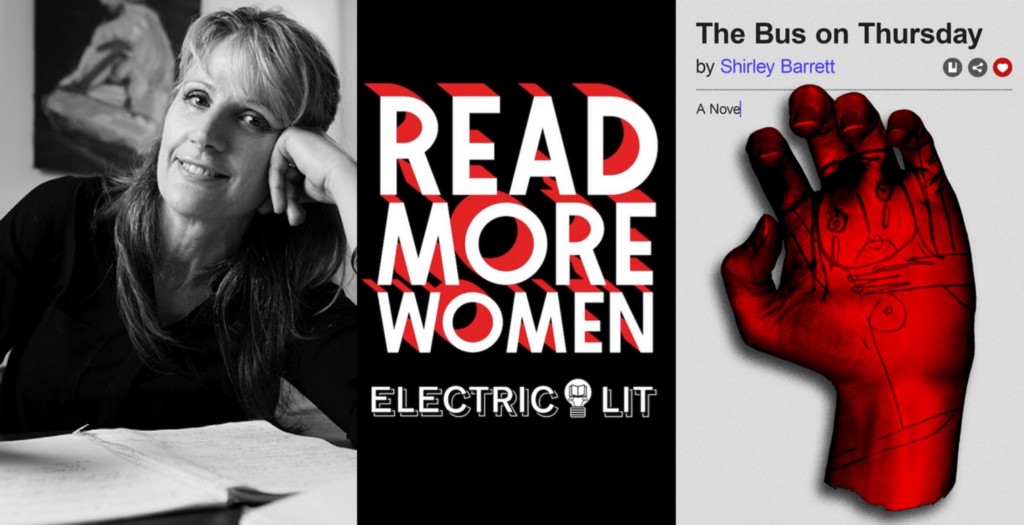

Read More Women

Shirley Barrett Recommends Five Horrifying Books That Aren’t By Men

The author of “The Bus on Thursday” recommends her favorite eerie fiction in this Halloween edition of Read More Women

Shirley Barrett’s The Bus on Thursday starts with breast cancer and only gets more horrifying from there. After cancer and a breakup, her main character Eleanor tries to drop out of her stressful life, running away to a small town in Australia to work as a schoolteacher—but she soon discovers that, like all the best small towns in eerie fiction, Talbingo is not what it seems. It’s part of a grand tradition of weird, dark, kinda creepy fiction—not ghouls-and-gore horror stories, but books that make the hair rise on your neck just the same. A lot of these books are written by women, and for Halloween, Barrett is here to introduce you to the best of them.

Read More Women is Electric Literature’s series, presented in collaboration with MCD Books, in which we feature prominent authors, of any gender, recommending their favorite books by women and non-binary writers. Twice a month, you’ll hear about the five non-male authors who most delight, inspire, and influence your favorite writers.

The Graveyard Apartment by Mariko Koike

Perhaps I have endured too many grim rental experiences in my life, for I regularly have nightmares where I find myself living in a dank and dingy hovel, my circumstances having somehow abruptly changed for the worse. The Graveyard Apartment plays upon our anxieties about accommodation, and in particular, the necessity of providing safe shelter for our small dependents, pets included. After years of renting a dark and poky flat, Teppei Kano and his wife Misao are suddenly able to buy their dream apartment: roomy, light and airy, and surprisingly affordable. Why so cheap? The building is surrounded on three sides by a graveyard, that’s why! “When they got up that first morning, the little white finch was dead.” That’s the first sentence and one pet is dead already! Things get worse rapidly, the unreliable elevator and creepy basement featuring largely; other tenants move out, and soon the Kano family find they are the only ones remaining in the building. Although she doesn’t hold back from conjuring up some lurid, visceral horrors, Koike keeps one foot firmly in reality, the horrible plausibility of our family’s situation (But we just bought this place! We can’t afford to move out!) making it all the more anxiety-inducing. So beautifully drawn is our little family (particularly small daughter Tamao) that one finds oneself caring desperately about their plight. Could you live so close to a graveyard, its crematorium constantly belching out plumes of black smoke? The novel finishes with a real estate ad for the now-vacant building, and yes, it does sound quite tempting.

