Read More Women

Lydia Kiesling’s Favorite Books That Aren’t By Men

Win all five, and a copy of her new novel “The Golden State”

Plenty of writers, including Lydia Kiesling, live in San Francisco. Plenty of books are set in San Francisco too. But Kiesling’s debut novel The Golden State follows its central character—Daphne, a young mother separated from her immigrant husband—out of the city and into the desert areas of California, where writers and their plots don’t often go. Which is not to say the land is lacking for stories; as Kiesling’s novel makes clear, it’s pulsing with them.

Read More Women is Electric Literature’s series, presented in collaboration with MCD Books, in which we feature prominent authors, of any gender, recommending their favorite books by women and non-binary writers. Twice a month, you’ll hear about the five non-male authors who most delight, inspire, and influence your favorite writers. Kiesling, the editor of The Millions, has chosen books that are spiritually akin to The Golden State—dealing with motherhood and women’s experience, or set in California—and others that run far afield, like a fictionalized biography of Alexander the Great. That’s a nice reminder that books by women can go anywhere, even into the minds of men.

You can win all five of Lydia Kiesling’s picks, plus a copy of The Golden State and one of our Read More Women tote bags to haul them all around in! Just make sure you’re following MCD on Twitter, and tweet a link to this article with the hashtag #ReadMoreWomen. We’ll randomly pick a winner on September 10.

Fire from Heaven by Mary Renault

I bought The Persian Boy, the sequel to this book, when I was in a Greek bookstore years ago; I had no idea what it was about, but it was one of a handful of books in English and I bought it because I was desperate for something to read. It turned out to be so riveting that I went back to the same bookstore and spent many of my then-weak dollars to get the others in the series, a fictionalized account of the life of Alexander the Great written using a combination of deep textual knowledge and lovely fluid prose. I put the textual knowledge part first because that’s how the book is often lauded, as having a perfect grasp of the original source material, but I had no idea when I was reading and I didn’t care — I was spellbound by the way she made all of the characters live on the page. (“The child was wakened by the knotting of the snake’s coils about his waist.” What an opening!) (But! It is satisfying to know she also had the chops to satisfy history buffs.) Renault had an unusual life for her time — she went to Oxford, she worked as a nurse, she had a lifelong romantic relationship with another woman (she evidently wrote about non-historical queer characters in The Friendly Young Ladies and other books). In this series she reveals an uncanny ability to bring lovely human details, and narrative coherence, to other extraordinary lives.

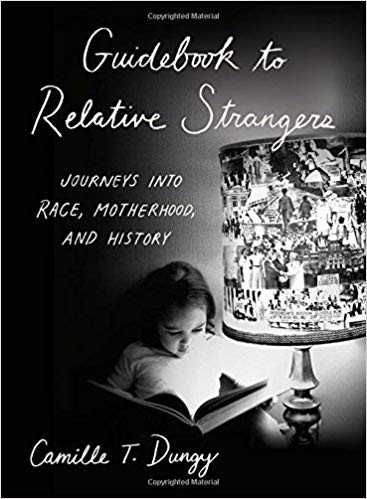

Guidebook to Relative Strangers by Camille T. Dungy

There have been so many wonderful books about motherhood recently that it is, comically, starting to take on the veneer of a “trend,” to the extent that it has even incited a mild backlash, or maybe fatigue, in literary culture. But this is a lovely work of memoir that I haven’t seen included in many of the roundups that accompany the “trend.” In this book Dungy, an esteemed poet, writes about her early years of motherhood as a working, traveling professor, describing trips around the country and world with her daughter Callie in tow. Dungy is excellent at combining the nitty-gritty mundane challenges of being with a child — my favorite is the description of trying to pee in an airplane lavatory while wearing a baby in a BabyBjorn — with notes on historical currents in America and the world, and how they play out in individual, everyday encounters Dungy experiences as a black woman. Dungy writes about slavery, race, racism, migration, the environment, and her multiple sclerosis diagnosis, because it turns out that motherhood is intertwined with all of these. There’s so much in this book, weight and levity. And her poet’s sensibility appears here and there in shimmering lines, like when her baby throws her weight against the Bjorn to crane her neck and head backward (a very specific display of shocking baby-spine strength most parents have felt): “Callie was looking at the tallest buildings she had ever seen, and she needed her whole self for this looking.”

The Debut by Anita Brookner

Here I’m going to take a moment and say that this assignment is hard because there are many, many women writers who have meant so much to me over the years, and I’m trying to stick with books that maybe don’t have the enormous audience they deserve, and even that’s such a difficult thing to measure. I had to use some blunt instruments (Iris Murdoch has a movie named after her! A Hollywood movie! So she’s not on the list, but I love her more than anything). Anita Brookner died in 2016 and was both a “Commander of the British Empire” and the subject of many great appreciations (like this one, or this one), but a certain…quietness, a certain overlooked-ness, is sort of tied up into her lore. The Debut was her first novel, and for an taste of the sort of reception she sometimes faced, just read this review of it — a perfect of example of the kind of review that is trying to be damning and patronizing while actually making the book sound incredible (I mean, “Grandmother Weiss, a somber refugee whose massive Berlin furniture and utter domestic competence dominate the scene.” Sign me up!) The Debut is about a Balzac scholar named Ruth, approaching middle age, who decides to make some changes in her life, after, among other things, lovingly cooking a chicken for a man who arrives too late to eat it. I’m not exactly sure how to describe the way that Brookner wrote her novels, which are about people, and relationships: she injected so much wry humor without making them comic, so much pathos without making them tragic. Her books just are, and The Debut just is, and you should read it.

Chronicle of a Last Summer by Yasmine El Rashidi

This recent novel is a beautiful example of how to make the political personal without becoming heavily didactic. It’s told from the perspective of a girl, then woman, from a relatively elite Cairene family during three epochs of Egyptian political life — in 1984, 1998, and 2014. There’s a beautiful economy to her lines: “The cleaning lady found Uncle in bed one morning a few months before the revolution.” There is a whole world contained there! And it’s an emblematic line, because the novel is sparse rather than crowded, the prose spare rather than florid. Nonetheless, confident in this economy, the book shows that politics are not an abstraction but a force that reshapes communities — the members of which are lost and found and lost at points throughout the book — and animates all levels of human relationships. I love the deft hand with which she shows how politics also change the material culture and physical fabric of a place — the food in the home and how it’s obtained, the topography of a neighborhood, the ways that people are employed. The city is its own, wonderful character in the book. It’s a melancholy model for how fiction can explicitly map the political movements that define our lifetimes. We need books like that, especially ones from women.

Off Course by Michelle Huneven

I’m not even the first person in this series to mention Michelle Huneven, but her novel Off Course became an instant touchstone when I read it a few years ago. For one, I had never read a book that took place so firmly in the “other” California — a place that was not L.A. or San Francisco (i.e., most of the state). The novel’s heroine, Cressida, starts out in Pasadena, but makes her way to her family’s cabin in the Sierra Nevada to finish her dissertation. The dissertation ends up taking a backseat to her dalliances with local men in the mainly seasonal community; one of these dalliances turns into something that, in a weird way, reorients the protagonist’s life. The novel is just a perfect evocation of the sort of what-the-fuck-am-I-doing moments that make up some of our lives (congratulations to the people who can’t relate!). And it does so without making the book about redemption or confession and absolution; it’s much more clear-eyed. It’s a beautiful example of writing about California and a what-the-fuck moment in a woman’s life, in a way that is both gentle and serious and incredibly aesthetically pleasing.

Read More Women is presented in collaboration with MCD Books.