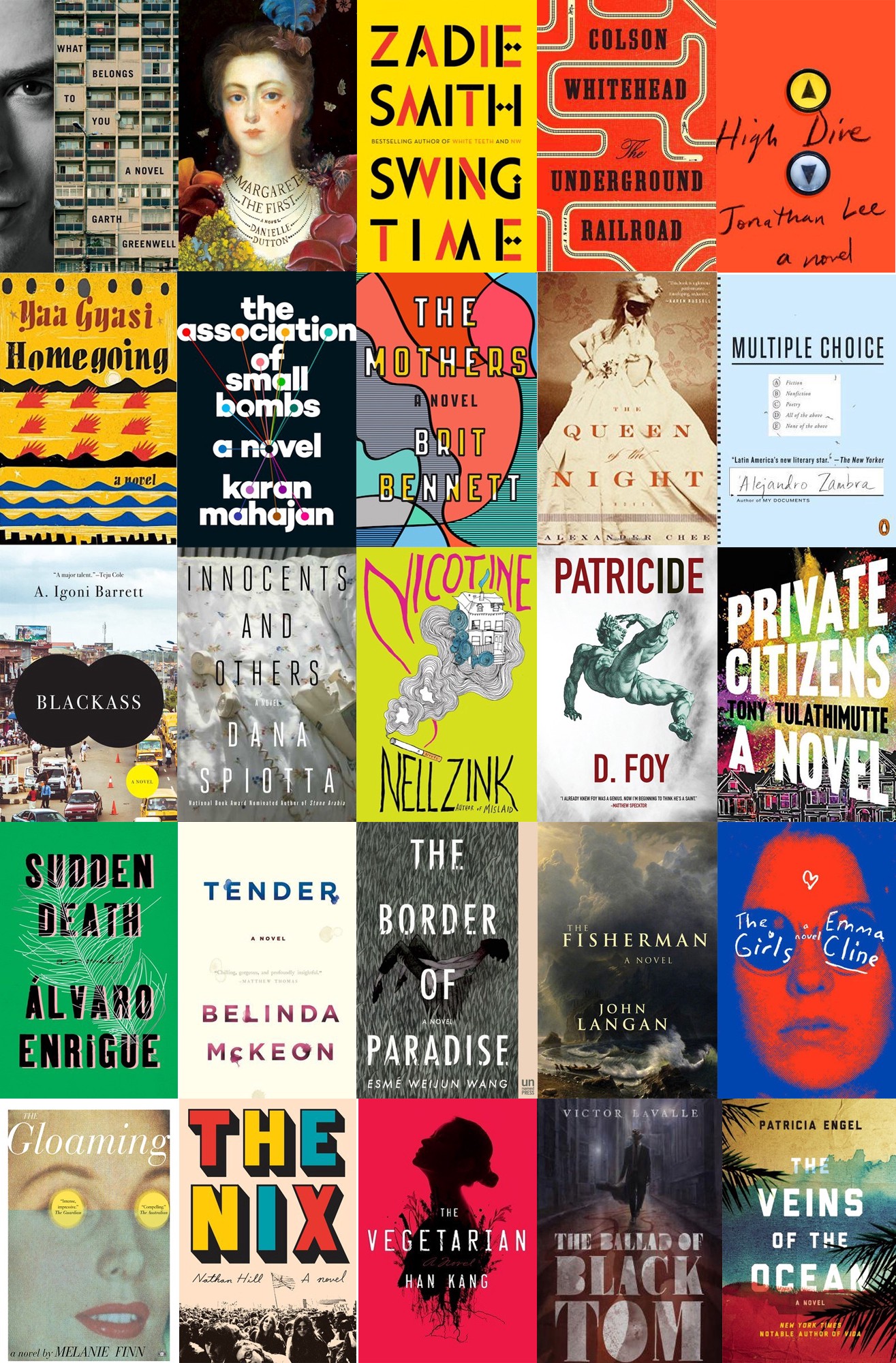

Reading Lists

Electric Literature’s 25 Best Novels of 2016

The 2016 novels that every fiction lover should read

Each year, Electric Literature polls our staff and regular contributors to pick our favorite books of the year. Whichever books get the most votes make the final list. Here are our 25 favorite novels of 2016. They include famous names and major prize winners alongside debut novelists and small press gems you might have missed. Check them out at an independent bookstore near you.

