interviews

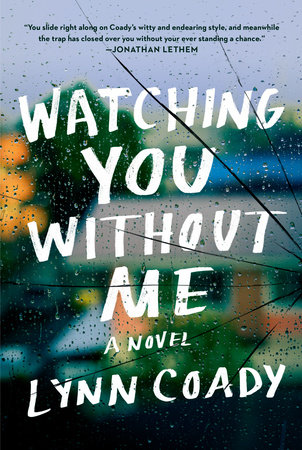

Can You Care for Others Without Destroying Yourself?

Lynn Coady, author of "Watching You Without Me," on martyrdom, middle-aged women, and caregiving

Women providing care––and the ways in which care can be made murky by expectations related to gender, religion, and tied unfairly at times to a means of proving love—is a significant theme in Lynn Coady’s latest novel, Watching You Without Me.

After Karen’s mother Irene passes away, Karen returns to her childhood home in order to process the complicated relationship she had with her mother, sift through the detritus of her former life, and make decisions about how best to support her sister Kelli, who is disabled. These reckonings lead to questions, both for Karen and the reader: How much can –– and should –– we care for others without losing ourselves in the process? What happens when caregivers burn out? What lines can and should exist between caregivers and the people they care for, and what harms are caused when these lines are blurred?

In our current climate, one in which women are shouldering childcare duties while also attempting to maintain work (spoiler: it’s impossible), and parents are being told they are no longer allowed to care for children at home while they work (a policy arguably disproportionately affecting women), Coady’s book, one unapologetically written about women’s lives, for women, serves both as a balm and guide. And while the characters do grapple with significant issues related to self-preservation and complicated familial relationships, there’s also a compelling note of tension that rises to crescendo, rendering this a deliciously layered read.

Over the phone, I spoke with Lynn Coady about the link between gender and guilt, the significance of writing for women, care as a practice, and the ways in which silence can be insidious.

Jacqueline Alnes: A big theme in the novel is caregiving. Care as a practice often seems gendered, at least historically, and the women in this book struggle with feelings of guilt when they choose to ensure their own wellbeing over providing for others. What was important to you when writing about care?

Lynn Coady: I wanted to underscore the generational difference between Karen and Irene. They are only one generation removed, but there is this influx of feminist thought that has taken place and it has opened up a huge chasm. In a way, Irene is a woman with one foot in the past—in women’s pasts, with all of the stereotypes, misogyny, and circumscribed roles that that implied—whereas Karen is a person with her foot in the future. Karen is a product of feminism and a supposedly more progressive society.

I think the crucial difference between them, if I were to boil it down to one idea, is Irene comes from a generation that thinks it’s one hundred percent good for a woman to completely devote her life to the care of others as opposed Karen’s generation, which believes in a woman needing balance in her life, a woman looking out for herself first.

JA: There is an interesting line that links Irene’s caregiving to faith:

It was like faith. It was exactly like faith in that you had to stop futzing around and let it take you over…it was a small world, a circumscribed world, but it was your world and you did what you could to make it beautiful.

There is a thread of religion throughout, and ideas of martyrdom. Religion also seems to offer a way for the characters to find beauty. How do you see religion or faith and caregiving intersecting?

LC: Catholicism is such a significant influence on Irene’s thinking. She comes from a very sexist world but also a Catholic tradition, which really teaches women the best thing they can do is to devote themselves to the care of others. Irene, as many women do, believed she could get a sense of purpose and satisfaction through care.

JA: That makes a lot of sense. One other scene related to religion is one where Irene wants to join choir but she is in the front row with her two daughters so she is viscerally stuck; she can’t get up to sing because she can’t leave them. I felt like it was such an interesting metaphor for voicelessness or the constraints of motherhood.

LC: She’s stuck and she’s looking for ways to express herself that are allowed to her. She can tell herself that singing in the choir is another form of service. She’s participating in her church; she’s praising the Lord in song. Irene has the right to her own pleasure, but she doesn’t allow herself to go after what she wants unless she can justify it through the lens of what is good and holy.

JA: Ah, I hadn’t considered it that way. You mention in the afterword that you researched a lot about caregiving and there’s a lot in the book where we learn about some of the faults within the system. What did you find while researching that interested you?

LC: I knew a bit about social services going into it because I had a student job with social services and children’s aid in Nova Scotia when I was in my 20s, and I knew that people will report other people if they think they’re not looking after their children, or if they think their elderly parents or dependents aren’t being cared for. But the big thing I learned was that these caregiving organizations didn’t have any kind of government regulation or oversight, and that blew my mind.

JA: The lack of oversight almost makes Irene’s obsession with caring for Kelli herself more understandable. If the system is not regulated, then you don’t know who’s coming to care for your loved one.

