Reading Lists

The 5 Weirdest Lawsuits About Authors Stealing Ideas

‘The Art of Fielding’ is hardly the first novel to be the subject of a possibly dubious plagiarism suit

In a lawsuit filed September 14, a former Swarthmore College baseball player named Charles Green accused Chad Harbach, author of The Art of Fielding, of stealing significant plot points from Green’s unpublished autobiographical novel, Bucky’s 9th. “The two baseball novels bear a substantial similarity that could occur only as a result of Harbach’s access to a version (or versions) of Bucky’s and his large-scale misappropriation of Green’s creative efforts,” the suit claims. Among the “uncanny” parallels cited: Both are baseball stories. Both concern, specifically, the baseball teams of Division III liberal arts colleges. Both involve a baseball prodigy coming of age, and incorporate a “Recruiter-Mentor Plot” and an “Illicit-Romance Plot.” Both feature an estrangement between a father and his adult child. Also, both have a “climactic beaning scene.”

Does this amount to plagiarism? It’s hard to say. The two novels share a number of elements, but many of these elements are also present, in, say, the Futurama episode “A Leela of Her Own.” Unlike cases of stolen language, à la Jonah Lehrer or Melania Trump, claims about stolen ideas are challenging to prove. But that doesn’t stop people from trying. Here are five other interesting, weird, or downright ridiculous claims of literary theft.

Claim: Chelsea Clinton stole Harriet Tubman

Chelsea Clinton’s children’s book She Persisted features famous historical women who, in Clinton’s words, “overcame adversity to help shape our country.” Due to that very adversity, famous historical women are in notably shorter supply than famous historical men, and while the book does feature heroines you might not have encountered in school, its slate of role models is still relatively obvious: Ruby Bridges, Sally Ride, Sonia Sotomayor, Oprah Winfrey. Still, Christopher Janes Kimberley was convinced enough that Clinton copied his idea that he sued her and her publisher, Penguin Random House, for $150,000. Kimberley had submitted a pitch for a children’s book called A Heart is the Part That Makes Boys And Girls Smart to Penguin Young Readers (directly to the president of the imprint, no less!). Instead of publishing it or responding, he said, Penguin gave the idea to Clinton. His proof? She used quotations from three of the same women that he proposed to cite in his “Quotable Questionnaire”: deep cuts Harriet Tubman, Nellie Bly, and Helen Keller. Right-wing and alt-right media salivated over the suit, but everyone else seems to have given it all the credence it deserved.

Claim: J.K. Rowling stole the word “muggle”

J.K. Rowling has been accused of idea theft, and vice versa, so many times that there’s a whole Wikipedia page for “legal disputes over the Harry Potter series.” The earliest was American writer Nancy Kathleen Stouffer, who sued Rowling for infringement in 1999, when only three of the books had been published (although it was already clear that the series was turning a handsome profit). Stouffer claimed that she’d invented the word “muggle” in her vanity-press book The Legend of Rah and the Muggles, and that another of her works featured a character named Larry Potter. This is thin enough—but the court didn’t just rule that the similarities were too vague to amount to much. It actually found that even Stouffer’s weak evidence may have been fabricated. “In connection with this litigation, Stouffer has produced booklets entitled The Legend of Rah and the Muggles that were allegedly created by [publisher] Ande in the 1980s,” says the judgment. “However, plaintiffs have submitted expert testimony indicating that the words ‘The Legend of’ and the words ‘and the Muggles,’ which appear on the title pages of these booklets, could not have been printed prior to 1991.” Ditto for the tale of Larry Potter, which the judgment describes as the story of “a once happy boy named Larry who has become sad.” Stouffer said that the ’90s provenance of the words “muggle” and “Potter” wasn’t related to the case; she attributed it to “the fact that she continued to revise the story into the 1990s.” But the court found the whole thing unconvincing. Not only was the case dismissed, but the judge fined Stouffer $50,000 for “intentional bad faith conduct.”

Claim: Stephenie Meyer stole sex on the beach

In a general sense, the Twilight saga is like every vampire novel and also every teen novel ever written. But in a more concrete sense, according to Jordan Scott, it is specifically like the vampire novel she wrote as a teen. Scott said she published excerpts from her 2006 novel The Nocturne online, where Stephenie Meyer could have (and, she alleges, did) use them as the basis for the fourth Twilight book, Breaking Dawn. Among the evidence: both books include a wedding, and a sex scene on a beach. Not only that, but both beach sex scenes involve such elements as oceans, kissing, happiness, and someone being called “beautiful”! Characters in both books also have nightmares, become pregnant, are sad when someone they love dies. The case was dismissed, but the lawsuit is worth reading, mainly because the excerpts it includes are so comprehensive that you no longer have to read The Nocturne or Breaking Dawn, if indeed you ever did.