“The Yellow Wallpaper” by Charlotte Perkins Gilman

I thought that I had written a very odd book, but this story, written in 1892, is one of the strangest, strangest stories I’ve ever read. “It is very seldom that mere ordinary people like John and myself secure ancestral halls for the summer,” the story begins. “..there is something queer about it. Else why should it be let so cheaply?” Exactly!, this reader wants to scream, especially having just finished The Graveyard Apartment. Get out of there if you know what’s good for you! Our narrator is suffering from an unspecified nervous condition, and her physician husband believes she must rest, installing her in the upstairs nursery where she is immediately struck by the wallpaper: “repellent, almost revolting: a smouldering unclean yellow.” As she spends more and more time confined to her bed, she becomes increasingly obsessed with this wallpaper, describing it in ever-changing detail, spending hours of her days and nights following its weird patterns, only mentioning in passing that she has a baby. “Such a dear baby! And yet I CANNOT be with him, it makes me so nervous.” Soon she begins to detect something beneath the wallpaper, a creeping woman trying to get out. I love this breathless, increasingly unhinged narrator: I love her hysterical use of CAPS, I love this story. It makes you want to read it again and again to try to FIGURE IT OUT, especially the ending.

“The Lottery” by Shirley Jackson

I’ll never forget the physical sensation of shock I received when I first read this extraordinary short story in an anthology that gave no hint as to what kind of story it was. Told so simply, without any obvious striving for effect, Jackson lulls you into thinking you are reading about a group of jovial, good-natured villagers gathering together for some kind of annual fete. Children play, couples joke with one another, Mrs. Hutchinson is late because she has been doing the dishes and almost forgot that it was Lottery Day. Then as the villagers’ names are drawn from the box, the tension begins to build. Someone mutters that in the neighboring village, there’s talk of giving up the lottery. Old Man Warner will have none of it. “‘Pack of crazy fools,’ he said. ‘…Used to be a saying about “Lottery in June, corn be heavy soon.” First thing you know, we’ll be eating stewed chickweed and acorns.’” Re-reading it a second time recently, I couldn’t remember exactly what the shock was, and thus it packed its wallop all over again. The worst moment? Someone giving little Davy Hutchinson a few pebbles. I’m getting chills down my spine just writing about it. Truly a masterpiece.

Mrs. Caliban by Rachel Ingalls

More a fantastic tale than a scary one, this slow-burning novella nonetheless steadily ratchets up the mounting dread, the sense that this can not possibly end well. How could it? Dorothy has fallen in love with a six-foot-seven-inch sea creature known as Larry, recently escaped from the Jefferson Institute for Oceanographic Research. He suddenly materializes in her kitchen one evening; they find themselves staring at each other. “Her mouth was slightly open — she could feel that — and waves of horripilation fled across her skin. A flash of heat or ice sped up her backbone and neck and over her scalp so that her hair really did seem to lift up.” She offers him celery, he thanks her, a love story ensues. The police are after him; she hides him in the guest bedroom and feeds him bowls of salad and pasta, a secret she keeps from her uncaring husband who only notices enough to complain that she’s buying an awful lot of avocados lately. It’s all preposterous, like a 1950s sci-fi crossed with a Douglas Sirk melodrama! But the story is told so solemnly (and yet with moments of sly comedy), and poor lonely Dorothy so beautifully wrought that the reader accepts it all, turning pages with sinking heart and dry mouth as events build towards the inevitable tragedy. But hang on a minute! you think suddenly, about three days later (I am a little slower than most, admittedly.) What about those strange radio messages that Dorothy kept hearing? Was Larry even real, or has Rachel Ingalls taken me on a wild ride?

Fever Dream by Samanta Schweblin

“I call it the ‘rescue distance’: that’s what I’ve named the variable distance separating me from my daughter, and I spend half the day calculating it, though I always risk more than I should.’ The daughter, Nina, is only small: her mother frets continually about this rescue distance as the horrors mount in this truly disturbing, nightmarish book that, yes, feels exactly like a fever dream if our fever dreams were half as imaginative. Told as a two-hander, a dialogue between the unnamed mother now mysteriously marooned in the emergency clinic and a small boy named David, who is urgently interrogating her. He wants to know the exact moment the worms, “something very much like worms,” have come into being. When she deviates from her account of what has happened, he admonishes her sternly: “None of this is important. We’re wasting time.” It’s apparent that she will die soon, but what has become of Nina? Where is she? The story is set in the muddy landscape of rural Argentina, where they have apparently travelled on some ill-advised holiday, only to find that the stream is polluted, the horses are dead and so are the birds. And something terrible is happening to the children. I read the whole book with a ghastly maternal anxiety gripping my heart — stay closer to Nina, I wanted to cry, don’t let that rescue distance slacken! Suspenseful and dread-filled, this book races along to its remorseless conclusion. Of all the books I’ve volunteered in this piece, this one really got under my (goose-bumped) skin. Extraordinary.