Recommended Reading

Recommended Reading’s 32 Most Read Stories of the Decade

We dove into the archives and called in the accountants

INTRODUCTION BY THE EDITORS OF RECOMMENDED READING

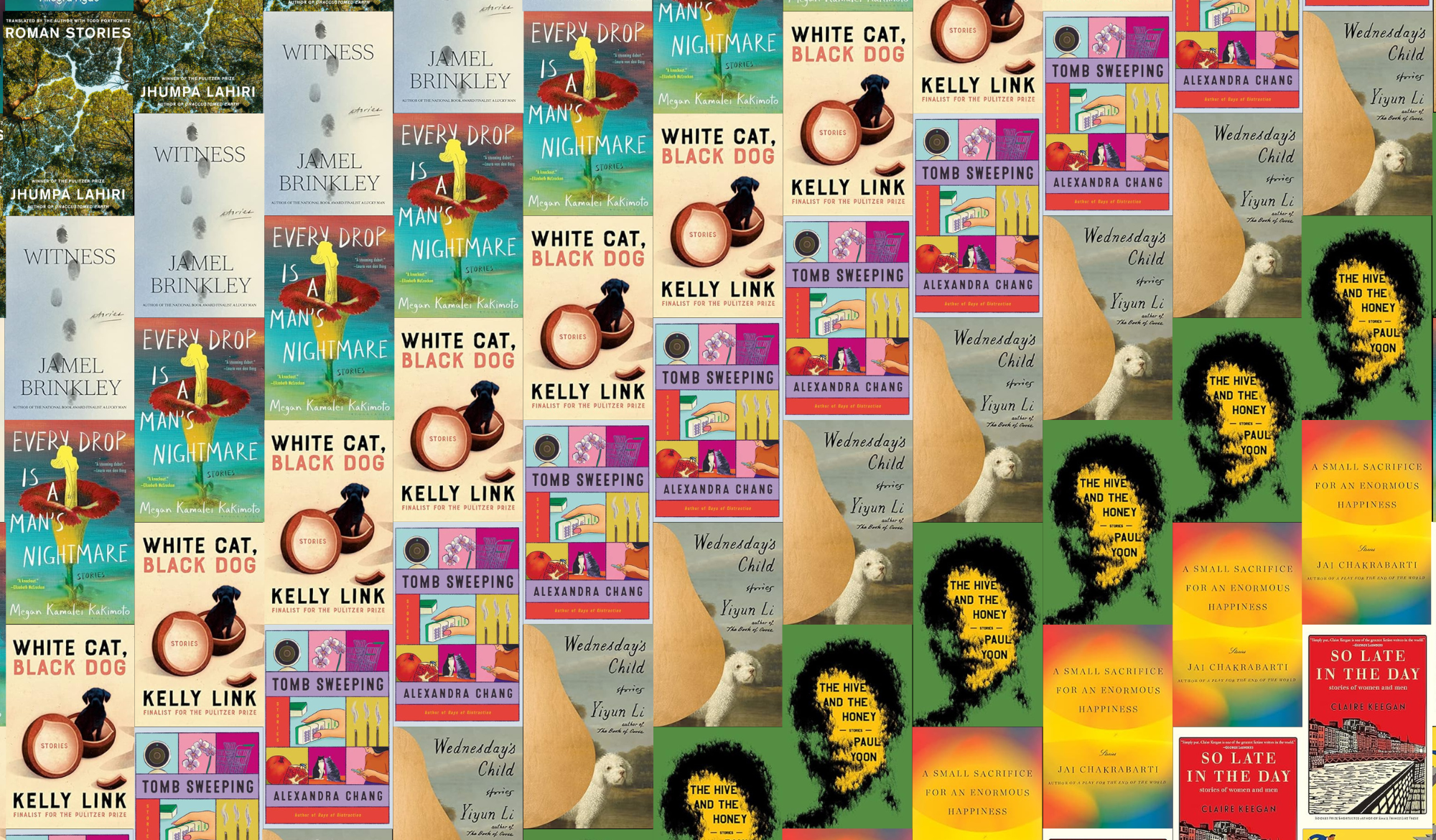

Our list of the 32 most popular stories in Recommended Reading this decade have some heavy sperm to worm vibes. There’s a way to view every story on this list as either being about sex, or about death. Maybe sex and death are less like themes and more like the stuff of life.

We have stories about about preparing to die, about wanting to die but instead surviving, about avoidable death brought about by incompetence, one about vampires, another about zombies, another about a ghost and yet another about a childlike scarecrow or a scarecrow-like child. Animals don’t fare too well either: birds are eaten, families are stalked by bunnies, dogs are euthanized, and Barthelme’s classroom pets get it every time.

On the other side, people make love or they fuck, they negotiate relationships on front porches and in family homes, at the Thanksgiving table and in the visiting rooms of prisons. They sleep with their friends and make friends of the people they’ve slept with, they call each other out—online, in letters, and face to face.

