Craft

Spooky Violins: On Discovering Another Poet’s Plagiarism

by Anonymous

[Due to the sensitive nature of this essay, I have removed the names of the poets, the university, the titles of poems and books, as well as the content of the cited poems. In other words, all poems in this essay are creations of the author, not the actual work in question.]

It is sleeting outside, the last day of the semester. It is a Friday, it is December. A Kleenex box, some hot tea. I am a little under the weather, so I’m staying in tonight, finally reading those books I’ve accumulated and craved. Mostly poetry found on Amazon’s “Recommended For You” list. Which one, which one? The blue one, the one with the soft cover, image of a woman in a tub, a wedding veil streaming over her.

I take medicine, make my tongue sour with cough drops. Undergrads pass my apartment, amazingly bare-legged in this weather. I heard it’s a snow emergency. A text from John, he wants to go on a movie date tomorrow, and I’m really into these poems:

My grief is always naked, it knows my old ghost.

I spend Sunday gazing at expired milk.

Outside, the rack and maple branch.

I could put this book on my Reading List, for my Master’s thesis. Maybe I could, it’s so good. And then, a feeling like déjà vu.

And the crickets hum,

playing their spooky violins.

I have read this before, haven’t I? So familiar, on the tip of my tongue now.

And I want to be so good,

want everyone to like my party dress.

I have read this before, I know. But how could that be? This book was only released last month. Did I read these poems in a magazine, maybe somewhere online? And then — ah ha.

A snowfall over my roof, over this small Midwestern town, all hushed. I rifle through my papers from the semester — the final portfolio drafts from our graduate poetry class.

I listen to bugs play

their spooky violins.

Oh god, oh no.

And you want to be so good

want them to like your dress

want to go back home.

Kelsey’s poems, my comments all over the page: “I love these images, so haunting and unusual.” I read the rest of the book and the portfolio, side by side. They’re everywhere, the images plucked and tweaked, almost identical in structure, tone, voice. At 5 am, I force myself to sleep, leave the lamps on all night.

* * *

A conversation on Facebook chat, the following morning:

Kels! this is crazy! I just read this book by — — — — — — — — and she has all these images that feel similar to yours! have you heard of her? if not, this book is super cool, you should check it out!

The benefit of the doubt. Perhaps there is an explanation — maybe it was a writing prompt. Yes, an experiment, borrowing from other sources to compose poems? As the day ticked onward, no reply. John took me to the movies, but I couldn’t concentrate, hardly touched the popcorn. An incantation: she knows, she knows, she knows I know.

An incantation: she knows, she knows, she knows I know.

That night, still no message. Surely, it can’t be that bad, right? The longer I wait for messages, for anything, the more my hands shake up, paranoia running across me. A sinking feeling. I block Kelsey on Facebook, on email, block her number on my phone. She knows I know, oh god, I want her gone, please disappear.

* * *

Kelsey, in a black babydoll dress, in septum piercing, in long eyelashes, her blush and cigarettes. Kelsey, blue hair, gray hair, black hair, always fragrant, always parsley and incense, tattoo of The High Priestess on her arm. It was her favorite tarot card and it was mine. Kelsey, the most talented writer in our class, the coolest girl I knew. Kelsey with oxblood Doc Martens, Kelsey with a chapbook press, with a poetry tour in the spring, with MFA applications out, these haunting poems inside. Just last month, she gave me a belated birthday gift — a small notebook she had hand-sewn, on the cover an image of two hands clasped. It’s a symbol of our friendship, she said. We’ll always be writing friends, long after we’re done here.

* * *

A few weeks after, I took myself home to Michigan, eight pounds lighter from illness and stress. I had lost my appetite, really. For those weeks, very little appealed to me. It was like recovering from a break-up, and in a sense, it was a break-up, the severing of a relationship. I was betrayed, yes betrayal was the word. I enlisted the help of another girl in the workshop, showed her my evidence, and we found the rest of it. We spent three days collecting, plugging Kelsey’s poems into Google, looking for the next clue. The images were thieved from everywhere — published books and magazines, mostly from young, up-and-coming poets that you probably wouldn’t find unless you were really looking, like we were. The final document of evidence was fifteen pages long. Nine different poets plagiarized in bits and chunks, images that I had once found so poignant, so unique, the magic gone now. I was horrified and I was proud. She almost tricked me, almost.