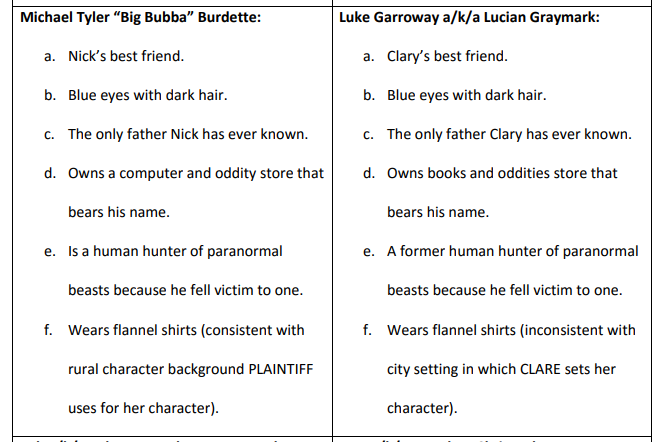

Claim: Cassandra Clare stole the urban fantasy genre

Unlike many of the plaintiffs in these cases, Sherrilyn Kenyon is herself a successful, New York Times bestselling author. The titular “darkhunters” of her Darkhunter series have supernatural powers and defend the world by slaying demons. Her suit alleges that also-bestselling author Cassandra Clare infringed on her copyright for Clare’s Mortal Instruments series, which features a similar band of supernaturally-powered demon-slayers called “shadowhunters.” The complaint includes a 15-page comparison of the two series; one character in each, for instance, is “rebellious and beautiful,” can’t cook, “seems flamboyant and loud, but is generous and tender‐hearted,” and “wears tall boots,” so I will be suing also.

There are certainly a lot of similarities, and maybe they add up to something—but as Laura Miller reported at Slate, “After the Guardian wrote about the suit, my own social media feeds filled up with writers alarmed at the notion that a litigious author seemed to be claiming ownership of some very commonplace motifs of the fantasy genre.” Some of the similarities, as described in the suit, seem eerie; others are simply tropes. (And some are reaches. One comparison lists only two traits: “jet black hair spiked with color” and “bisexual.” Pretty sure the idea of queer kids dyeing their hair is not copyrighted.) Is it possible that two authors independently came up with the idea of “mortal or normal objects…including without limitation a cup, a sword, and a mirror, each imbued with magical properties to help battle evil and protect mankind”? Considering the genre, it’s almost impossible that they wouldn’t. And “Both works take place in an urban world that is not what it seems” sounds less like an accusation and more like a definition. But are the rest of the parallels enough to support Kenyon’s claim? We’ll find out when the case goes to trial in 2018.

Claim: Dan Brown stole the secret of the Holy Grail

Like J.K. Rowling, renowned author Dan Brown has weathered several lawsuits. The most interesting, though, was the one brought by Michael Baigent and Richard Leigh, authors of Holy Blood, Holy Grail. The case itself wasn’t all that exciting; the judge eventually decreed that historical research, however broadly interpreted, is fair game as a substrate for fiction. In fact, Brown himself openly acknowledged Baigent and Leigh’s book, which argues that the “Holy Grail” refers to the bloodline of Jesus’ descendants after he married Mary Magdalene, as an influence. (Many other novels, including Foucault’s Pendulum and the comic book Preacher, have name-checked or been inspired by the book as well.) The really interesting part about this suit didn’t come to light until a few weeks later, when lawyer and Guardian writer Dan Tench noticed that the judgment was scattered with seemingly-random italicized letters. “I did not seriously consider that the judge could have implanted a hidden message in the judgment,” Tench wrote. “High court judges simply do not do such things.” But at the urging of judge Peter Smith, Tench took a closer look. The first ten italicized letters spelled out SMITHYCODE, and a Fibonnaci-based formula applied to the rest spelled out “JACKIEFISHERWHOAREYOUDREADNOUGHT.” “This must be taken as a doubtless riposte by the judge, who lists the study of the early 20th century admiral, Jackie Fisher, as a main interest,” wrote Tench. “When asked who was Jackie Fisher, how many times must he have answered that Admiral Fisher conceived of the great battleship HMS Dreadnought?” Of course. Much easier to embed that answer in a code in a judgment about a book about the Holy Grail.