interviews

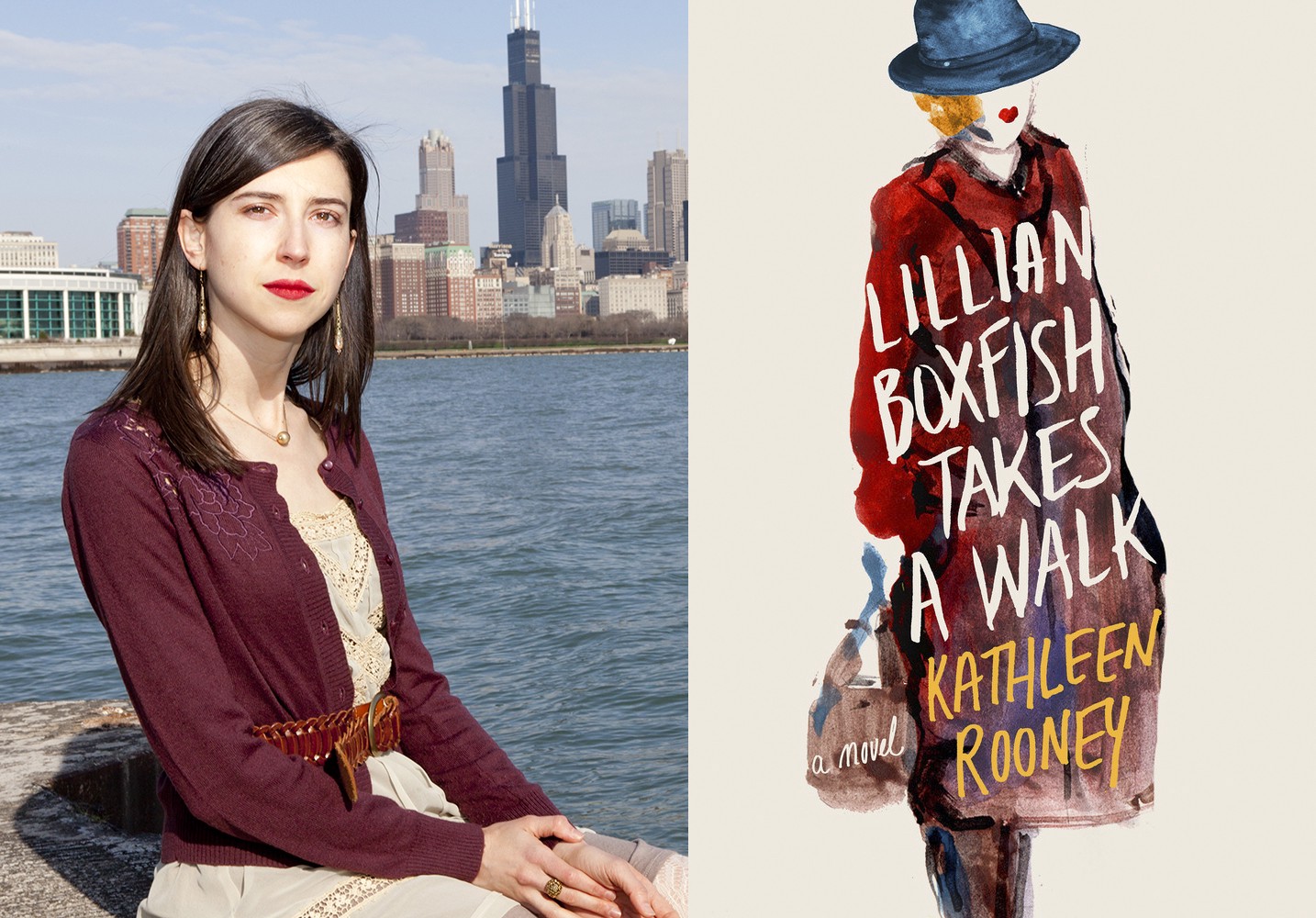

Kathleen Rooney & The Art of the Stroll

The author of ‘Lillian Boxfish Takes a Walk’ discusses New York in the 80’s, a proto-feminist in advertising and the joys of flânerie.

