Interviews

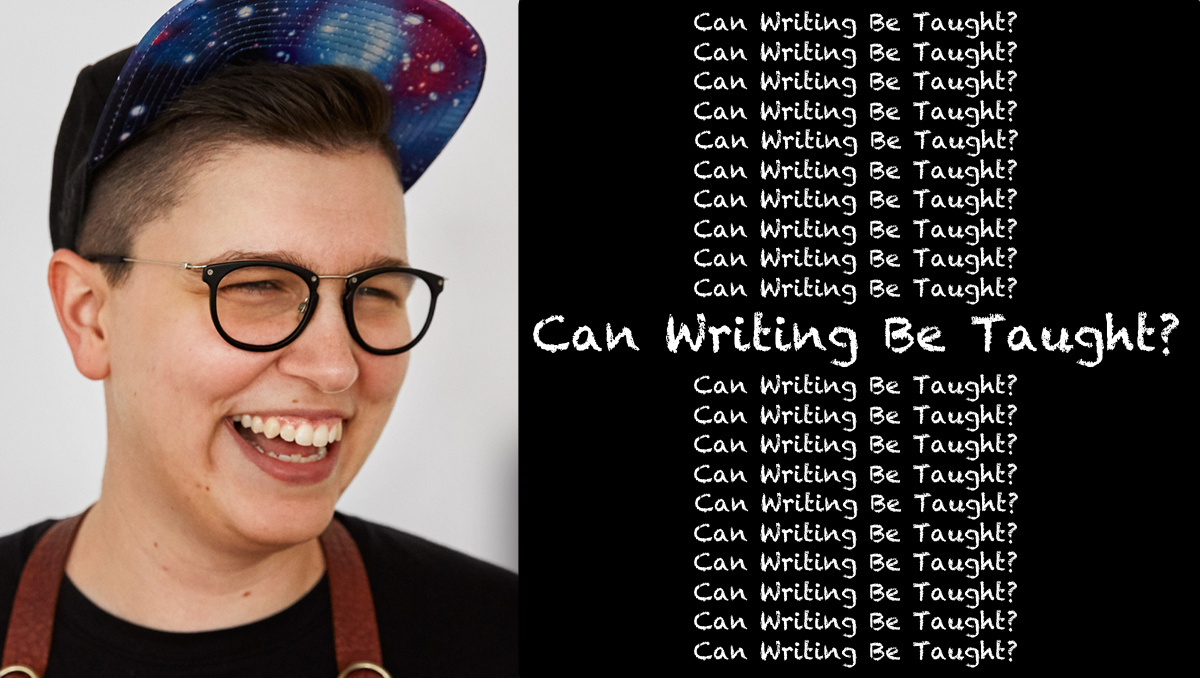

A.E. Osworth Thinks You Should Go Ahead and Eat a Tuna Melt in Class

Ten questions about how to teach writing with joy, confidence, and Doritos

In our series “Can Writing Be Taught?” we partner with Catapult to ask their course instructors all our burning questions about the process of teaching writing. This month, we’re talking to A.E. Osworth, New School instructor and author of the forthcoming We Are Watching Eliza Bright, who’s teaching a class about something notably rare and precious these days: joy. Osworth’s class on “joy-first drafting” helps writers break free of the over-structuring and self-seriousness that sometimes hinders creativity, so we were excited to get their thoughts on how they maintain that sense of delight through their teaching.

What’s the best thing you’ve ever gotten out of a writing class or workshop as a student?

I have a lot of best things; my identity as a writer and my process have been deeply impacted by the act of workshopping and being in community with writers there-in. I could talk for days on the things workshop has given me and I will try to stick to the highlight reel. My first novel, We Are Watching Eliza Bright (forthcoming from Grand Central in April 2021) actually started as a two-page literature seminar assignment in Shelley Jackson’s class at The New School, where I got my MFA. If we take “thing” as literal, that’s the best “thing.” But I’m also grateful for all the concepts I’ve learned as part of workshop—a lot of my pedagogical framework is based off things I learned from Tiphanie Yanique, who mentored my teaching as well as my writing. Helen Schulman gave me The Ninety-Ten Rule (you will discount ninety percent of what you hear in workshop and act on ten percent of it) to keep us all from our desire to please our peers and workshop leaders. Just this last January, Namwali Serpell introduced me to asking for “wild speculation” in workshop as a tool to reflect the groundwork an author has already laid out but is not yet aware of. Ugh, so many things! Workshop is such a gift.

