

John D’Agata: I like to think of the essay as an art form that tracks the evolution of consciousness as it rolls over the folds of a new idea, memory, or emotion. What I’ve always appreciated about the essay is the feeling that it gives me that it’s capturing that activity of human thought in real time. I think that feeling is what we all respond to in essays: the sense of intimacy that essays give us when we’re made to feel privy to another human being’s thought process. Our minds might be the only truly private spaces that any of us possesses, so to be given access to another person’s mind in an essay can feel wonderfully thrilling. I think that’s why Michel de Montaigne used that Middle French word to describe this literary form in the 16th century: essai. It means “to test, to attempt, to experiment.” The essay celebrates what makes us human because it celebrates thinking. It doesn’t celebrate polemics or fact-checking or whatever else our high school teachers turned it into. It celebrates the art of consideration.

Steinberg: Your anthologies are comprised of writings that some might argue aren’t essays. I argued, in fact, that my story was a story and not an essay, when you first got in touch with me about including it in your most recent anthology. I wanted to defend it as a fiction, in large part because I didn’t want to misrepresent the piece or myself; my concerns were of both a personal and a professional nature, and I now suppose they were somewhat fear-based. So my question is: have other writers or editors challenged your categorizing of the work you select, and what do you make of the attempts to maintain these genre distinctions?

D’Agata: The first anthology in the series, The Next American Essay, includes a short story by Susan Sontag entitled “Unguided Tour,” and suffice it to say, she wasn’t happy with my decision to include her story in the book. Just before the book came out I got an earful from her in a letter that knocked me sideways. She insisted that her story was a story and that it shouldn’t be interpreted as anything else. Unfortunately, the book was already in production by the time she sent that letter, so all I could do was write to her and try to explain why I’d decided to include her story, which is the same reason why I’ve decided to use a good number of other texts throughout this series of anthologies that are actually stories or poems. It’s not to reclaim them as essays, but it’s instead to try to think about essays from a different angle.

When a chapter from Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick appears in The Making of the American Essay, it shows up in the midst of a bunch of essays that have long been celebrated as essays — texts by Emerson, Thoreau, Mark Twain, etc. And so at this point in the anthology we’ve got essays on the brain. We’ve started noticing patterns in those texts, a kind of “essayistic” sensibility that’s recognizable no matter what sort of subject matter it’s applied to. But then: Moby-Dick shows up, and we’re probably thrown off our guard. What I hope, however, is that we are reading this anthology with an open mind and that we are willing to go along with that text’s inclusion for at least a moment, and thus that we are willing to temporarily imagine that that chapter from Moby-Dick is indeed an essay.

So say we do that. Say we read that piece of Moby-Dick in the context of all of those other essays that surround it in the anthology. Does that section of Moby-Dick read differently? Do we see anything in it that’s similar to the other texts around it? Can we recognize the same essayistic movements in Melville that we’ve been noticing throughout the rest of the anthology? And, if we can, then what does that mean? Does it change our perception of Moby-Dick? Does it change our perception of the essay?

What is an essay, after all, if we can see it working as a propulsive force in fiction or poetry? Can we call the essay its own genre if it’s so promiscuously versatile? Can we call any genre a “genre” if, when we read it from different angles and under different shades of light, the differences between it and something else start becoming indistinguishable? If our perception of a text can so easily change the moment that text is placed in a different context — an essay collection one day, a poetry collection the next — is it possible that the borders between genres are not the towering blockades that some people fiercely defend them as?

When The Next American Essay came out, I sent a copy of the book to Ms. Sontag along with my sheepishly argumentative letter, and she replied with a postcard that basically said “Okay. I sort of see what you’re trying to do. Signed, Susan Sontag.” I took it as a compliment.

Steinberg: If memory is unreliable, perspective is subjective, and emotion is unfixed, then what is the function and/or responsibility of “fact” in essays? I ask because I’m curious about your relationship to fact, but I’m also curious about your thoughts on readers’ fixations on the notion of truth. If a misconception about essay writers is that they’re truth-tellers, then do they often run the risk of disappointing the reader? How can essay writers confront or undo what seems to be an impossible-to-fulfill expectation?

D’Agata: Facts are akin to images, for me. That probably strikes some as a perverse statement, but I say it as someone who turns to essays for literary experiences only, and for that reason, when I’m reading I don’t need facts to do much more than resonate with the rest of the story that’s being told.