I enlisted the help of another girl in the workshop, showed her my evidence, and we found the rest of it.

We sent the email on a Monday morning, the evidence attached, sent it only to our workshop leader, although we wanted to tell everyone we knew. We were asked not to speak about it until after “the hearing,” which would take place in January when the semester resumed. I did tell my boyfriend, John and I told my family — we gossiped amongst each other and theorized what would become of Kelsey. I had my own ideas: Kelsey should be expelled from the Master’s program and excommunicated from all social circles. This is what I believed. It seemed fitting for the gravity of her crimes, her deceitfulness, her duplicity. Nothing had seemed amiss that semester, nothing “off” in her behavior. The Kelsey I knew, girl sitting across from me in a coffee shop, girl spending the night on my couch, girl with the velvet skirts and warmth, always thoughtful, bold, cool as hell. Henceforth, she was not to be trusted, everything false false false.

* * *

Email excerpt:

We regret to inform you of an unfortunate discovery made with regard to Kelsey’s work this semester. Attached is a document that highlights the similarities between Kelsey’s poetry and work by the poet

— — — — — — as well as poems written by — — — — — — , — — — — — — -, — — — — — — , — — — — — — , — — — — — — , — — — — — — , — — — — — — , and — — — — — — .

The closeness of the paraphrasing, in terms of syntax and content, as well as the extensiveness of the paraphrasing, leads us to believe that this is a case of plagiarism. It is an understood trust that all work submitted for the workshop is original or acknowledges credit where it is due. We feel Kelsey has breached this trust.

* * *

A September — almost a year later after the Kelsey incident — in Bloomington, Indiana. A poetry slam, a girl at the microphone with bracelets, high cheek bones, a lipstick one shade too dark. I’m sipping on a beer, a little thrill in my body, everything glimmering with newness, having just moved here. The girl begins performing. She does it so well, articulating each syllable, a momentum in her voice, everyone is snapping and going mmhmmm.

Again, a feeling like déjà vu. Something about her images, something too close for comfort. “A letter to my future daughter” — isn’t that what she called this piece? I know of a poem, a spoken word poem in fact, a poem so similar in its title, framework, cadence, it’s uncanny. The girl wins second place and a Barnes & Noble Gift Card. I can’t not say something. She has to know, she has to know I know. Surrounded by admirers, I make my way to this girl, tap her skinny shoulder, say as sweetly as possible: “I loved your poem! Have you heard of “ — — — — — -” by — — — — — — ? I think you would really like her work.”

She grins, mauve lipstick and a trilling laugh. “Oh yes, I adore — — — — — — -! She is such an inspiration! I kept thinking about her when I wrote that last poem, she was just stuck in my head.”

* * *

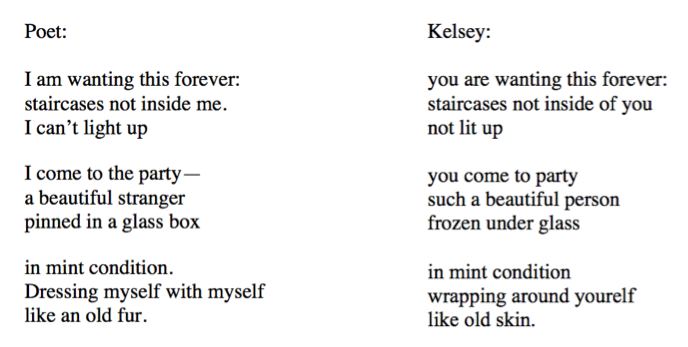

Evidence Excerpt:

* * *

When is it plagiarism, when is it homage? Especially in creative writing, I get tripped up on this distinction. A trick for writer’s block: write an imitation, steal moves, learn by mimicry. For my own poem-writing, I turn to other texts all the time. I pull language, take a word I like, sometimes fragments of phrases and twist them. I get inspired, I want to model after poems I fell madly for.