(We excluded books from staff members from the list, but we encourage you to check out Pull Me Under by Kelly Luce and Falter Kingdom by Michael J. Seidlinger.)

You can read the list of our 25 favorite short story collections from 2016 here.

What Belongs to You by Garth Greenwell

Like a Tibetan throat singer, Greenwell performs the uncanny feat of sustaining two notes in one breath. Frank depictions of sex, of venereal disease, and of rotting infrastructure lend his prose a certain stench, and keep us grounded in a post-Soviet landscape with all of its earthiness and grit. But Greenwell’s tone retains a measure of delicacy: his sentences are formal and refined, often carrying the narrative into the celestial. From one angle the book looks like a long act of solipsism, yet from the other side the book is outward-looking, even journalistic. Greenwell documents the texture of contemporary life in Bulgaria with care, and the American reader will exit the novel familiar with the country’s language and its customs.

— Laura Preston in the introduction to our interview with Greenwell. You can also read our review of What Belongs to You by Ilana Masad.

Margaret the First by Danielle Dutton

Yes, she may not have effected any radical change during her own life, but this same account does movingly relate that she was buried in Westminster Abbey, where her dedication reads, “This Duchess was a wise, witty and learned lady, which her many books do well testify.” This reveals that she managed to win over at least some admirers before her death, and that Stuart England immortalized her as an example and a role model to the generations of female writers that followed her. Thanks to Margaret the First and Danielle Dutton’s elegance with words, this may continue for many more generations to come.

— Simon Chandler in our review of Margaret the First

Swing Time by Zadie Smith

Swing Time by Zadie Smith is a magnificent, mature novel, but one that reads differently than the others previous books (which have all been incredible, each in its own way). The most noticeable thing about Swing Time, at least for a longtime reader of Smith’s work, is how much of it defies the old writing workshop adage — it tells as often as, if not more than, it shows. Paragraphs can last up to a page in length, the narration is first person, and there is a Jamesian quality to some of the sentences that is unexpected for Smith, who is an excellent wordsmith and always has been but who has tended to give her characters voice through their words more often than through their internal narration. All of which is to say that Swing Time is surprising — not that it is anything less than excellent.

— Ilana Masad in our review of Swing Time

The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead

Slavery may have been abolished in the United States in 1865, but that doesn’t mean its effects still don’t ripple throughout the country to this very day. This, at least, is the idea Colson Whitehead deftly unpacks in his harrowing sixth novel, The Underground Railroad. The New York writer sends the book’s fifteen-year-old protagonist, Cora, on a clandestine journey from the south to the north of America in search of a barely imaginable freedom, and in so doing he captivatingly depicts how the repercussions of a life in bondage can haunt and constrain people even when they’ve escaped their shackles. Yet more universally, the novel delves deeper into its brutal world by showing how the institution of slavery wasn’t simply a means of subjugating the African-American population, but also a subtle, systematic means of keeping the whole of American society in check as well.

— Simon Chandler in our review of The Underground Railroad. You can also read our interview with Colson Whitehead.

High Dive by Jonathan Lee

Though the inevitable bombing at the end of the book creates a sense of dramatic irony and dread for the reader, we see Lee’s characters distracted by their own existential crises: they go about their lives as any of us would before a tragedy, selfishly worrying about their futures, worrying about the past they can’t relive, and worrying about how to fit in when they are not sure what they have to offer. Lee’s High Dive is suspenseful, expertly paced, and an excellent read.

— Heather Scott Partington in our review of High Dive. You can also read our interview with Jonathan Lee and an excerpt of the novel in Recommended Reading.

Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi

Originally from Ghana, Yaa Gyasi was recently honored as one of the National Book Awards 5 Under 35 authors of 2016. Her debut novel Homegoing, follows the vastly different trajectories of two half sisters born in disputed Fante and Ashanti lands in the mid-1700s. One sister, Effia, is married off to a British governor and lives a life of subsequent luxury. The other sister, Esi, is taken captive as a laborer in the dungeons of Effia’s palace, and is eventually sold into the slave trade. Isabel Wilkerson of the New York Times writes: “The narrative unfolds through self-contained stories, some like fables, others nightmares, that shift between the family lines in West Africa and America, each new protagonist a limb of the disrupted family tree. Characters reappear in dreams or retellings as the action moves from the Cape Coast to Kumasi to Baltimore to Harlem.” The best-selling novel is a must-read if you haven’t gotten your hands on it already.