Kathleen Rooney’s new novel, Lillian Boxfish Takes a Walk (St. Martin’s Press) follows the life of the red-headed poet of Murray Hill. Spanning six decades, from Lillian’s illustrious career as R.H. Macy’s highest paid ad-writing woman, her life of poetry, love, and heartbreak, to the New Year’s Eve of 1984, where she takes her long, adventurous walk through Manhattan, this novel is both sprawling and personal, and in Kathleen Rooney’s hands, Lillian is nothing short of extraordinary. Via email, I had the pleasure of discussing the new book with Rooney, where we covered Lillian, the joys of research, and the Rooney’s own love of walking.

— Timothy Moore

Timothy Moore: There’s so much here that I want to talk about with Lillian Boxfish, and time, and writing, but maybe we should start with something more basic: walking. A major part of your new novel is Lillian’s journey from one end of Manhattan and back on New Year’s Eve, 1984. It’s no small task, Lillian being in her eighties during a time when New York City was seen as deteriorating and dangerous, but it becomes increasingly important for her to make this long trek. Can you discuss a bit your own views of walking? Do you find walking to be important to your development as a writer/teacher/editor/person? Maybe it’s not so basic a question after all!

Kathleen Rooney: This is a basic question in the sense that aimless yet attentive walking around an urban environment — aka flânerie or dérvive or psychogeography — is one of the basic necessities and joys of life: city walking is fundamental. An essential foundation. A starting point. I’ve been a walker ever since I was a little kid — every time I get to a new place, the first thing I want to do is to walk around it and map it in my mind with my feet. Walking means so much to me that it’s difficult to distill what I love — the physicality and rhythm, the potential for meditation, the freedom, the chance encounters with strangers — into a single response, which I suppose is why I had to write a novel about it.

Walking resembles and relates to both reading and writing to such an extent that I teach a class at DePaul (and sometimes in the Iowa Summer Writing Festival) called Drift and Dream: Writer as Urban Walker. It might seem surprising that you could teach a whole class on something as universal as walking, but I’m continually amazed at how relatively few people walk, or how walking is mistakenly seen as a chore to be minimized or an inconvenience to be avoided. I grew up in the suburbs and intuitively despised car culture — its waste, its destruction of our environment, its isolation of people into tiny, atomized units where serendipitous encounters with others are almost totally eliminated — and found myself drawn to cities and to flânerie before I even know the activity had a name. As soon as I could leave for college, I chose to move to Washington, DC and since then have lived in cities almost exclusively. I’ve lived in Chicago for almost 10 years now, and no matter how many times I walk through this city, I never get bored. Because if you’ve taken a walk once, you’ve taken it once — even if you walk down the same stretch of street a hundred times, it will be different on every single journey because the city is an organism that’s always growing, changing, dying and being reborn.

Lillian shares this admiration of cities, as well as the xenophilia that a lot of urban drifters share — not a fear of difference, but a desire to seek it out and interact with and appreciate and understand it. Normally, I’m leery of hyperbolic prescriptive claims, but I truly believe that if more people took walks through cities, the world would be a better place.

I truly believe that if more people took walks through cities, the world would be a better place.

Moore: That’s what really struck me with Lillian — her ability to seek out people, strangers really, and have patience with them, and more often than not, she connects with them. Even though, by the 1980s, her poetry is no longer in fashion, and her writing career at R.H. Macy is long over, and the city itself is drastically changing, she holds onto this personal ethos. I think the fact that she is aware of her failures and growing loneliness (she is no Pollyanna!) while holding onto what she values, makes her a more complicated character. While Lillian was inspired, in part, by the real life Margaret Fishback (who was also a poet and ad woman in the 1930’s) — I’d be interested to learn of your process with developing Lillian as a full-fledged character in her own right.

Rooney: Thanks to an invaluable tip from my high school best friend, Angela Ossar, I got to be the first non-archivist ever to work with the archives of Margaret Fishback at Duke University back in 2007. Fishback herself is an important proto-feminist figure, a pioneer of advertising and a gifted light verse author, so I’m hopeful that the novel gives readers an occasion to learn more about her. I’ve written a piece about her advertising innovations and poetry for the Poetry Foundation that you can read here. And I worked with them to get a selection of her work included in their archives here.