If there’s any lesson to be learned from this impressive array, it’s the limitless capacity of short stories and literature in general to boldly imagine and re-imagine what it means to be a person, what it means to be alive.

Since May 2012, Recommended Reading has published 398 issues on at least 5 different websites (which means there may be some formatting issues—we’re working on it). One of the stories on this list, ”The Bastard” by Partick DeWitt, was first printed in our quarterly journal in 2010 and was republished online in 2016. We have better analytics for issues post 2014, so to account for that inconsistency we’ve selected the four most read stories from each year. And because this is a short story list, novel excerpts have been excluded.

Happy reading, and happy New Year.

– Halimah Marcus, Brandon Taylor, and Erin Bartnett

Recommended Reading’s editorial team

Recommended Reading’s 32 Most Read Stories of the Decade

Electric Literature

Share article

2012

“Birds in the Mouth” by Samanta Schweblin

“Birds in the Mouth” was the title story of Schweblins second Spanish-language collection, Pájaros en la boca, and was included in her 2019 English language collection, Mouthful of Birds. The story was first published in English in the PEN American journal, translated by Joel Streicker with the support of 2011 grant from the PEN translation fund. It appeared in Recommended Reading in 2012 with an introduction from the editor of PEN America, M Mark.

In her introduction, Mark writes, “’Birds in the Mouth’ is narrated by a seemingly reliable divorced father who’s worried sick about his thirteen-year-old daughter and her mysterious appetites. The daughter, it turns out, eats birds. Live birds. And the trustworthy narrator occasionally mentions details about himself that seem a bit off-key. When I first encountered this story, I found myself, almost without realizing it, pushed to look at the family from unexpected angles and finally forced to ask questions about the characters, their world, and my own. How do we ask for attention from those we need? How do we give enough of ourselves to those who need us? What sorts of nourishment, and how much, must we have to survive? What is normal? What is forbidden?”

“Cattle Haul” by Jesmyn Ward

“Cattle Haul” by Jesmyn Ward was originally published in A Public Space, Brooklyn-based literary magazine publishing since 2006, and was introduced in Recommended Reading by the APS’s editor Brigid Hughes in 2012. The story is about a young trucker named Reese who hauls goods, sometimes livestock, back and forth across the country. The work is exhausting, the pace relentless, but he needs the money. The profession is also in his blood. His Dad’s a trucker, too, and some of the things he’s learned from his father about how to stay awake on the road are more damaging than they are helpful. In her acceptance speech when she won the National Book Award for Salvage the Bones the year before this story appeared in RR, Ward said, “I wanted to write about the experiences of the poor, and the black, and the rural people of the South so that the culture that marginalized us for so long would see that our stories were as universal, our lives as fraught, and lovely, and important.” She went on to write Sing, Unburied, Sing, which was recently named one of the 10 Best Fiction Books of the Decade by Time Magazine and the memoir The Men We Reaped, which was named one of the Best Books of the Century by New York Magazine.

“My Last Story” by Janet Frame

Janet Frame was born in New Zealand in 1924. Over the course of her career, she has received numerous awards and published thirteen novels, two of them posthumously. Due to suicidal ideation, Frame spent much of her twenties in and out of psychiatric facilities, where she was eventually diagnosed with schizophrenia and received electroshock therapy. In 1951, she was scheduled for a lobotomy, which was canceled when her short story collection, The Lagoon and Other Stories (which included “My Last Story” and appears to be out of print), was awarded the Hubert Church Memorial Award.

The life-saving power of stories and the despair often associated with writing them is the context for “My Last Story,” which Etgar Keret selected for Recommended Reading in 2012. In his introduction, Keret writes, “I have always been interested in stories that have to do with writing. Stories that remove the insoluble question of the nature of creativity from its permanent blind spot and place it front and center.

“The problem with texts of that kind is that, in many cases, they are clever, but almost never moving. As if that reflexive sort of writing moves writers to their mind and away from their heart. There are, of course, exceptions, and Janet Frame’s ‘My Last Story’ is one of them…Like all writers, Frame had no pragmatic reason for making up stories, but the fiction she created had a clear and pragmatic effect on her life: writing kept her complex, sensitive mind whole.”

“North Of” by Marie-Helene Bertino

Jim Shepard selected Marie-Helene Bertino’s debut collection, Safe as Houses, to win the Iowa Short Fiction Award. When recommending her story “North Of” to our readers, Shepard wrote:

“I haven’t been as won over by a story as completely as I was by Marie-Helene Bertino’s ‘North of’ in years. I loved it of course for its deadpan comedy, much of which centers around its celebrity co-star Bob Dylan’s self-absorbed obliviousness. His mostly unswerving focus on whatever keeps him happy and comfortable in the moment — whether it’s a well-cooked string bean or a search for Tootsie Rolls — is an inspired counterpoint to everyone else’s emotional maelstrom: the narrator’s brother, a roil of resentment and rage and contempt for himself and everyone else; her mother, whose expectations have now shrunk to the hope that they can pull off one Thanksgiving meal without a blowup; and the narrator herself, with her perpetual desire to please, who performed the double fuck-yous of becoming a success and staying away, and knows it.”

