Read More Women

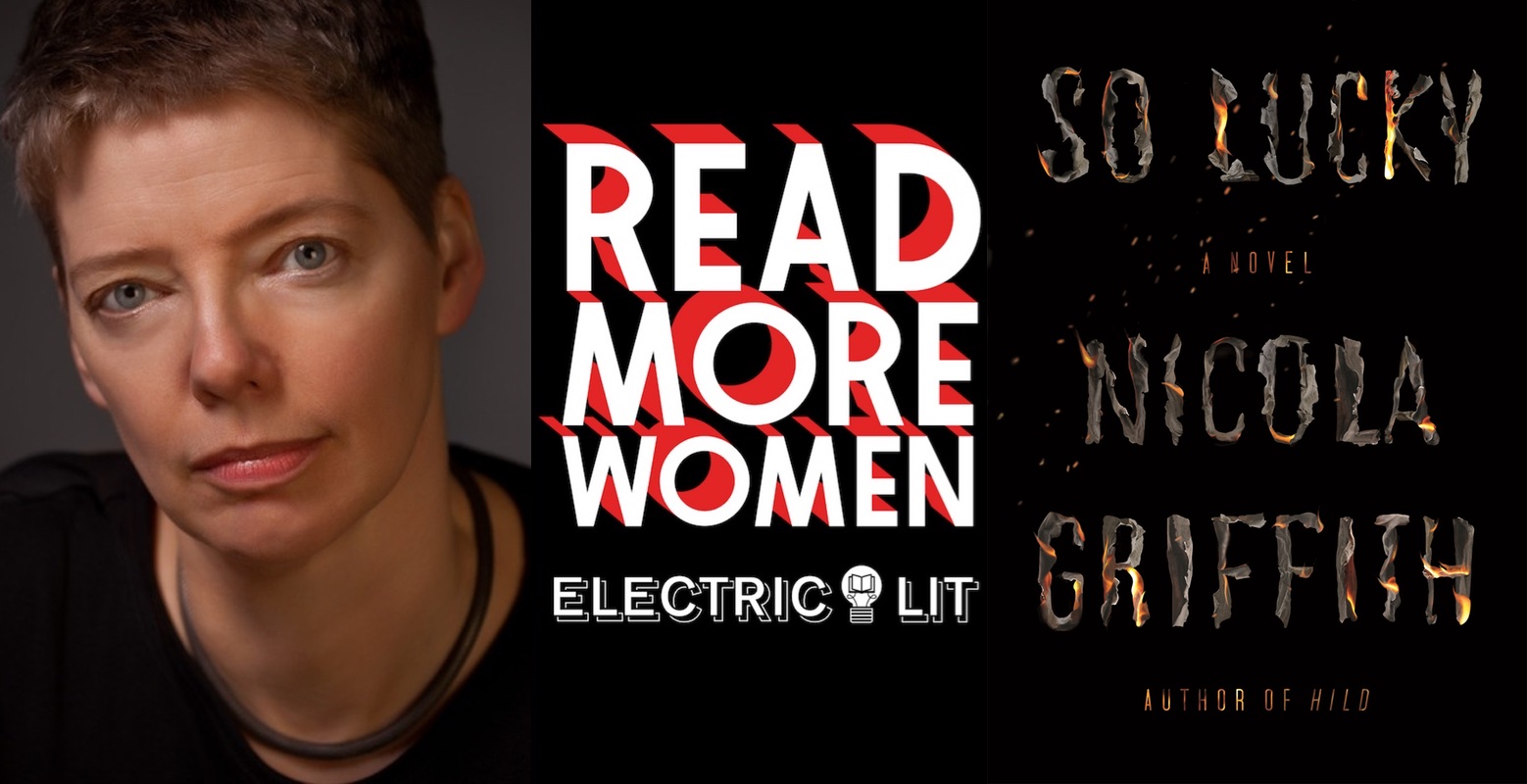

5 Great Books by Women, Recommended by Nicola Griffith

The author of "So Lucky" picks favorites for our Read More Women series

Nicola Griffith, most recently the author of So Lucky, may have the distinction of being our first Read More Women participant who’s also been recommended by another participant: Robin Sloan described Hild, her novel about a gifted young woman in seventh-century England, as “deep, cat-purr pleasure.” So Lucky, a semi-autobiographical novel about chronic illness, brings the action much closer to home, but with the same depth and generosity.

Read More Women is Electric Literature’s series, presented in collaboration with MCD Books, in which we feature prominent authors, of any gender, recommending their favorite books by women and non-binary writers. Twice a month, you’ll hear about the five non-male authors who most delight, inspire, and influence your favorite writers.