That said, it took me several years before I figured out what to do with the material I’d worked with in the archive on a larger scale. The key that unlocked my idea that it should end up as a novel was to give Lillian the fictional character an undying affinity for flânerie, and also to give the book a split structure, partly set starting in 1926 to chart Lillian’s stratospheric rise and eventual fall, and partly set on New Year’s Eve in 1984 as she’s on this magical — but still realistic — 10-plus-mile drift. This balance let me have the imaginative flexibility to create scenarios for Lillian to respond to, and to round her out as someone distinct from the person who inspired her. I love movies — like Adventures in Babysitting or Desperately Seeking Susan — and books — like Patrick Modiano’s In the Café of Lost Youth and Vivian Gornick’s Fierce Attachments — where the city itself stops just short of becoming a character. So in a way, getting to research so much about New York in all its various 20th century incarnations is what helped me to create the character of Lillian most of all.

Moore: This split structure really paints the drastic changes in New York’s incarnations — I wonder, what was it about 1984 New York City that worked for a setting instead of, say, 1990? Was there something about this year that struck a chord with you?

Rooney: 1984 was the year I needed because of Bernhard Goetz, aka the Subway Vigilante. On December 22, 1984, he shot and seriously wounded four black teenagers — who he claimed were muggers — on a downtown 2 train. He escaped and went into hiding for nine days before eventually turning himself in to police. You know that Billy Joel song, “We Didn’t Start the Fire” that came out in 1989? Nine-year-old dork that I was at the time, I looked up every single reference and out of all the monumental historic events listed in the lyrics, that one stunned me the most because I couldn’t imagine doing that: taking “justice” into my own hands with the intent to kill four strangers on mass transit. As an adult, I continue to be fascinated by how polarized public opinion was regarding his act at the time, with some people appalled and others hailing him as a hero. The crime rate in New York in that era was incredibly high and a lot of people despaired at how to turn it around, which meant some people inevitably thought Goetz’s approach was the right one.

Lillian, of course, finds violence repulsive. So I wanted her to simultaneously have a chance to weigh in on Goetz’s horrific act in terms of her beliefs in respect and civility, but also to show how fearless she’s resolved to be. To stay in New York from 1926 to 1984 would take quite a bit of commitment and determination, and Lillian has it.

Personally, the suburbs make me sick because they’re boring, exclusionary, homogenous, car-centric and full of suspicion of people who are different. So thematically, I wanted to show Lillian being enamored and unafraid of the unruly and heterogeneous city in a way her own son, Gian, a city kid turned city-fearer is no longer capable of. Also, at a time when a lot of her old friends are bailing for the Sun Belt, Lillian continues to be true to her first and most consistent love: New York.

Last but not least, 1984, lucky for me, worked with the age that I needed Lillian to be for the timing of the rest of the story (the Roaring 20s, the Depression, WWII, etc.) to work. She was born in 1899 (though she lies and says 1900 to not have to admit to having been born in the 19th Century), so by 1984, she’s quite old. I wanted her to be elderly enough for a walk of this distance and duration to be exceptional and impressive, but not implausible.

Moore: A lot of writer’s struggle with research and incorporating their findings. Would it be fair to say that you lie on the opposite side of that spectrum? Is there any advice you can give writers in the midst of their research?

Rooney: The research phase of any project — whether it’s fiction, nonfiction, or poetry and whether it’s something set now or in the past — is my favorite phase. Because when you’re researching, everything about the project is pure potential — it could be anything and it could be the best! Once you start translating what you’ve learned during the research phase into the book itself, of course, the potential energy becomes kinetic and the ideal that you may have held in your mind starts to emerge as a less-than-perfect real thing. That part is fun, too, but research is fascinating to me because I love reading and learning and finding inspiration in sources outside my own lived experience. I can usually tell that I’m doing research right when I get the feeling that even though I am dealing with facts, the process is also an imaginative act. Little stumbled-upon details can illuminate a character or suggest a setting or trigger a scene, and tiny bits of trivia can open out onto much bigger vistas.