“North Of” was first published in the Mississippi Review in 2007 and then collected in the Pushcart Prize XXXIII anthology in 2009. Bertino’s novel, 2 a.m. at the Cat’s Pajamas was published in 2015, and her next novel, Parakeet, is forthcoming from FSG in June 2020. Her story, “Carry Me Home, Sisters of St. Joseph,” is also available in Recommended Reading.

2013

“The Knowers” by Helen Phillips

Helen Phillips was first published in Recommended Reading in 2013. Since then, she has published two novels, The Beautiful Bureaucrat, which we excerpted, and The Need, which was longlisted for the National Book Award and which one of Electric Lit’s best novels of the year. “The Knowers” was included in her collection Some Possible Solutions along with “The Doppelgängers,” which can also be read in Recommended Reading with an introduction by Lauren Groff.

In his introduction, former Recommended Reading co-editor Benjamin Samuel writes, “’The Knowers’ is a story set in a world where people may choose to learn the date — although not the circumstance — of their own demise. The information is not prophecy, it doesn’t come from an oracle or the supernatural, but a machine that appears as humdrum as an ATM.

“The narrator of ‘The Knowers’ is both empowered and burdened by the revelation of her doomsday: the monumental date is delivered on a scrap of paper easily destroyed but impossible to forget. Every moment is informed — clouded or enlivened — by that date, ‘I regretted knowing,’ she says. ‘I was grateful to know.’”

“The Graveless Doll of Eric Mutis” by Karen Russell

“The Graveless Doll of Eric Mutis” was first published in Conjunctions and later collected in Russell’s 2013 collection, Vampire’s in the Lemon Grove. The collection followed her critically acclaimed and wildly popular novel, Swamplandia!, which was a finalist for the 2011 Pulitzer Prize. Her latest collection, Orange World, was one of Electric Literature’s 15 Best Short Story Collections of 2019.

In his introduction to the story, Conjunctions editor Bardford Morrow writes, “‘The Graveless Doll of Eric Mutis’ is narrated by a young adolescent named Larry Rubio who, with his three Anthem City, New Jersey, buddies Mondo, Gus, and Juan Carlos, discovers a scarecrow lashed to an oak tree in the city park. As always in Karen’s work, the narration is heartbreakingly empathetic and intimate, but the boys are nonetheless clearly drawn as violent bullies, and the scarecrow is an unsettlingly lifelike — or deathlike — doppelgänger of one of their victims, the titular Eric Mutis, an epileptic outcast who may have suffered abuses at the hands of adults that far outstripped the traumas doled out by our protagonists. It’s revealed that Eric vanished from Larry’s school and neighborhood prior to the appearance of the scarecrow, a disappearance silent and unremarked at the time, which later becomes mysterious and troubling.

“This bewitching story addresses many of Karen’s biggest themes: identity and the complexities of growing up, innocence and aloneness, people in search of their souls. Like so much of her work, it locates a perfect balance between the comical and calamitous, the familiar and the fantastic.”

“Bettering Myself” by Ottessa Moshfegh

“Bettering Myself” by Ottessa Moshfegh was published in The Paris Review in 2013, and introduced in Recommended Reading by its former editor, Lorin Stein after Moshfegh won the Plimpton Prize for Fiction for her two stories, “Disgust” and “Bettering Myself.”

“‘Bettering Myself’ did what it said it would,” Steu writes, “it convinced me that Moshfegh was even better than I already thought. The voice here is totally unlike that of “Disgust.” It’s a sharp-witted, wayward, unpredictable first-person voice, evidence that Moshfegh is a writer of significant control and range. The narrator of “Bettering Myself” is a problem drinker and Catholic school math teacher who says to her students, “Most people have had anal sex. Don’t look so surprised.” There’s a deadpan humor to many of Moshfegh’s utterances. A little Henny Youngman in there, trying to break out. But also something a whole lot sadder … What distinguishes her writing is that unnameable quality that makes a new writer’s voice, against all odds and the deadening surround of lyrical postures, sound unique.”

Moshfegh went on to publish her novella McGlue, which we excerpted in 2014, with Fence Books, followed by Eileen, which won the Hemingway Foundation/PEN Award, and My Year of Rest and Relaxation, which was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize.

“Yours” by Mary Robison

The editor, novelist, and critic Ben Greeman selected this story by Mary Robinson in 2013. Robinson is one of the patron saints of minimalist writing, a style Greeman praises in his introduction: “Robison is classed as a minimalist, which means not very much, both in the sense that it literally refers to writers who pare down their fictional materials and in the sense that it is a largely meaningless distinction. What is minimalist about the first sentence of this story? We see a woman ‘struggle away from’ (not back away from, not step away from, not turn or swivel) her ‘white Renault’ (it’s the only traditionally modified noun in the sentence, and thus both too important and not important at all), ‘limping with the weight of the last of the pumpkins.’ In the last movement of this sentence, there is almost too much to bear: we get the season, and a sense of her misplaced ambition, and a whiff of depletion and possibly depression,but also of things held tightly for value.

