Craft

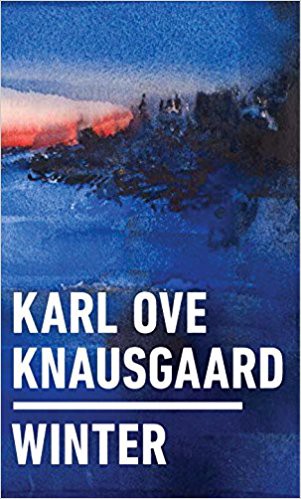

Karl Ove Knausgaard On Writing Habits, Conversation, and Why They’re Both Kind of Dumb

Two excerpts from his new book ‘Winter’

Karl Ove Knausgaard’s book Winter, which will be published on January 23, is the second in a series of four seasonal books, in which the Norwegian memoirist collects short essays, meditations, and letters to his as-yet-unborn daughter. The subject matter in Winter ranges from toothbrushes to Norse deities to Santa Claus to the moon, but of course it circles back many times to words and writing—Knausgaard’s passion and profession. In the following excerpts, Knausgaard talks about his writing habits—not what time he starts work every day, mind you, but what a habit actually is and where our need for them comes from—and discusses the difficulty of interpreting a conversation when all you have to go on is words.

Habits

For some reason writers are often asked about their routines and habits, such as what time they get up to write, whether they write by hand or on a computer, whether there is something they can’t do without while they are writing. What it is about the writer’s role in particular that awakens public interest in their daily lives is hard to say, but there must be something, since this doesn’t happen with other comparable professions. Maybe it has to do with the fact that everyone can write and read while at the same time there is something exalted about the role of the writer, and that this gap, which seems incomprehensible, must be bridged. Or it may have to do with the fact that writing is voluntary, and that a person who writes can always refrain from doing so, which is unthinkable in the case of an employee, and therefore obscure or tempting. When I was young I read interviews with writers with avid interest. I wasn’t looking for a method, I don’t think; what I wanted to find out was rather what it took. A pattern, a common denominator: what makes a writer a writer? Now I know that all writers are amateurs, and that perhaps the only thing they have in common is that they don’t know how a novel, a short story or a poem should be written. This fundamental uncertainty creates the need for habits, which are nothing other than a framework, scaffolding around the unpredictable. Children need the same thing, something has to be repeated in their lives, and this can’t be something inner, it has to involve external reality, they must know in advance at least some of what is happening around them. That repetition is not innate to us, the way it is to most other beings, but has to be created and maintained by acts of will, is perhaps the main difference between animals and humans. Animals such as dogs who are taken from their natural surroundings and introduced into new settings have nothing to parry unpredictability with, and get caught up in insane repetitions, tics and other compulsive acts. If it is great enough, children react to unpredictability in similar ways. Anxiety, aggression, antisocial behavior. Dante held that we can never understand the actions or feelings of others by reference to our own, as the baser animals can, and that this is why God gave us language. In other words, to make the differences visible, so that they become predictable and functional and enable social relations. But if differences are repeated, they become similarities, that is their own opposite. This makes language treacherous, it serves two masters, and that and no other is the reason literature exists. And that is why only people who are unable to write are able to write it. For if habit is allowed into literature and not kept outside, it is no longer literature, merely still more scaffolding around life.

Conversation

A great deal of interpersonal communication takes place outside language. If one records a conversation and writes down what was said, it becomes clear how important context is to what is spoken, which in itself is incomplete, characterized by hesitation, lacunae and allusions, and not seldom borders on the meaningless. This is so not only because we employ our whole body to complement our words when we speak, or because in a conversation we are attentive to everything the other bodies convey soundlessly, but because the conversation itself is usually about something quite other than what the words express. A conversation about something that has intrinsic value, where what is said is both important and interesting in itself, occurs so rarely that it clearly isn’t the main objective of human intercourse. “It sure is raining outside” is a fairly common statement, and clearly perfectly meaningless since everyone who hears it can see the rain for themselves. “It certainly is” might be the equally meaningless reply. Then there might be a pause before the next statement is uttered. “They say it’ll improve a little tomorrow.” What this conversation is really about is impossible to determine until we know where and when it took place, who took part in it and what kind of relationship there was between them. If it occurs in a large house the morning after a party, most guests having left to visit the small coastal town nearby, between two people who have chosen to stay and take it easy, maybe read a little, and who don’t know each other but are now in the same room, and he is looking out of the window at the shiny wet green lawn and the heavy grey sky, where dense streaks of rain hang like a gently wavering curtain, and she, who was in a chair reading until he entered the room, but has now risen, walked over to the large tiled stove and put a couple of logs into it, and who, as he says that tomorrow’s forecast is better, tears off a piece of newspaper and pushes it in beneath the logs, then the exchange of words about the rain might be a way of establishing a shared space, of affirming that though they don’t really know each other, they aren’t strangers either, since they have common friends and are now here together. In that case they will each soon go their own way, and before long both the conversation and the situation will be permanently forgotten. But if their eyes met several times during the party the evening before, without any words being exchanged, just these crossed glances, then the conversation in the living room, where she is now striking a match against the rough edge of the big matchbox, and he turns to look at her, and she feels his gaze even though she is crouching with her back to him and poking the lit match into the paper, which immediately catches fire and starts to burn with a thin flame, then it might mean something very different. When she tosses the still-lit match into the fire and stands up, unconsciously rubbing her palms up and down along her thighs as she meets his gaze, and he smiles quietly as he cups the hand that is hanging at his side, and she says, “But it’s good for the farmers at least,” it is turning into a conversation neither of them wants to end, because they are in the process of finding each other through it, and if they do, then perhaps her line “But it’s good for the farmers at least” will later become a classic in their personal mythology, when the first time they met has been turned into a story they remind each other and perhaps also the children of once in a while, to strengthen the bonds that ineluctably weaken over time, and conversations that on paper look flat finally carry no other charge, expressing only indifference.