But that’s not the case with every reader, of course. We’re all looking for different things and have different expectations when we read. Yet for that very reason we do a disservice to both the essay and its readership by suggesting that everything that falls beneath the umbrella of “nonfiction” ought to be written by the same rules and for the same audience. There are some nonfiction books that traffic primarily in facts, by which I mean that we value them for the facts and information that they introduce to us and the ways in which they organize them. And those books are great. I’m a rabid reader of history and science, for instance, and I turn to those genres because I want the information that their dustjackets proffer: A Story about X and How It Changed the World. And while I appreciate those books being well written and am always down for great storytelling, I’m not necessarily expecting that from those books or looking for that when I read them. When I read a memoir, on the other hand, I’m hoping to bear witness to an exhilaratingly expressive voice and am therefore expecting a completely different literary experience. I don’t care about the facts in that case; I care about the story.

Writers can help the issue by not insisting that everyone else write their “nonfiction” the same way they do.

Writers can help the issue by not insisting that everyone else write their “nonfiction” the same way they do. When my book The Lifespan of a Fact came out and started ruffling some feathers, there were a lot of famous writers who went out of their way to distance themselves from the book by denouncing it in self-serving ways. Some wrote op-ed letters or spoke up at writing conferences or Tweeted vigorously in order to declare that they would never do what I was advocating in the book. And I get that. Or, I mean I kind of get that. On some level I understand where that was coming from because the book was openly discussing a taboo subject in the nonfiction world, and it’s hard to cleanse yourself of that kind of taint once it gets on you. So distancing yourself as much as possible makes sense.

Yet on the other hand, aren’t we artists? Isn’t one of the duties of art to explore the outer reaches of our media, to go to places that our culture says are off-limits? It seems a little cowardly — or at least ungenerous — to attack someone just because they make their art in ways you do not want to make yours.

Steinberg: Do you feel there’s pleasure associated in punishing the essay writer who has been “caught in a lie”? Is punishing is too strong a word?

D’Agata: “Punishing” is probably too strong a word, as is “pleasure.” Catharsis might be more accurate. I think some people probably feel empowered by attacking writers whom they think have wronged them. Others of course may feel pressured to do it. Oprah’s decision to chastise James Frey was due to the pressure that she felt from her fans after it was revealed that some parts of his very popular memoir — which she helped make popular when she selected it for her book club — had been exaggerated. I think that’s why she decided many years later to apologize to Frey, because she realized that she’d been bullied by popular opinion. I found it interesting that she chose to apologize to him in private, however, rather than on her show.

Of all places, literature and art should be where uncertainty can be explored and is relished and even championed.

So while I’m not sure what is accomplished by “punishing” such a writer, I do understand the cathartic benefits of doing it. Our economy’s wobbly, our security’s being threatened, and who knows what’s happening politically right now? We’re chatting during a season in which the Republican nominee for the next presidential election is spewing inaccuracies on almost a daily basis, and for some reason no one seems able — or willing — to hold him accountable. It’s hard to know what to trust. So it makes sense that a book which presents itself as x yet turns out to be y would frustrate and anger some readers because we’re frustrated up the wazoo with everything else that’s going on. But the problem with getting angry at that kind of instability is that our anger is misdirected. Of all places, literature and art should be where uncertainty can be explored and is relished and even championed. It might make you feel better to tell me that I should kill myself (as someone did after my last book) because you don’t like how I wrote something, but the problem with that reaction is that 1) I’m not going to kill myself, and 2) you’re shutting yourself off from the very literary experience that I’m trying to offer. A lot of my work is about questing certainty, questioning genre, questioning the very assumptions that we make about the world.

Steinberg: What might a “lie” in an essay look like?

D’Agata: For me, a “lie” is something that feels incorrect on the page, which I think is the difference between verifiability and veracity. Something that’s verifiable can be fact-checked beyond the world of the text. But veracity — or truthfulness — speaks to the believability of what’s on the page and what’s going on in the world that has been created by the author. While reading, if I can move through a text without wondering whether or not what I’m reading is “real,” then that text has done its job of capturing the truthfulness of whatever it is that it’s exploring. And that’s what I’m looking for when I’m immersed in a literary experience.

But it’s a whole other story beyond the realm of literature. When I’m reading a news article about the banking industry, or a medical textbook about how to fix my heart, or a set of instructions on building a suspension bridge, I’m not looking for a literary experience. I want every fact in those texts to have been verified multiple times. We do the literary essay a disservice, however, when we expect from it the same kind of verifiability as we would from a medical text book.

Steinberg: As a fiction writer writing first-person narratives, readers ask if I did the things my narrators do. In these moments, which I would argue are often gendered, I know I can exercise the right to hide behind the word “fiction” as a polite way of saying “what difference would it make if I did (or did not).” How do you, as an essay writer, maintain a separation between you (John, the person) and your characters, aesthetic choices, and narratives?