“By the second sentence, we have another character, and by the next paragraph we have a whole set of relations between them and their objects. The rest of the story follows Allison and her much older husband Clark through what remains of the day, moving around them as they perform mundane tasks, leaning in when something glints in the evening light: an insight, a self-doubt, a joke, an oblique gesture of love.”

2014

“The School” by Donald Barthelme

After J. Robert Lennon selected Steven Polanksky’s story, “Leg” for Recommended Reading, we invited Polansky himself back to recommended a story. Polansky chose one of the classics of the form, “The School” by Donald Barthelme. In his introduction, Polansky writes, “Barthelme’s short fiction is unapologetically difficult. In a 1987 essay, ‘Not-Knowing,’ Barthelme writes: ‘Art is not difficult because it wishes to be difficult, rather because it wishes to be art. However much the writer might long to be straightforward, these virtues are no longer available to him. He discovers that in being simple, honest, straightforward, nothing much happens.’”

When I knew him, Barthelme was in his early forties. He died in 1989, at the age of 58. ‘The School’ which appeared first in the 1976 collection, Amateurs, is one of Barthelme’s more accessible stories. To describe it is to sound ridiculous: a very funny story about death and the negation of meaning, and the only story ever written, by anyone, in which a resurrected gerbil is the bringer of hope.”

“Safety Tips for Living Alone” by Jim Shepard

Jim Shepard was first published in Electric Literature back when we had a print magazine, in our first issue in 2009. That story, “Your Fate Hurtles Down at You,” won the PEN/O Henry Prize. Five years later, Shepard returned with another deeply-researched masterpiece, about a doomed lookout platform in the Atlantic ocean. Though the story was original to Recommended Reading, we invited Joshua Ferris, author of To Rise Again at a Decent Hour, to write the introduction.

“The basic facts of the case are pretty simple,” Ferris writes, “the United States Air Force, believing it required more time to detect and defend against a Soviet invasion, ordered radar towers erected in the Atlantic Ocean, one of which, Texas Tower 4, capsized in 1961 and sank to the bottom of the sea. Twenty-eight airmen and civilian contractors were killed…In an economical ten-thousand words, he introduces us in this story to no fewer than eight substantial characters and a few colorful others caught up in the tragedy of Texas Tower 4. He gives them jokes and arguments and painful phone calls. Throughout his retelling, we see a fruitless accumulation of missed opportunities and final warnings and private ultimatums. Shepard points these out one by one. As the wind and the waves chip away at the foundation and support of Texas Tower 4, we see how wronged the men are, and how doomed.”

“The Soul is Not a Smithy” by David Foster Wallace

David Foster Wallace’s “The Soul is Not a Smithy” was first published in AGNI in 2003, and later collected in Oblivion. The story is about a classroom shooting of the kind only Wallace could write, and mixes together fantasy, paranoia, and harrowing violence.

In his introduction, AGNI editor Sven Birkerts reflected on what it was like to receive a “submission” from Wallace, who by then was already a literary icon.

“I knew the Wallace legend, knew what writers as well as readers thought of him; knew, too, that he was at a place in his career ascent where he could have put almost anything he wrote right into the pages of Esquire, Harper’s, The Paris Review. And here I was — by this point I was palming it, weighing it, looking to see how many pages it ran — holding a new long story. I hadn’t read a word, but I was already imagining the typewritten pages converted to font, reading the title ‘The Soul is Not a Smithy’ in bold… I indulged myself this way because I knew Wallace enough — from meeting him, from reputation — to know that there was no writer out there who was harder on himself, who was less likely than he to send out work before its time. And I had read the man’s work. I knew the level at which I admired it.”

“The Moon In Its Flight” by Gilbert Sorrentino

Gilbert Sorrentino is one of the literary luminaries that might be called a “writer’s writer,” that double-edged compliment that means the writer is immensely respected and talented, but not famous. A former editor at Grove Press, friend to William Carlos Williams, and the author of over 30 books, such as Mulligan Stew and Little Casino, yet his name doesn’t ring the bell with readers today.

Jenny Offil, author of Dept. Of Speculation and the forthcoming Weather, selected this story from Sorrentio’s eponymous 2004 collection for Recommended Reading. “When I finished it,” Offil writes, “I just sat there, thinking, Holy shit, holy shit, holy shit…I had never read a story that contained so much emotion in so little space. It swings from the most stunningly cynical moments to the most unnervingly tender, often within the space of one paragraph. And like all geniuses, Sorrentino makes it look easy. I will never write something as good as this story, but I like rereading it, seeing again how high he set the bar. Believe me when I say I wanted to kiss his shoe.”

For further reading, check out “The Pride of Life” by Gilbert’s son, Christopher Sorrentino, recommended by Joanna Yas.