Mary Stewart, The Crystal Cave

As a child I read and still occasionally reread Mary Stewart’s The Crystal Cave, a potent and atmospheric entry in the Matter of Britain—Uther, Merlin, Arthur and the fight of Light and civilization vs. Dark and barbarism. It is heady stuff: menhirs looming from the mist, the scent of woad and wet wool, and moonlight gleaming on chased hilts and chainmail as noble warriors gather to stoop down on invaders like wolves from the fold. So far, so Dark Ages. But unusually for the genre, women are not rape toys—in fact they are largely absent, leaving 10-year-old me to imagine myself in the hero’s saddle. And the hero is not a warrior but Merlin.

Stewart chose well. The prevailing historical wisdom of the time was that in an era of petty kings and warlords, women of any class were victims without sufficient agency to do anything interesting. So Stewart writes about a man, one who is twice royal—but a bastard; straight but not a man of the sword. Rather Merlin is an instrument of divine power, his sexuality subordinated to his priestly role as mouthpiece of the Light. He is mocked by his princely contemporaries for gender noncompliance but, even as they laugh, the reader—that is, 10-year-old me—knows that he holds a far greater power than any blade. It’s enormously satisfying when he gets to flash that awful power and make those manly men go white around the eyes and tremble. Basically he’s a witch in boy drag.

What I really loved about this book, though, is how Stewart immerses us in nature. We feel it, smell it, and hear it; it seeps into our bones and infuses us with a sense of immanence and wild magic. It was this book, and Sword at Sunset by Rosemary Sutcliff, and Fire From Heaven by Mary Renault, that fired my longing to experience the landscape where I grew up without contrails and car exhaust, to feel how it might be for a woman, in a time when might was right, to be powerful enough in, of, and for herself to make a difference, to be a hero.

Mary Barnard, Sappho: A New Translation

In my early twenties I was reading a lot of novels but writing only lyrics: songs for the band I fronted. When the band faded away, as all bands do, I found I didn’t want to stop writing. So I wrote poetry; I wrote nonfiction. Something began to gather in the back of my brain but I couldn’t access it. Then I found Mary Barnard’s translation of Sappho.

Without warning

As a whirlwind

swoops on an oak

Love shakes my heart

Her bold, vertiginous leaps shocked me awake and open the dam in my head. I wrote 30,000 words of a novel in five days. This, I realized. This is what I will do with my life.

But, like Stewart’s, it was Sappho’s language of the the natural world, specifically using that language to talk about the body, that lit something in me. Her lyrics are fresh and astonishing. As Barnard herself says in her footnote, some of her words feel invented in that moment for that line alone. She was writing more than 2,500 years ago, yet her works speaks directly to us even today. So many of what we consider literary clichés were her original imagery: silver moon, rosy-fingered and rosy-armed dawns and moonrise, turning pale, being tongue-tied. She shaped our understanding of what it is to be human.

Suzy McKee Charnas, The Slave and the Free

Poetry by and about women has never been too hard to find, but for a while I could find no historical fiction and very little contemporary fiction about women that was not romance. So I started to read about the future—but that, too, was about men, with the occasional space bimbo or scientist’s daughter thrown in to be explained to or rescued. I despaired until I discovered feminist science fiction. Here I’m going to cheat and talk about The Slave and the Free, an omnibus volume of the two first and best novels in Suzy McKee Charnas’s Holdfast Chronicles, Walk to the End of the World (1974) and Motherlines (1978).

Walk to the End of the World commits to an implacable sci-fi logic of post-apocalyptic gender war. The world is largely arid and inhospitable, with small isolated populations clinging on here and there. In one region men hate women, and fuck them not for pleasure but to make babies. Women are domesticated animals: bred as both beasts of burden, and food. We follow the story of one pregnant slave, Alldera, and her eventual escape. We have no idea what she’s escaping to, if anything, and if she’s walking into certain death in the desert, it seems like a reasonable choice because Walk to the End of the World makes The Handmaid’s Tale feel like a tidy little bedtime story. Like “Cold Equations,” a story that shocked a generation of science fiction readers with the relentlessness of physics, it does not flinch from its premise. It will give you nightmares, and those nightmares have teeth.

But Alldera does escape, to the world of Motherlines, a world of all women who breed their own domestic animal: not fellow humans, but horses. This is a much less terrifying book but it, too, looks right into the face of brutal choices and doesn’t blink. It was the first book I read with no men in it at all, and refutes essentialism effortlessly. For a new writer it is a marvelous introduction to, and almost perfect exemplar of, show-don’t-tell: a master class disguised as feminist legend that never was.