As for advice, the thing about research is that a person could theoretically do it forever. It would be impossible to ever truly hit a point where you know everything there is to know about a given topic. So you have to judge when to move on from research — or at least pure research — and into the writing phase itself. Eventually, you have to let your inevitably imperfect knowledge be enough so you don’t get stalled out. You can always move back into more research after you’ve begun writing if you need more info or detail for a particular chapter or scene.

A piece of advice that I find invaluable specifically for the relationship of research to fiction comes from Janet Burroway who got it from Mary Lee Settle. In her excellent text book, Imaginative Writing, Burroway says that Settle says: “Don’t read about the period your researching, read in the period,” meaning immerse yourself in the vernacular of that era — the memoirs, the letters, the magazines, the novels, etc. This recommendation helps ensure that the fiction doesn’t become too non-fiction-y, which is to say bogged down with excessive and almost journalistic detail at the peril of plot, voice, and character.

Moore: I think that’s great advice — especially since we get such a good feel of the ads and the poetry of Lillian’s time in your novel. There’s a witty, playful quality to her writing specifically; it’s not fluff as there’s often a seriousness and intention behind her work (both in her ad writing and her poetry). Later in the novel, Lillian is viewed as an anomaly in the ad writing that she’s done — do you think Lillian’s brand of writing is a lost art in advertising? What about poetry?

Rooney: Lillian’s era was one in which magazines and newspapers included verse in virtually every edition or issue, and in which the poets who write that verse could be handsomely paid for it. That era is over, but thanks to Poems While You Wait, I can say that people are still willing to pay good money for poetry. More importantly, I can say that people still like to read and enjoy it. Whenever we set up our typewriters somewhere to do poems on demand at five dollars a pop, we almost always encounter demand from the public that exceeds our supply. I get so bored when I hear people say that poetry is dead or that nobody reads poetry. It practically seems like the main poetry critics for the New York Times Book Review, for instance, David Orr and William Logan, are contractually obligated to say in every review something along the lines of: “Nobody likes this stuff, but here’s a review of a new poetry book anyway!” It’s tiresome. So sure, light verse is arguably a lost art, but people still love, need, and want poetry, especially poetry that is, like Lillian’s (and her real-life inspiration, Margaret Fishback’s) fun but serious. A great book coming out in 2017 that I think is a perfect example of light-yet-heavy and brilliant work is Bill Knott’s I Am Flying into Myself: Selected Poems 1960–2014, edited by Tom Lux.

Lillian’s kind of snappy, rhyming ad copy is mostly a lost art, too — or maybe less lost art and more just out of fashion. But I think that someone with her attitude — attentive, observant, generous, sharp, progressive and a great watcher of people — would still be well-suited to excel in the field of advertising, except in different structures and formats.

Moore: Now that we’re reaching the end of our interview, I’m going to cheat a bit and ask you multiple questions, all wrapped in one! Now that Lillian Boxfish Takes a Walk is out in the world, can you reflect on your experience with writing this novel? Has it been different from your other work? And, finally, what will you miss most about writing Lillian?

Rooney: Multiple questions in one — nice efficiency! And retrospection! I sent this novel to my agent in August of 2015, and St. Martin’s accepted it for publication in November of that year, so the book has been written for a while, and the actual experience of writing it feels far away, especially because I’ve been working on other projects — including Magritte’s Selected Writings and another novel — since then. But when I look back on writing Lillian, I have particularly fond feelings about working so closely with the Google Map I made of her route across Manhattan, a more artistically rendered version of which is on the inside cover of the book. The fact that my protagonist, though imaginary, had such a tangible path is something that sets this book apart from anything else I’ve done. I like that anyone could take her walk in real life if they were inclined to do so, and I’m grateful to St. Martin’s for doing such a gorgeous job with the map, because maybe some people will actually take it. As for what I’ll miss most about writing Lillian, there are so many things I like about her, but I think that here I’ll say: her lifelong work ethic. She is someone who loved her work and was able to lose herself and find joy and fun in it, and that made it easier for me, when it came to writing the novel, to do the same.

About the Interviewer

Timothy Moore has been published in McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, the Chicago Reader, and Entropy. He is a Kundiman fellow. He currently lives, teaches, and sells books in Chicago.