2015

“Lady of the House of Love” by Angela Carter

British writer Angela Carter, the author of nine novels and four short story collections, was a pioneer of feminist magical realism. Kelly Link wrote the introduction for the anniversary edition of her beloved collection, The Bloody Chamber, published on what would have been Carter’s 75th birthday. From that collection, Link selected “The Lady of the House of Love,” and expanded on her thoughts on the story for Recommended Reading:

“I love ‘The Lady of the House of Love’ for the luster of Carter’s language; the tensile strength of the prose; its luscious, comical, fizzing theatricality. The handsome and wholesome boy on the bike, the decayed wedding dress, the bird in the cage, and the countess herself, who would like to be in a different kind of story from the one in which she eats rabbits and men…Of course, if you are brave enough and good-hearted and do not realize you have stumbled into a vampire story, you might escape. In a fairy tale, innocence is a key that opens a door through which you can flee — without ever realizing that you were in any danger. (Experience is another key entirely.) In the real world, of course, there are worse things than vampires…Carter gives us all the trappings of the gothic, the vampire narrative, and then briskly, explicitly dismantles the gothic stagecraft the next morning.”

“The Swan as Metaphor for Love” by Amelia Gray

“The Swan as a Metaphor for Love,” a pithy story about exactly what the title suggests, was first published in Joyland and later collected in Gutshot. Lisa Locasio, author of Open Me and the former editor of Joyland walks the reader through the pleasures of Gray’s prose in her introduction. “Sometimes, trying to identify what, exactly, makes a piece of writing work is quite difficult,” Locasio writes, “which is why people like me make the foolhardy decision to dedicate their lives to the study and production of literature. Other times, a piece’s magic is so obvious that it becomes performative, incantatory, almost beyond interpretation. Amelia Gray’s ‘The Swan as Metaphor for Love’ falls in the latter category. There’s a word for what makes this story so good — diction — but to reduce its power to a literary term seems to me a missing of the point. What I really want to draw your attention to is the better-than-it-has-any-right-to-be phrase ‘some fuck teenager,’ which appears in the parenthetical aside that is the story’s third paragraph. How I admire this some fuck teenager and the ‘half a can of beer’ he or she has contributed to the pond scum Gray describes. How I have agonized over the source of his or her power.”

Steph Opitz selected Gray’s “These Are Fables” for RR in 2013. Gray’s latest novel, Isadora, was published in 2016.

“Stone Animals” by Kelly Link

Kelly Link is the author of the short story collections Stranger Things Happen, Magic for Beginners, Pretty Monsters, and Get in Trouble, which was a finalist for the 2006 Pulitzer Prize. Lincoln Michel, the former editor-in-chief of electricliterature.com, selected “Stone Animals” from Magic for Beginners for Recommended Reading.

Michel writes, “Like most of her stories, ‘Stone Animals’ is hard to classify yet impossible to forget. It’s a ghost story without any ghosts, domestic realism in which the domestic is unreal. Ostensibly, ‘Stone Animals’ follows a husband, a pregnant wife, and their two children as they settle into a new house in the suburbs. And yet. ‘Stone Animals’ is brimming with Gothic terror and uncanny unease. If the house is haunted, the haunting is not found in grand, Gothic architecture or secret chambers. The haunting is in the banal objects of everyday life. The TV, the car, even bars of soap. What entities are haunting or what this haunting entails, is, like so much else, unclear.

“‘Stone Animals’ is thick with meaning — psychoanalytically inclined readers can have a field day — yet resistant to simple interpretation. The story transforms as you look at it, in the same way that Link’s fiction expertly moves between genres and resists simple forms.”

“You’re Home Early” by Vincent Scarpa

Vincent Scarpa’s “You’re Home Early” is a story with astounding emotional complexities,” writes Halimah Marcus in her introduction. “Annie, a divorced orthodontist from Chicago, travels to visit her father on death row at the Huntsville Prison in Texas the day before his scheduled execution. This situation is beyond the average person’s capacity for imagining, let alone empathy, but Scarpa somehow manages to do both. Annie herself is unable to conceive of her own situation; she tells her staff and her few friends that she will be out of town at a dentistry conference. No one knows where she really is or what she is doing. Her reasons for making the trip are mysterious even to her: ‘It may be as simple as she is lonely and curious and wants to be there for the end of the story that has tailored the entirety of her life,’ Scarpa writes. ‘It may be as complicated as because he asked her to.’

“As she visits the prison, Annie struggles to find a rubric for her feelings. Years ago her father committed a gruesome, sadistic murder, and as a result his life and his death will take place on the very edge of society, so far outside Annie’s normal life — of anyone’s normal life — that her grief becomes uncanny.”

Scarpa’s short stories have also been published widely and his he has interviewed many authors for Electric Lit. Those conversations can be found here.

2016

“The Great Silence” by Ted Chiang

Ted Chiang is the contemporary master of thoughtful, empathetic science fiction that thrills fans of hard scifi as much as it does literary snobs dabbling in genre. His most recent collection, Exhalation, was on practically every year-end best list, including ours.