If you want to understand the shape of 21st-century science fiction, read Charnas and Vonda McIntyre’s Dreamsnake (1978). They are the others of us all.

Octavia Butler, Kindred

I loved reading Charnas’s and McIntyre’s futures in which women had space to roam, but I was also getting hungry for fiction by a woman about a woman set in a recognizable present. I remember picking up a copy of Octavia Butler’s Kindred, marveling at the cover illustration—a black woman who was neither half-dressed nor being threatened by a man. I had to read it—and instantly finding myself in familiar science fiction territory: time travel.

In 1976 Los Angeles, Dana, a young black woman married to a white man, is somehow called to the antebellum South to save a young white boy from drowning. She does and, bang, she’s back in L.A. But the boy, Rufus, ends up summoning her to save him every time he’s in danger. And Dana has to keep saving him to ensure her own existence, because he is the father of one of her ancestors. Each visit to the past—in which the people in the past age while Dana does not— is worse than the last, until she finally frees herself by killing the adult Rufus, already a father. What makes all this work as realism is that Dana does not escape unscathed, and her loss is tangible, not just internal and metaphorical: she loses teeth, and her left arm.

This is a book for all those women (and queer folk, and people of color) who look at their elders and sneer: I wouldn’t have knuckled under like you did! Why didn’t you fight back?? Butler shows that people in every time often do the best they can in the circumstances—probably better than you or I could—and it’s a miracle they survive, never mind conquer. History is never the inevitable, magisterial story we’ve been told; history is contingent upon circumstance, and the circumstance here is structural oppression.

This had a big impact on my work, as did two other things. One, the way Dana learns the reality of master and slave via personal, visceral experience: somatic knowledge that helps her unlearn the extra-somatic modes of dry text and TV representation. Two, that the notion of a protagonist as lone hero is bullshit; survival is all about being a member of a group, embedded in a network of others—and one’s actions have consequences beyond oneself.

In terms of craft I was fascinated by Butler’s nicely calibrated Othering. Dana suffers; her life as a slave is brutal—but not too brutal. Clearly Butler understood the nature of narrative empathy: put the reader inside your character and the character inside your reader, make them feel what they feel and learn what they learn, but don’t make it too hard, because if you do, the reader will put the book down and walk away, or at least barrier themselves up emotionally. Butler knew you can’t change the world unless you change the reader, and you can’t change the reader unless she stays open to your fiction’s great power of empathy.

Joanna Russ, Extra (Ordinary) People

Joanna Russ’s “When It Changed” (1972) was the short story that perhaps had the most immediate impact on me (Ammonite could not exist without that story), but here I want to talk about “The Mystery of the Young Gentleman,” (1982) a novelette in her brilliant collection, ExtraOrdinary People. It’s my favorite piece by Russ: fast-moving, thrilling, and sly.

It’s set on a clipper ship sailing from England to the U.S. in the late 19th century, narrated by a—well, I’ll have to say “woman,” because if you follow the textual clues that’s what makes most sense, biologically speaking at least. Though s/he could, just possibly, be an alien. And of course the point of the story is to deconstruct the notion of gender’s pernicious binary, throw out the Either/Or and replace it with Neither/Nor and a sprinkle of Yes/And. The narrator does not identify as gendered at all but, Wittig-like, insists that among their people there are no men and no women: if all refuse gender, there’s no need to perform it.

So, It’s about a woman with a young charge—who is definitely a girl, or more precisely a young woman, but in any case most certainly not a lady, oh no—who are traveling as father and daughter. Though, oh dear me, their relationship is not filial. At all.

So, It’s about a woman and girl on a transatlantic crossing who use gender performance to stay safe. Not safe from bad men. Safe from the dull-eyed herd, each plodding behind the placid beastie ahead. Our protagonists, you see, are telepaths. And Russ has a tremendously fine time fucking with everyone’s gendered heads as she ratchets up the stakes.

So, It’s sharp, witty, genderqueer science fiction. But we are talking about Russ, so that’s not all it is. It’s pulp adventure fiction, with sex and gunplay and gambling, money and reversals and danger. Also a parody of Victorian porn. And, literally, a comedy of manners. Exhilarating stuff.

Another great piece in this collection is “Souls.” Abbess Radegunde slices open the clichés of Dark Age Britain, salts them, and eats them.

Finally, if you want to know why, despite campaigns like #ReadMoreWomen, women still aren’t read, respected, or rewarded when we write about women, read Russ’s magnificent How to Suppress Women’s Writing. And then take the Russ Pledge: whenever you talk about books, talk about books by women about women.