D’Agata: There is a separation. I don’t know how else to say it: there just is one. The history of the essay is a history of personas, and of writers using those slanted versions of themselves to tell bigger stories than themselves so that they can explore bigger themes. Throughout the essay’s history the persona has been the vehicle that has propelled this genre into the stickiest and most evocative places it’s visited.

The persona has been the vehicle that has propelled this genre into the stickiest and most evocative places it’s visited

It’s true, though, that a lot of writers have struggled with the contradiction of writing through themselves but not really of themselves. In the 16th century, Michel de Montaigne wrote extensively about the fabricated self that he was presenting on the page. “I may presently change,” he once wrote, “not only by chance, but also by intention.” In the 18th century, Charles Lamb admitted to “the assumption of a character . . . which gives force and life to writing.” Virginia Woolf struggled too between “Never being yourself and yet always — that is the problem.”

I think of it the way I imagine actors do, which is that while I’m definitely using some portion of myself in order to create a persona, the character that ends up on the page isn’t my full self. My previous book was a collaboration with a fact-checker called The Lifespan of a Fact which tried to address this. It replicated the exchanges that the fact-checker and I had while we were fact-checking one of my essays for a magazine. Because the argument in the book is partially about the “shaping” that’s necessary in all art forms, we recreated some of our exchanges, completely fabricated others, and cast ourselves as two characters that were loosely based on us but were not actually us. And in order to spice up the drama in the book, we each assumed an exaggerated role: he, the poor mistreated intern who’s heroically trying to nail down every fact in the piece; and I, the arrogant and pompous diva who won’t allow anyone to mess with his art.

When the book came out, we gave lots of interviews in which we talked openly about the fabricated nature of the book, and yet some people still insisted on reading those characters as real. Reviewers did it too. I was called a “jerk” by a few very famous publications because the assumption was that I was the “I” that appeared on that page. What this taught me is that even when we’re told otherwise, and even when we know otherwise, we still let the stranglehold of the term “nonfiction” dictate how we read something. We still insist on reading that “I” as a mirror of the author. And so now, in many people’s minds, I am that “jerk” that they read in The Lifespan of a Fact. I’d say this frustrated me if I didn’t find it so fascinating and baffling.

Steinberg: There is no perfect segue into this next question, though I believe it’s connected to much of what you’re saying about persona and reality and how we respond to writing. What are your thoughts/feelings about social media? And what are your thought/feelings, if any, about writing essays in the context of an online culture that’s manufacturing a seemingly endless stream of writings and visual texts many would call “essays”?

D’Agata: I don’t have any social media accounts, and I don’t follow any either. Actually, that’s not true. I follow a couple Instagram accounts of funny celebrities. I don’t consider those essays, though; I just consider them funny. I could imagine an Instagram essay, however — something that mixes image and text in an episodically narrative way for a defined extent of time, like during a trip or a pregnancy or something like that. I’m sure there are such essays already, in fact, but until Chris Pratt writes one I probably won’t encounter any.

But if you’re asking whether I’d call them essays? Yeah, sure. I haven’t seen any yet, but I don’t know why they wouldn’t be considered essays. Even a simple blog that explores the daily activities of someone’s dog can be essayistic. It might not be very good, but that doesn’t mean it’s not essaying the idea of dogness. There’s an awful lot of crappy fiction and poetry out there that’s still called “fiction” and “poetry” even though it’s lazy or derivative or panders to the broadest common denominator of readers. But it still gets to call itself fiction or poetry. Quality can’t be a standard for inclusion in a genre.

Steinberg: I, too, have avoided social media. Several writers have told me this is crazy, whereas others have congratulated me. Both responses seem exaggerated, and both reinforce my decision to stay away from it. I’m wondering why you’ve chosen not to use it.

D’Agata: I’m not sure I have an interesting reason for avoiding social media. I felt a little brutalized on Twitter and Facebook during the broohaha surrounding my Lifespan book, so some of my reasons might be a little transparent. I prefer not to invite other people’s feverish anxieties into my life. But I also just like my privacy, so I’m not really a great candidate for platforms that encourage users to share their every thought with the world . . . and every meal, workout, vacation photo . . .

Steinberg: At the end of The Making of the American Essay, you have included a note on the title in which you elaborate some on the word “making.” I confess that before I read this note, I was going to ask why you chose this particular word. But instead I’m going to ask what you think could be the “unmaking” of the American essay.

D’Agata: Not letting the essay essay, not letting it grow and explore and change as a genre. That’s what could be its unmaking: not letting the essay essay.

About the Interviewer

Susan Steinberg is the author of two story collections. The most recent is Spectacle, from Graywolf. Her work has appeared in McSweeney’s, Conjunctions, American Short Fiction, and elsewhere. She has held residencies at the MacDowell Colony and Yaddo, and teaches at the University of San Francisco.