The Association of Small Bombs by Karan Mahajan

In Mahajan’s book, an intelligent man associated with a separatist movement plants a bomb in a Delhi market. The explosion kills two boys out to pick up a television from a repairman, but spares their friend, who moves forward in a life marked with injury. As bombs go, this is a small one, “a bomb of small consequences.”

The truth, of course, is that there is no bomb that does not have vast consequences. The explosion profoundly changes the parents of the two boys killed, spurring their participation in political life. The survivor grapples with religion. Remarkably, we observe the inner lives of a bomb-maker and an idealist drawn to terrorism.

— Megha Majumdar in the introduction to our interview with Karan Mahajan. You can also read our review of The Association of Small Bombs and an excerpt in Recommended Reading.

The Mothers by Brit Bennett

At its core, The Mothers is a novel about choice. Some choices are uncontrollable and impulsive, while others are pragmatic. Nadia Turner chooses to leave town for college and navigate her potential outside of the small community where she grew up. As Aubrey puts it, “Anywhere [Nadia] wants to be, she goes.” Aubrey chooses to stay and build her life in Oceanside. She hopes to fall in love, settle down, and start a family. The girls build different paths, but the end goal is the same: to lead happier lives than their mothers. This is where Bennett nails the paradox modern women face: the freedom of choice and the anxiety that comes with that responsibility — that people will still judge your choices.

— Fredddie Moore in our review of The Mothers. You can also read our interview with Brit Bennett and an excerpt of the novel in Recommended Reading.

The Queen of the Night by Alexander Chee

The urgency with which Chee has Liliet telling her tales, while continually creating a bait and switch narrative in which she yanks away knowledge at crucial moments only to come back to them later, keeps the reader off balance, racing through the pages without any possibility of stopping for fear of falling flat. It is that kind of novel, the kind one devours in a weekend or stays up too late reading. It’s the kind of novel one walks around reading, despite its size and heft (a fact I hope Chee, a confessed reader-walker himself, will appreciate). The Queen of the Night deserves the attention she is getting, and I plan on continuing to sing her praises.

— Ilana Masad in our review of The Queen of the Night

Multiple Choice by Alejandro Zambra

Chilean author Alejandro Zambra has been steadily putting out some of the best short novels around in recent years. His latest, Multiple Choice, is a beautiful and moving volume with a high concept: it’s written in the form of the Chilean Academic Aptitude Test. It doesn’t seem like this should work for a novel, but Zambra somehow turns multiple choice quizzes into moving meditations on family, history, sadness, and literature. Multiple Choice shows that inventive, experimental fiction can still be filled with emotion and heart.

— Lincoln Michel, Editor-in-Chief of Electric Literature. You can also read our lost interview with Alejandro Zambra.

Blackass by A. Igoni Barrett

In Blackass, no character is free from the engagement of escaping their prescribed lives. Some characters have more surreal exit strategies than others. On the morning of a crucial job interview, Furo Wariboko wakes up to find that he is no longer a black Nigerian. He’s confronted with a white body that alienates himself from himself, his family, and pretty much everyone he encounters. No one knows what to make of an oyibo, Nigerian slang for a white person, who speaks and acts with the fluency of a native black Nigerian. […] Barrett’s frenetic plot and pacing takes his characters to uncomfortable places that seem unbelievable and yet, in the moment of this novel, feel entirely plausible.

— Lauren LeBlac in the introduction to our excerpt of Blackass in Recommended Reading

Innocents and Others by Dana Spiotta

The seductive promises of the telephone, the possibilities of films imagined, but not yet made, the way a rough demo of a song extends the relationship between musician and fan from fling to full-blown love affair — these are just some of the obsessions that preoccupy Dana Spiotta’s characters, firmly situating her novels in art and the everyday. Innocents and Others, Spiotta’s recently published fourth novel, is about the possibilities of narrative, and the impossibility of controlling the reception of any narrative, whether they are the stories you tell about yourself or others.