But how much do I really “make it my own?” When have I changed it enough that the poem is now in my possession, my creative and intellectual property? One of my students recently noted, “You can do anything in poetry, can’t you?” I answered yes, but qualified the statement: “As long as you don’t appropriate without acknowledgment.” Certainly, there are ways to acknowledge, maybe include a footnote or put beneath the title: “after [insert poet’s name].” What is the best way to do this? What are the rules exactly? Where is “the line?” Was what Kelsey did so wrong?

* * *

Kelsey was allowed to stay and complete her degree. To me, this punishment did not seem sufficient, not at all, and I felt a great injustice had been done.

I relished telling everyone what had happened, this juicy gossip I revealed behind closed office doors and at the local bar. Framing myself as the hero, quiet and suffering, so selfless, so brave for “doing the right thing.” At first, my peers were disturbed by the situation. What made Kelsey think that was okay?

I relished telling everyone what had happened, this juicy gossip I revealed behind closed office doors and at the local bar.

But in the following months, most everyone forgot their anger. They conceded that Kelsey’s punishment was harsh enough. When we would go out for drinks, no one wanted to discuss it anymore — a tired topic. Old acquaintances began avoiding me, or so I thought, maybe they were too caught up in their thesis projects or job hunting or their relationships. But to me, ironically, I felt I was the “trouble-maker” now, making trouble because I could not forgive Kelsey, refused to move on.

And so she remained, a phantom, still sitting in my classes, now at the other end of the seminar table, not in the chair next to me. I pretended she was invisible, avoided speaking to her, blocked her entirely from my field of vision. I wanted to shame Kelsey, to the point where she would realize that she didn’t belong here, that she would decide to remove herself and vanish, just like that — poof.

I suppose, too, I avoided Kelsey because I was frightened of her, of what lurked there under the eyes. Surely she knew, from the Facebook message I had sent back in December, she must know that I was the one turned her in. And I grew panicked because Kelsey could be volatile, or so I had heard. I’d never seen her hurt anyone, but at parties I didn’t attend, she would drink too much, get upset, throw a punch. One time, or so she told me, during a party, she wandered into the woods behind her house, drunkenly tripped on a tree root and she fell, got scratched up on the way down. When I fell, I decided not to get up. I lay on my back and waited for someone to come find me. It felt like I was gone for hours. It got very cold outside and no one came. I got very angry — I can’t explain why.

Surely she knew, from the Facebook message I had sent back in December, she must know that I was the one turned her in.

She didn’t go into detail about what happened when she returned to the house, just that something violent had happened and “her roommates could not allow her to stay” that night. So I gave her tea and my couch for comfort. I couldn’t envision what she had done, certainly nothing that bad.

Now that I was her enemy, I expected a confrontation. She would stop me in the hallway, demand why I would do this to her. I imagined myself with a black eye. In office hours, I explained this concern to my advisor and she looked at me baffled, nearly giggling. “What? No, I don’t think Kelsey’s going to hurt you!?” Of course, the Kelsey I knew wouldn’t harm me, of course. But I didn’t really know her to begin with, did I? I made John walk with me to class, shielding myself with his tallness and muscle. Yet despite my precautions, Kelsey said and did nothing to me, only sat there, limp and sullen, in a daze.

* * *

Here, it is October in Indiana, the sky all gloom and pearly. The maples are looking especially autumnal, leaves blustering over the road. I am in a coffee shop, blogging about my poetry — publication news, trends I’m noticing in my work. A spike in my stats, my blog has gotten twenty-four views today — unusually high. The attention makes me flattered and uneasy at the same time. I change my settings, turn the site to “private.”

Suppose someone finds my blog and plagiarizes my writing?

Suppose I Google my own work and discover it in a magazine under another name? Suppose Kelsey is the one looking at my words?

Suppose she seeks revenge on me by stealing them?

Suppose she tweaks the poems, actually makes the writing better?

* * *

Yes, she stayed on like an old bruise that lingers. And worst of all, she proved herself to be capable of writing decent poetry (seemingly) without plagiarizing. Each week, after she passed her poem around the seminar table, I would go home, pull up a chair at my desk, and immediately start typing lines into Google. I refused to be fooled again, yet I found nothing. The poems, while they lacked the power that used to grip me, they were still beautiful and striking:

a blouse fell

from the sky

and i unstitched

the stitches

sometimes i nightmare

i turn everything off

every switch inside

and you, how you always

roll your eyes at me.