What’s the worst thing you’ve ever gotten out of a writing class or workshop as a student?

I’ve rarely been in a workshop where I couldn’t find something of value, but one time I did rewrite some sections of my book because the professor and a fellow student thought I should be nicer to cops in my fiction—I really did not trust my taste, my skill or my moral compass at the time. Don’t worry, all those parts are changed back now.

What is the lesson or piece of writing advice you return to most as an instructor?

Potters can’t make something without any clay; first drafts are the ‘clay’ of writing. Formless, messy.

I really do remind my students (and myself) often that all first drafts are shitty. Potters can’t make something without any clay; first drafts are the “clay” of writing. Formless, messy. They’re the raw material.

Does everyone “have a novel in them”?

You know, I have no idea because I don’t think it’s a valuable lens through which to consider writing! It doesn’t actually matter if an individual has a novel in them; it matters if they’re able to get it out of them. I mean that in the normie personal discipline way—do you sit down and write it? Do you do that every chance you get?—and also in a structural justice way. Who has the opportunity, the unstructured time, to sit down and write? Who is able to partake in the world of traditional publishing and who is being impacted by bias, and at which stages? Mostly I don’t care if everyone has a novel inside them, but I deeply care that we as writers and readers do our best in making sure that if someone stumbles upon a novel in them, they have the tools and time to get it out of their body where it belongs.

Would you ever encourage a student to give up writing? Under what circumstances?

My original answer was no, but upon reflection I do think I would encourage a student to quit if they were using writing as self-harm in some way. Storytelling is one of the things I value the highest in this life and, even then, it should never cost someone their happiness and sanity.

What’s more valuable in a workshop, praise or criticism?

Given the workshops I’ve taken, I feel like my take is hot: praise. Infinitely more valuable, especially when workshopping first or early drafts. If a workshop identifies what is working or electric and an author is given the encouragement to write and edit toward those things, most of what’s “not working” falls away.

Should students write with publication in mind? Why or why not?

You can’t be an artist without people’s interaction with your work, and that interaction is thrilling magic.

I feel like there are two things this could mean, and one of them I strongly like and the other I strongly dislike. I don’t think students, or any author really, should chase what they think is “publishable.” The recent past means nothing anyway (things are always changing!) and you can’t write to trends unless your heart just happens to be really into whatever the world is fashionably loving at the moment. But the other way to take this is to remember that books are for readers the same way music is for listeners, plays are for audiences. You can’t be an artist without people’s interaction with your work, and that interaction is thrilling magic. Trust your readers and treat them well as you write. Remember that every reader will read your text differently than you thought they would, and differently from each other. As a writer, you are building a jungle gym and readers will play on it however they play on it. Give them fun brain shit to do.

In one or two sentences, what’s your opinion of these writing maxims?

- Kill your darlings: Great advice—not everything you love will work for the story you wind up telling. But if your darling includes your only gay or trans character and killing them means either taking them out or their death in the plot, think real hard about why they’re the only one and why they have to die.

- Show don’t tell: Great advice—but not everything in the story weighs the same. Help guide a reader to the buried gold by not over-describing the dirt and the shovel.

- Write what you know: Great advice—writing what you know is a one way to cut down on your research time and make sure you’re staying in your lane. But it’s not particularly brave or particularly sustainable; write toward what you want to know as well, accept that you will fuck several somethings up royally and ask questions with a beginner’s mind.

- Character is plot: I’ve actually never heard this one before and had no idea it was a maxim! But given what I think it means, why stop there? Everything is everything—all the elements of the story are playing in concert to create one joyous, glorious whole.

What’s the best hobby for writers?

Anything that brings you joy; anything that brings you into a community you love.

What’s the best workshop snack?

Normally I would say anything without a smell or a crunching sound but it’s pandemia—you are in your own home and you can mute your mic, rock on with your tuna melt and your Doritos.