— Adalena Kavanagh in our interview with Dana Spiotta

Nicotine by Nell Zink

Nell Zink is back with her third novel Nicotine, a wry social commentary in which a Jersey City squat is coopted by a nefarious businessman. The squatters are forced to scatter, and rooms that were built from scavenged material are transformed into state of the art yoga and puppet making studios. The kitchen where residents prepared meals foraged from dumpsters is converted to a café with expensive drinks. In this darkly comedic feud between anarchists and capitalists, Zink lays bare how the aesthetics of idealism are appropriated by corporate opportunists and subsequently fed to an unwitting and unquestioning public. As the title suggests, this novel is both addictive and jolting before leaving a final harsh, corrosive taste.

— Liz von Klemperer in our review of Nicotine

Patricide by D. Foy

D. Foy’s Patricide, his second novel, is an unusual hybrid that pushes against the edges of literary fiction with the unfiltered violence, frustration, and angst typically found in noir novels but does so with an elegance and lyricism that echo giants like Cormac McCarthy and Walt Whitman. Equal parts devastating coming-of-age (and beyond) narrative and philosophical examination of fatherhood, Patricide is, more than a novel about a man who survives a devastating, abusive childhood, a text that explores both identity construction/deconstruction/reconstruction cycles and the generational recurrence of aberrant behavioral patterns and falsehoods.

— Gabino Iglesias in our review of Patricide. You can also read our interview with D. Foy.

Private Citizens by Tony Tulathimutte

Tony Tulathimutte’s debut novel, Private Citizens (William Morrow, 2016), follows four recent college graduates as they flail, flail again, and flail better. The book is an uncanny mirror. If you’re an aspiring writer, a do-gooder, an Interneteer, or a human with a reasonable amount of despair, you might flush with recognition.

— David Busis in the introduction to our interview with Tony Tulathimutte

Sudden Death by Álvaro Enrigue

It is a suitably strange, light-footed but historically weighty construction that centers around a fake tennis match between the painter Caravaggio and the poet Francisco de Quevedo. From this central conceit, Enrigue expands the frame to take in the immense canvas of Counter-Reformation Europe and Cortés’s New World. It is a brilliant synthesis of art, history, religion, power politics, and — yes — tennis, a complex study of our world via the world that gave birth to modernity. It is much like an American postmodern book, except it is very different from, say, a Pynchon or a DeLillo since it is carried along by Álvaro’s very Mexican wit and sensibility, as well as his own intuitive logic. His books are at once morbid and celebratory, somber and slapstick, historic and very much about the present. Precisely how Álvaro reconciles these opposites indicates his unique contribution to our world of letters.

— Scott Esposito in the introduction to our interview with Alvaro Enrigue. You can also read our review of Sudden Death.

Tender by Belinda McKeon

Her new novel, Tender (Lee Bourdeaux Books, 2016), hailed by The Guardian as “richly nuanced and utterly absorbing,” tells the story of shy college freshman Catherine and flamboyant photographer-in-training James, two nineteen-year-old rural exiles in Dublin as they navigate the increasingly intense nature of their co-dependent relationship. It’s a beautiful, claustrophobic evocation of friendship, longing, and the obsessive power of first love.

— Dan Sheehan in the introduction to our interview with Belinda McKeon

The Border of Paradise by Esmé Weijun Wang

Esmé Weijun Wang’s debut novel is a multigenerational epic that begins in postwar New York. Touching on mental health, family drama, and human tragedy, The Border of Paradise is a moving and beautiful book. The New York Times said the novel “is shaped by darkness and the kind of delicious story that makes for missed train stops and bedtimes, keeping a reader up late for just one more page of dynamic character-bouncing perspective.”

The Fisherman by John Langan

Langan’s fiction often involves stories told within stories, and that’s also true of his new novel The Fisherman (Word Horde, 2016). […] Set in the Hudson River Valley, it’s about the friendship between two widowers and a trip they make to a mysterious location, and the ominous history that they uncover along the way. There’s a lot to admire in it, from its depictions of grief and loss to the story it tells about the slow economic decline of the region in which it is set, over the course of the last decades of the twentieth century. Oh, and there are monsters, too–some of the most unsettling imagery I’ve encountered in fiction in a long time, and a strain of cosmic horror that takes the style in a memorably different direction.