A flush of envy: how is she still able to write like this? I thought I had ruined her prospects at becoming a poet, ruined with that F on her transcript. But the girl could still write and write well. I no longer wanted her in my field, not one bit. Kelsey, the imposter, nemesis, a threat.

* * *

The moment of meeting. I sit next to her during orientation. She immediately sticks out her hand. “Hello, I’m Kelsey. I look forward to working with you.” So formal, maybe too formal? Artificial even? At a party later in the week, at her house: ginger beer, lentil soup, a record spinning, dim rooms and candle wax, so many faces to learn.

“You’re here!” Kelsey makes her way past bodies, a drink in hand. “I have a gift for you!” Following her to the bedroom and she gathers a bundle of chapbooks — paper that feels so good in your hands, saddle-stitch edge, stamped cover. I had never seen a chapbook in my life.

“You made these?” I ask, in awe, slightly tipsy. “These are for me?” How wonderful. I read them all that night before bed, keep them in my nightstand. Kelsey, the idol, the coolest girl I know, girl who knows so much more than I.

* * *

An acceptance letter from last week:

Thanks so much for sending us your poems! We would like to publish them!

Would you let us know if the poems are still available, and if so, send us a bio? Feel free to include links to where your work can be found online!

I browse through the archives of this magazine, a publication I have long admired. Feeling pleased with myself, I envision my own name printed here. Instead, her name arises — Kelsey in a back issue from the previous winter. Reading the poems, poems I knew from our classes together, I feel disgust rising in my belly. I consider sending an email back to the magazine: Did you know that you published the work of a plagiarist? I know I won’t actually do it, but the thought gives me satisfaction. Why do I still want to punish her? Haven’t I done enough?

* * *

Kelsey, reading a poem at the microphone, she growls and whispers, each word fully embodied, she is visceral. Kelsey, our birthdays a week apart. Kelsey in all black, Kelsey alone on the walk home. Why did she do it? I Google “plagiarism” and “poetry” together, just to see what would come up.

I consider sending an email back to the magazine: Did you know that you published the work of a plagiarist?

One of the first results is an essay, “Word Theft” by Ruth Graham, on the Poetry Foundation website. Graham notes recent cases of plagiarism in the poetry world — where poets such as Christian Ward, CJ Allen, Andrew Slattery were accused of stealing from newer poets as well as big names like Sylvia Plath and Emily Dickinson. These were cases where the plagiarists defended their work as “creative appropriation,” where repurposing was an “essential part” of their processes. Graham acknowledges that, of course, “writing is a dance that involves imitation, inspiration, and originality.” However, while “approaches to borrowing and attribution have shifted over time,” Graham asserts ultimately that “wholesale copying has never been kosher.” She also considers the question of why plagiarism occurs to begin with: “There’s never a satisfying answer, but there are at least lots of guesses, often somewhat at odds with each other: laziness or panic, narcissism or low self-esteem, ambition or deliberate self-sabotage.” Which was it? Which one, which one? Maybe all, maybe none?

In my search results, another essay: “Poetry Has A Plagiarism Problem” by Katy Evans-Bush, in which she questions why poets in particular would plagiarize, since with a career in poetry, “you’re not going to get famous, and you’re really not going to get rich.” Where is the gain when the stealing won’t pay off? Evans-Bush claims that, perhaps, plagiarism is really an issue of identity. When plagiarists present work that is not theirs, they are, essentially, not representing themselves. A disassociation, a splicing of the self. The girl I knew loved poetry, devoted her life to the practice of it, she wanted to write books and perform all over the country. She would never tarnish that love for anything.

* * *

Another poem of mine is accepted for publication, and upon acceptance, I suddenly recall: I wrote this poem in response to another, didn’t I? Which poem was that? What did I mimic exactly? I remember feeling stuck when I sat down to write it. Sometimes, I turn to an online text generator that offers scraps of poems, a starting place for writers. I imitated the anaphora, yes that was it, but how closely did I imitate? The content is totally different, but is the structure too similar? Maybe I could still change it? In a panic, I return to the text generator, search the archives for that poem, search for almost an hour, but no luck. My poem is published. I feel proud and I feel paranoid, half-expecting an angry email in my inbox, an accusation, a finger pointing my way: false false false.