Karen Joy Fowler is the author of three short story collections and six novels including The New York Times best-seller The Jane Austen Book Club and, most recently, We Are Completely Beside Ourselves. She recommended this story in her capacity as the editor of 2016 edition of Best American Science Fiction & Fantasy, in which it was included.

“As any long-time reader of science fiction can tell you,” Fowler writes, “‘The Great Silence’ is another name for the Fermi Paradox, and the Fermi Paradox is a meditation on two contradictory truths: 1) the idea that we represent the only intelligence in the universe is preposterous and 2) despite the increasing range of our extraterrestrial search, we have found only silence.

“Ted Chiang’s very short story, ‘The Great Silence’ adds another set of questions to these speculations. Why, he asks, are we so interested in finding intelligence in the stars and so deaf to the many species who manifest it here on earth?”

“If That’s All There Is” by Mona Awad

Laura Van den Berg, the author of The Third Hotel, the forthcoming collection, I Hold the Wolf by Its Ears, and, most importantly, another story on this list, wrote the introduction to Mona Awad’s “If That’s All There Is.” The story is from Awad’s “gutsy and glorious debut,” Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Fat Girl. In it, Van den Berg explains, “the narrator is the recipient of a dubious overture from her co-worker, Archibald. She contemplates his offer and decides — though it is a decision saddled with ambiguity — to take hold of the door he has shaken loose and pull it open a little wider.

“‘If That’s All There Is’ is, of course, about so much more than the relationship between the narrator and Archibald; its complexities of subject are manifold. It is about the sometimes unfathomable insanity of attraction. It is about the daily, deadly concessions women so often make. That ruinous compulsion to accommodate. It is about the way the most unlikely person can have the power to make us, for a moment, feel at home in our own skin — even if, at the same time, they are contributing to our unraveling. This story, like much of Awad’s fiction, is also discomfitingly hilarious: ‘This bland man is licking the crotch of my underwear, how nice,’ the narrator thinks during a very awkward cab ride.”

Mona Award’s novel Bunny was included on Electric Lit’s list of the best novels of 2019.

“The Bastard” by Patrick DeWitt

In her introduction, Recommended Reading editor-in-chief Halimah Marcus writes, “Before launching Recommended Reading in 2012, Electric Literature published a quarterly anthology — five stories in each issue, available in print as well as eBooks. We had the privilege of publishing this short story by acclaimed novelist Patrick DeWitt in one of those volumes. ‘The Bastard,’ which is uncollected and previously unavailable online, is reprinted here.

“The Bastard is a con man, motivated by money and bragging rights, becoming whoever he needs to be as a means to those ends. Confidence, intuition, and research are a con man’s specialties, and indeed when the Bastard shows up to Farmer Wilson’s door he is armed with all those things, plus information, whiskey, and charm. These are materials of a masterful storyteller, and though you’ll have to bring your own whiskey, DeWitt is equally armed. With his assured, ventriloquist prose, DeWitt is a kind of law-abiding con man, able to convince us, on a basic gut level, of outlandish scenarios and outsized personalities.”

Patrick DeWitt is the author of the novels Ablutions, The Sisters Brothers, which was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize, Undermajordomo Minor, and, most recently, French Exit. He does not often write short stories.

“To Revive a Person Is No Slight Thing” by Diane Williams

Deb Olin Unferth selected this story by another master of minimalism, Diane Williams.

In her introduction, Unferth writes, “This small quiet story is of a woman putting together an average dinner and eating with her husband. But Williams is expert at turning the calm and ordinary into the classical: the private surprise that one has found oneself in a fresh life, sitting with a ‘new spouse’ (a phrase that implies both newness and familiarity). I read this and I feel the drums thrumming, the effort of revival, of coming back to life, after God-knows-what. Not in a dramatic way — not snakes and tongues, roll away the rock — but in the simplest, smallest, most beautiful manner: ‘How unlikely it was that our home was alight and that the dinner meal was served.’”

Read the title story of Unferth’s most recent collection, Wait Til You See Me Dance, in Recommended Reading.

2017

“Black-Eyed Women” by Viet Thanh Nguyen

Viet Thanh Ngyuen is the author of the Pulitzer-prize-winning novel The Sympathizer as well as two other works of nonfiction. A version of “Black-Eyed Women” was originally published in Epoch and later collected in The Refugees. In his introduction to the story, Akhil Sharma writes: “Viet Thanh Nguyen writes funny. ‘Black-Eyed Women’ begins with the many unpleasant ways that one can become famous: sex scandal, being kidnapped and held prisoner for many years; surviving what should kill one. And after this list, we meet the narrator, whose profession is to ghostwrite autobiographies of people who have endured such things. (Laugh piled on unexpected laugh.) And then the ghost writer complains about not being acknowledged for her work (as if a reasonable person would want such a thing), and her mother steps in and begins mocking in the way that immigrant mothers can.”

