Read More Women

Warren Ellis Picks 5 Books By Women You Should Read

The comics giant contributes to our Read More Women series

Listen, just because we’re a literary website doesn’t mean we’re above loving comics giant Warren Ellis—author of Transmetropolitan, Planetary, The Authority, Nextwave, and the criminally underrated Desolation Jones among many, many others. So when we found out that Ellis also published his third non-graphic novel Normal with FSG, parent publisher of our Read More Women partner MCD Books, we just had to see whether he’d contribute to the series. Even in the macho world of comics, Ellis has always written interesting, funny, cliché-defying female characters—so which non-male authors does he recommend? These picks are adapted from Ellis’s newsletter Orbital Operations, which includes book reviews among other news. (On the subject of cribbing his RMW picks from his newsletter, Ellis writes: “Hi. I’m a man. We cheat. All the time.”)

Read More Women is Electric Literature’s series, presented in collaboration with MCD Books, in which we feature prominent authors, of any gender, recommending their favorite books by women and non-binary writers. Twice a month, you’ll hear about the five non-male authors who most delight, inspire, and influence your favorite writers.

The Book of Joan, Lidia Yuknavitch

The Book of Joan is a science fiction story about women. Women who love, women who hate, women who kill, women who destroy. It’s a story about what happens after the end of the world, where (another) other-humanly elite has gone to orbit to live out sexless, loveless lives of bizarre art and ritual.

Christine Pizan, a denizen of the orbiting station that may be all that’s left of the human race, is an artist of skin. Through a braille-like process of branding and skin grafts, she wears stories on her skin. She is the Book of Joan—Joan being Joan of Dirt, the superhuman child soldier who fought the good fight down below and was burned at the stake for it. The term used for Joan’s superhuman condition is engenderine—from engender, whose more archaic definition is “to cause to be born.”

Any book that starts with a quote from Doris Lessing’s mighty Shikasta has me on its side.

The medieval writer Christine de Pizan’s last work was an eulogy of Joan of Arc.

The station is run by a mad misogynist called Jean de Men. De Pizan’s intellectual status in her time was partly made by her dissection of the misogynist writer Jean de Meun. Not being a student of the period, these are things I learned after reading the book. Joan of Dirt is an obvious avatar of Joan of Arc, but I didn’t know the rest. It didn’t make the book any less fascinating to me.

It’s not a happy book, I warn you. There are moments of joy that blaze through it, but, contra to the first quote above, it’s a book about war and women, and birth and the earth. It’s a huge fable about the end of the world, told with pieces of history. It is ambitious, frequently beautiful, and weirdly haunting.

The Only Harmless Great Thing, Brooke Bolander

A short book full of big explosions of language. It is an alternate-history of the Radium Girls crime, mashed up with a few other historical occurrences that I don’t want to mention because spoilers. I’d love it if you could come to this book clean.

Which makes it more difficult to talk about.

There are three timelines. In the present day, Kat is trying to solve the problem of marking radioactive waste dumps so that future generations know to avoid them. Which is a real-world thing you should look into sometime, it’s fascinating. A hundred years ago, Regan, a Radium Girl, is dying of cancer and finding her agency. In the deep past, there are myths and legends of elephant culture, passed down through the elephant generations.

Elephant cognition has also been a subject of recent conjecture. This is proper speculative fiction. Bolander adds an elephant-human sign language to great effect. The book is beautifully structured, very inventive (the Disney connection is genius) and generally just a goddamn joy to have discovered in my Amazon Kindle trawling.

Bolander’s conjuring with language, though, is the greatest delight of all the book’s many pleasures.

Kat turns her back on the memorial and the roaring Atlantic dark and shuffles towards the garish electric dawn of Coney Island, some skeleton’s memory of what progress looked like.

Some skeleton’s memory of what progress looked like. I would have paid real money to write a sentence like that.

Origamy, Rachel Armstrong

There’s a field of rogue mutant hair transplants, and the hair field is grazed upon by a trip of transgenic goats, and there’s like five pages on the digestive processes of these goats, including shoals of microsquid that live in one of the four stomachs. And it’s brilliant.