* * *

This time of year, I always manage to become ill, late in the fall, when the night comes on early, smelling of cold and woodsmoke and spice, just on the hinge of snow. This time of year, I fall into illness and have trouble getting out. Last night, a fever dream:

I am sitting in a rocking chair, in a sequined dress, surrounded by every person I’ve been estranged from. They are waltzing around me and though we don’t speak directly to each other, I can tell they are glad and glad that I’m here, in my good dress, at the center of the room. The past is behind us, they seem to say, with their cocktails raised. And there she is, in dark velvet and warmth, a sincere laughter.

In the morning, I half-believe this really happened, I check my phone — her number still erased. There has been no forgiveness in the night. I go to her Instagram, I look on from afar, just to see how she’s doing. A childhood photo — Kelsey in buck-teeth, elfish nose and ears. A photo of her boyfriend, a trip to Kentucky. Photo of a dead monarch butterfly, wings orange and tattered on the sidewalk. Kelsey’s caption: “same here.” I tuck the phone under my pillow. I take medicine, make my tongue sour with cough drops.

* * *

Our workshop leader theorized that Kelsey had been stealing for a while, maybe all the way back to her application for the program. We tried looking for traces in her earlier work, from the previous semesters, but no dice. It’s possible she was lifting from chapbooks, from small presses, hand-stitched and unique items, poems not readily found online. I won’t probably ever know for sure — that bridge is burnt to a crisp.

Our workshop leader theorized that Kelsey had been stealing for a while, maybe all the way back to her application for the program.

And I still ask: why? Was Kelsey “stressed out?” Could she not “cope” with her classes, did she feel “intimidated” and that’s why she resorted to stealing words? No, that’s not right. In fact, she told me often how ineffective she found workshop. She was just waiting to finish her degree and be done with that place. She said these things to me on her back porch, as we sipped rum & cokes, talking gossip, talking MFA applications and what we were reading, all semester long. I saw what she meant — I couldn’t agree more. Kelsey was arguably the strongest poet in our bunch — her writing sharp and vibrant, that fierce sense of self. Perhaps her plagiarism was an act of rebellion, a “screw-you” to the program and that tiny Midwestern town. Maybe she wanted to see what she could get away with, to see how thirsty we were for her talent, how adoration made us oblivious.

* * *

She’s there now, finishing her last semester, serving out her punishment, in that place she scorned and so looked forward to leaving. In this sense, perhaps, the punishment was fitting — she could not get out, was forced to linger. Perhaps, now, this is the closest I will ever be to her. I live two hours away and there are days when I long to see her and days when I am terrified, imagining if she showed up here. Kelsey with her scratches from the wood, Kelsey in a fever dream, Kelsey at my doorstep with a peace offering, a notebook with two hands clasped in friendship, Kelsey with her spooky violins.

* * *

A July afternoon, a house where she lives. Before the book, blue with a soft cover, a woman’s face veiled. Before the ah ha moment, the email. Before, when Kelsey was a girl asleep on my couch, girl with blue hair, gray hair, black hair, always thoughtful, bold, cool as hell.

She is gone for the weekend, she asked me to come check on the house, left me with the key and a tight hug. Her roommates are home for the summer, so it’s just me, echoing as I step into the foyer. I feed the cat, I test the locks, I wander upstairs to Kelsey’s bedroom.

Although I know the room is vacant, I knock on the door anyway, a habit. Inside, a maple leaf pinned to the wall, a lighter, a photo of Kelsey with hibiscus in her hair, also records and notebooks, chapbooks in messy stacks, a writing desk, an old bouquet. I open her closet — there’s velvet and the Doc Martens, thrift-store sweaters, leggings, party dresses. I run my hands over the clothes — mmmm pretty.

A creak in the room, a rattle at the window glass. I turn my gaze to the mirror, full-length and speckled. I watch myself, being where I shouldn’t. It is electric, to be in her presence, girl that haunts, girl I want to become, to imitate, to steal from her — a little magic for my keeping.