“If You Sing Like That For Me” by Akhil Sharma

In her introduction to Akhil Sharma’s short story about a recently married woman and her husband, excerpted from If You Sing Like That For Me, Yiyun Li celebrates Sharma’s abilities as a writer from the first line, all the way up to the last one. She asks: “What distinguishes a great story writer from a mediocre one? Akhil Sharma would be among the few living authors I would choose, along with masters like Chekhov, William Trevor, Eudora Welty, and James Alan McPherson, to tackle that question.

“It’s not what a writer gives a character and then takes away that makes a good story — we have all learned to live with, and oftentimes become indifferent to, other people’s losses. But six months from reading the story I may wake up one morning, to a raining day or a snowing day, in my own house or in a hotel room, feeling the devastation that runs through Anita, [the protagonist] at the end of the story. No words prepare us for grief.”

“The Glass That Laughed” by Dashiell Hammett

Dashiell Hammett is the master of Hardboiled Detective Fiction. “The Glass that Laughed” was originally published in 1925 and later collected in The Great Ops, co-edited by his granddaugther, Julie M. Rivett, and Richard Layman.

In their introduction to the story, Layman and Rivett write, “In this short, psychological thriller, a man struggles with guilt after murdering his twin brother. The protagonist sees his dead twin’s face in every mirror, and quickly loses himself to paranoia and grief. Hammett, master of detective fiction, creates an eerie, uneasy atmosphere in this previously-unpublished story.”

They also explain that the story was discovered because a fan posted on Facebook, saying he had discovered an uncollected Hammett story in the November 1925 issue of True Police Stories, which was published between May 1924 and April 1926 by “organ of the New York Police Department.”

“Sundays” by Emma Eisenberg

Emma Eisenberg is the author of The Third Rainbow Girl, forthcoming from Hachette Books in 2020. In her introduction to this original short story, Halimah Marcus contemplates the narrator, whose life is framed by sex six days a week, with six different people: “Eisenberg’s narrator is confident yet reflective; she is assured in what she wants and understands what it requires of her, and of others. She describes her ‘way of living’ as ‘not for the faint of heart,’ as requiring ‘vain and detail-oriented work.’ ‘Is this too much desire?’ she asks rhetorically. ‘The world says yes, but I say no.’ Her schedule is accompanied by a meditation on what she describes beautifully as ‘bothness,’ which leads to an understanding of herself that is bittersweet and profound.

“‘Sundays’ is a story for which it feels imperative to read every word, and that rewards second and third readings. Eisenberg writes like Grace Paley for 2017, with sentences that are at once compact and airy, assertions that are also questions, and politics that are radical yet tenderly cultivated.”

2018

“Someone Is Recording” by Lynn Coady

Lynn Coady is the author of six books of fiction, including the short story collection Hellgoing and The Antagonist. Her latest novel Watching You Without Me is forthcoming from Knopf in 2020. This original short story “Someone Is Recording” remains one of the most-read issues of Recommended Reading to date.

In her introduction, Halimah Marcus sets the scene: “Gary, a middle-aged professor, gains unwanted scrutiny when his ex, Erica, takes her grievances about their decade-old relationship online, where she is particularly skilled at skewering Gary’s behavior to her growing cache of followers. From what the reader can gather from the one-sided correspondence — Gary emails, Erica doesn’t respond — Gary vengefully badmouthed Erica to their mutual mentor back when he was her TA. But the details, as represented by Gary, are murky. What had he done to make her wrath still so fresh, 15 years later?

“Like any great satire, ‘Someone is Recording’ is deft in its critique, brilliant at forcing the reader to make unwitting assumptions. Depending on the direction of those assumptions, some readers will find their own behavior justified, others will find it called into question. That latter reaction, which I hope every reader will embrace, makes for a superbly discomfiting read.”

For more Coady: read “The Drain.”

“Last Night” by Laura van den Berg

Laura van den Berg was first published in Recommended Reading in 2014, with the story “Where We Must Be.”

In this original story, “Last Night,” (which will be included in van den Berg’s forthcoming collection I Had a Wolf by the Ears in 2020 from FSG), Halimah Marcus writes: “youth and suicide are intertwined: short-sighted, obstinate, dangerous. The narrator, now closer to sixty ‘than to the girl who stood on those tracks, on her last night, thinking about trains,’ tells her story with a kind of regret-tinged nostalgia akin to survivor’s guilt. Here, as in her sensational new novel, The Third Hotel, Laura van den Berg writes a woman who is isolated yet open, who is grieving but who possesses a worldview punctuated with dry wit. Longtime readers of van den Berg’s know never to miss a word she writes, and with this story, newcomers to her work will be likewise entranced.”

“A Strange Tale From Down by the River” by Banana Yoshimoto

“A Strange Tale from Down by the River” was originally published in Japanese under the title Tokage in 1993 and then published by Grove Atlantic in the collection Lizard the same year. The story was selected for Recommended Reading by the co-founder of the Storyological Podcast, E.G. Cosh. The story, as he writes, “is, in part, a story about making peace with the flow of your life, with the decisions you make and the lives that you visit, but don’t settle into. It is a story that knows peace-making requires strength, and presence, and deeply engaging with yourself and what it means to change. I came away from Yoshimoto’s tale thinking about how change is really only possible when we allow fresh stories into our understanding of ourselves and others. About how joining a new family opens us up––to sharing stories, to hearing stories, and to the stories that we create together.”