If you’re not up for that: the book is about people who use chopsticks to tie knots in spacetime for travel purposes. And art.

Rachel is a synthetic biologist—I met her at a think-tank in Eindhoven a few years ago—and Origamy is what happens when you let a synthetic biologist write a full work of speculative fiction. Possibly this practice will be banned after Origamy is released.

It’s an incredibly dense piece of bizarre fantastika balanced artfully on a very simple structure, a journey of discovery, secrets and ancient threats. Parts feel like they’ve come from fable, or folk tales about strange circus people. In reading it, I’ve gotten through about ten pages at a time before having to stop and stare into space and process everything that’s just been dumped into my head. It’s like she freebased twelve novels into one intense concentrated rock.

Origamy is a magnificent, glittering explosion of a book: a meditation on creation, the poetry of science and the insane beauty of everything. You’re going to need this. Frankly, there are only people who have read Origamy and people who have not, and neither of them are able to understand the other.

At the Existentialist Café, Sarah Bakewell

This book is a wonder. It’s the story of existentialism. By which I mean: this is the story of crazy people and wonderful people and fucked-up people and dancing and drinking and thinking people. It starts with someone in a cafe in Paris explaining a new form of philosophy using a cocktail. Meanwhile, in Germany, a man is yelling for coffee so that he can make that philosophy out of it. This is phenomenology, which gave rise to existentialism, and Bakewell tells it all in terms of cafe conversation and jazz clubs and old houses and shacks in the woods, in occupied cities and military stations and mad dashes across borders, alternating between biography and the sort of clear, warm explanations of philosophical ideas that even uneducated laypeople like me can grasp. Husserl, Heidegger, Camus and the like are all here, and, of course, Sartre, but also, thank god, Simone de Beauvoir gets significant space, and pleasingly, so does the dancing master of humanism, Merleau-Ponty. I did not want this book to end. It’s marvelous. A great story, and, in some ways, a valedictory one, of the days before philosophy was completely subsumed by academe and became a thing of technical language and minor considerations. (Side effect: if you’ve ever visited Paris, it will really make you miss it.)

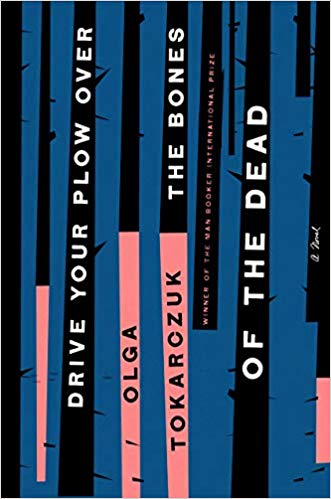

Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead, Olga Tokarczuk, translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones

It’s a crime story. It’s also a study in isolation and mental illness. And a masterclass in literary eccentricity. For example:

“He was a man of very few words, and as it was impossible to talk, one had to keep silent. It’s hard work talking to some people, most often males. I have a Theory about it. With age, many men come down with testosterone autism, the symptoms of which are a gradual decline in social intelligence and capacity for interpersonal communication, as well as a reduced ability to formulate thoughts. The Person beset by this Ailment becomes taciturn and appears to be lost in contemplation. He develops an interest in various Tools and machinery, and he’s drawn to the Second World War and the biographies of famous people, mainly politicians and villains. His capacity to read novels almost entirely vanishes; testosterone autism disturbs the character’s psychological understanding.”

The protagonist’s narration is just fascinating, and a joy to read. She lives on a plateau, somewhere in southern Poland near the Czech border, shares with a few other hermit types and a lot of animals. One night, one of those hermit types is found to have died. And the protagonist finds evidence suggesting it may not have been a simple death.

I don’t want to say a lot more about it, save that the mystery—and the deaths that follow—tangle up the supernatural with the ecological and the social and even the literary, without ever really breaking the spell of one estranged and lonely and aging woman who is a head smarter than anyone else she knows dealing with loss and damage and distance and an unexplained death that nobody else seems to want to solve.

It is fierce and golden and kind of heartbreaking and another phenomenal choice from one of my favorite publishers, Fitzcarraldo. There’s nothing else quite like it.