— Tobias Carroll in the introduction to our interview with John Langan

The Girls by Emma Cline

What makes The Girls different is how muted the violence is: here, the monster is not women but expectation. The girls ultimately succumb to being who they are wanted to be.

For Cline, though, women are not to be blamed for weakness or for seeking to please. The red hands instead belong to society itself — a churning, unnamed force that pushes everyone toward their end even as the novel draws inevitably closer to the only finale it could have: murder.

— Jeva Lange in our review of The Girls

The Gloaming by Melanie Finn

Melanie Finn’s second novel, The Gloaming, opens with the end of a marriage. The scene is a mutual friend’s home outside of Geneva, and the catalyst for the collapse is a young woman, Elise, who the novel’s narrator, Pilgrim, sees approach her husband while the three are on a group walk. Pilgrim continues on ahead of the pair, and she looks back occasionally to watch them chat. Her husband, Tom, leans toward Elise; Elise covers her face to laugh. They flirt in a “breathless air,” caught in a moment where everything seems “amplified, impulsive,” and yet Pilgrim never interrupts their encounter. It’s almost as if she knows a chapter of her life is coming to a close. […] This is a pure example of a literary page-turner, one that begins with an ending and ends with a new beginning, written by a very smart author.

— Benjamin Woodard in our review of The Gloaming

The Nix by Nathan Hill

Nathan Hill’s debut novel follows professor and failed writer Samuel Andresen-Anderson whose missing mother suddenly comes back into his life as she faces charges over political activism. It is a big book filled with big ideas about American life. The Washington Post said “Hill is a sharp social observer, hyper-alert to the absurdities of modern life” and People said it was “as good as the best Michael Chabon or Jonathan Franzen.”

The Vegetarian by Han Kang

Flesh permeates the work of the novelist Han Kang. Her novel, The Vegetarian, obsesses over it. Unsurprising considering the bulk of the story follows Yeong-hye, who, after a disturbing and bloody dream, becomes a vegetarian. Although a strong Buddhist tradition exists on the peninsula, for most, meat is an essential aspect of Korean cuisine and culture, and reflects Korea’s status as a growing economic power. […] Discomfort is what Han Kang does best. Her writing is strongest when she makes the reader linger over difficult imagery or ideas that South Koreans are reticent to broach.

— John William Walker Zeiser in an essay on Han Kang’s work

The Ballad of Black Tom by Victor LaValle

The dedication of LaValle’s book speaks volumes: “To H.P. Lovecraft, with all my conflicted feelings.” Whether The Ballad of Black Tom is approached as a straightforward tale of horror in the early 20th century or as a metafictional commentary on Lovecraft’s own storytelling choices and racism, it succeeds. It also stands as proof that the process of engaging with the conflicted feelings that the work of Lovecraft can prompt can lead to rewarding, emotionally compelling writing of its own.

— Tobias Carroll in our review of The Ballad of Black Tom. You can also read our interview with Victor LaValle.

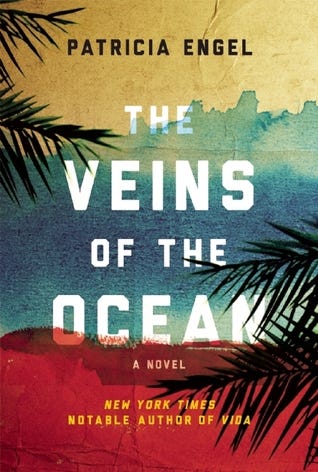

Veins of the Ocean by Patricia Engel

Patricia Engel’s new novel, Veins of the Ocean (Grove Press 2016), begins with one of the more arresting sequences I can remember. Whenever I’ve recommended the book to a friend, or a colleague, or anyone who would listen, rather than telling them what the book was about, or trying to explain why it was urgent to read now, at a time when our country seems hell bent on dehumanizing the immigrant (and first generation) communities that form its bedrock, I opened up my copy of Engel’s book and asked them to read the first page.

— Dwyer Murphy in our interview with Patricia Engel