“On the Town” by Helen Dewitt

Helen Dewitt’s story “On the Town” was published in her 2018 collection Some Trick. In her introduction for the story, Sheila Heti prepares the reader for what it means to enter into the world of a Helen Dewitt story: “You are about to read a comedic tale by the brilliant and inimitable Helen DeWitt, patron saint of anyone in the world who has to deal with the crap of those in power who do a terrible job with their power, and who make those who are under their power utterly miserable. She is also the patron saint of those who would like to do an honest day’s work, but can’t because of the stupidity of other people. How would a parable read if it expressed the fantasy that one simple man might swoop in and make order out of the chaos and stupidity of the world? Who would be Helen DeWitt’s Jesus Christ — making order from disorder and bringing joy to so many — who goes about his fixes in utter innocence and simplicity, and whose straightforward goodness triumphs over the complications of the world, untangling them?”

For further reading, try Dewitt’s “Recovery,” which was published in Recommended Reading in 2012.

2019

“Pussy Hounds” by Sarah Gerard

Sarah Gerard’s essay collection, Sunshine State, was a New York Times Editors’ Choice and her novel, Binary Star, a book-of–the year at NPR, Vanity Fair, and Buzzfeed. Her next novel True Love is forthcoming from Harper Books in 2020. In her introduction to this original short story, Halimah Marcus explains: “‘Pussy Hounds’ is a story about four friends who take a trip to Maine for a self-imposed writing retreat. As it happens, not much writing gets done. One of them isn’t even a writer to begin with. They go for walks, watch movies, gossip over dinner. Their delicate social accord is threatened by a mysterious ‘back massage incident’ that occurred years-prior. Nina, the narrator, has recently escaped a toxic marriage. Filtered through her inner life, the story is also about making art, gender and sexual identity, self harm, and abuse. ‘Pussy Hounds’ is not, despite the title, a story about chasing pussy, though pussy does play a part…The complex subjects that this story is “about” are brought in through the Trojan Horses of everyday life—pop culture, Instagrams, emails, amusing anecdotes. By the end, readers will be left wondering how a story about four women who like each other but also kind of don’t, who are attracted to each other but also kind of aren’t, can be about so much. How did Sarah Gerard sneak so much stuff in?”

“Predestination” by Trevor Shikaze

In Halimah Marcus’s introduction to Trevor Shikaze’s story, “Predestination,” she frames the context for this darkly comic story about death:

“There’s a New Yorker cartoon by Paul Noth in which God says, ‘Look, if I have to explain the meaning of existence, then it isn’t funny.’ The idea that all of life is a joke animates Trevor Shikaze’s ‘Predestination,’ a story about a man who knows he is about to die. If life is a joke then death delivers the punchline, and this story, which could easily be macabre, is somehow full of laughs. In the world of ‘Predestination,’ the Engine accurately predicts when people will die, but it’s the way you die, which remains unknown, that ties up all the loose threads and reveals the ‘meaning’ for your existence.”

“The Daddy Thing” by KC Mead-Brewer

K.C. Mead-Brewer is a graduate of The Clarion Writers’ Workshop, and her fiction has been nominated for Best Micro Fictions, Best Small Fictions, and a Pushcart Prize. When recommending her story “The Daddy Thing,” editor-in-chief Halimah Marcus wrote: “Mead-Brewer has written a modern fairy tale of the highest literary merit. Like the witch that cages children, or the wolf that swallows the grandma, the brutality of ‘The Daddy Thing’ is at once laid bare and cleverly disguised. It makes sense: in life, violence is permanent; but in fairy tales, violence is reversible. The children escape the cage, the grandma is preserved in the wolf’s stomach. In ‘The Daddy Thing’ the violence is spectral, hidden, yet pervasive. Waiting to be appeased. And like the best fairy tales, it is far too scary for children.”

“A Full-Service Shelter” by Amy Hempel

“A Full-Service Shelter” was originally published in Tin House, and later collected in Sing To It. Rick Moody, a friend of Hempel’s, wrote in his introduction to the story that “Full-Service” is a direct response to Leonard Michael’s story “In the Fifties.” But “A Full-Service Shelter” is also distinctly an Amy Hempel story, as Moody describes:

“A Full-Service Shelter,” like many other stories by Amy Hempel, manages to both create a possibility for reasonable perception of our time here, and recoils from the brutality and instability that is everywhere around us. Having watched the author read the work, having watched and heard it read, I can say that I believe it must be immensely difficult to feel everything that my friend Amy Hempel feels and gets down on the page. It must be hard to write from this place. But also I feel so lucky to be alive while there is someone who can write a story like this. You are now going to feel that way, too.”