LC: Yes. What happens with Karen—and I think this happens with a lot of people—is that if someone is struggling and social services are alerted, that can be really bad, but also it can be a point of finding help. When the social worker arrives, you realize that you have resources you can rely on. But entering into that system and negotiating that system and talking to various offices is daunting.

JA: And learning the language of it too.

LC: Exactly.

JA: If you don’t know what to ask for, how are you supposed to have the language for it?

LC: Yeah, and if you feel like there’s a threat of your loved one being taken away because you don’t know how to negotiate that system, that can be really intimidating.

JA: In thinking about women and voices, there are quite a few scenes of women choosing to speak out or not and that affecting them in significant ways. In some instances in the novel, women protect other people with their silence. Society, in many ways, conditions women to be polite or quiet—what about that interests you?

I just said fuck it, I’m just going to write something for women. All about women. I don’t care if male readers are into it or not.

LC: I think what interests me about it is the instinct of it. It’s a thing that we all have been taught—not overtly, but we have absorbed through osmosis our entire lives. As I was writing the book, I was interested in the way Karen instinctively negotiated Trevor, who is one of Kelli’s caregivers. It wasn’t something I sat down and intended necessarily, but I was just putting Karen in these situations where Trevor seems a little bit annoyed or Trevor seems a little bit disapproving or he was pushing her in some way or he was being a little bit hostile. Karen would always deke off to the side a little bit. She always had a move that was never overtly pushing back. Instead, she’d intuit what he needed to hear and she would do that. Karen is instinctively negotiating Trevor’s moods and his potential anger.

I think that’s something women do. I don’t know if this happens to you, but every once in a while I’ll be talking to a man who is in a position of authority and my voice will be high. I’m like, why did I pitch my voice to this level? What’s going on? And I realize I’m talking a couple octaves higher than I usually do. I realize I’m making myself smaller, in a way, or making my voice sound more innocent or softer.

JA: I start my orders at restaurants with “I’m sorry, could I have…” and my friends always remind me that I can just ask. I don’t have to apologize for asking for a drink.

LC: Right, you don’t have to apologize.

JA: Within the book, there are allusions to future listeners. For example, Karen says she shakes her head “along with all the people I tell this story to.” There seems to be power there, in that Karen has survived this ordeal and can tell her narrative how she chooses. And of course, this exists within the larger frame of the novel, which is also a story being told. What, for you, is the power of story?

LC: I’m always preoccupied with the question of why a given narrator is telling a story. I always find that I need to know before I write, even if it’s a third-person narrator. I need to have some rationale for why a particular story is being told by someone. What’s the subjectivity at play here? With Karen, I feel like what I wanted to get across was that she’s talking about a time in her life that was really difficult and where she made some of the biggest mistakes of her life. We get the sense that she has told and retold this story. It’s been a dinner party anecdote and something she’s talked about with friends and I’m sure she has a million versions of it—a really short one, a long one, one she tells potential lovers.

I think ultimately she realizes that the reason she’s been telling this story over and over and over again is because she still hasn’t learned the lessons she should have learned, so this novel is her telling the story to herself. She’s going through it in ruthless detail and examines all of her flaws and misapprehensions and asks herself: should I hate myself for letting all that happen as much as I do?

When she gets to the end of that story, having told the story in this way has been a process of forgiving herself for that period of her life.

JA: Guilt comes up again. Her mother experiences guilt, she experiences guilt, and both of them for things that honestly they shouldn’t feel bad about. That also seems gendered.

LC: Very much so. Guilt is huge. It is a gendered guilt. Karen learned from Irene that women are supposed to live a certain way and want certain things, and if they don’t look after their loved ones in the prescribed way, then they’re not doing womanhood right. Trevor comes along and completely underlines all that. He affirms that Karen isn’t doing womanhood right, and insinuates that she has let everyone down. He plays on all these subconscious fears that Karen has. It’s very gendered and it’s also Catholic at the same time.

JA: This novel contains so many smaller insidious moments that seem like they hold potential for violence or harm of some sort to happen. Was there something about our current climate that was an impetus for you to write this book?

LC: I started writing this book in 2016, so before #MeToo got started, but even then there was something in the air. A lot of my books before this have had male protagonists. I have always felt like my books have had a feminist perspective but I was being sly about it. It was fun to try to write these male characters in male worlds as a feminist; showing the effects of patriarchy on men is one of the things I like to do. But when I sat down to write this book, I just said fuck it, I’m just going to write something for women. All about women. Women at middle-age, when you sort of deal with all your shit and look at the shit you’ve been through. I just had the feeling that this book is about women. I don’t care if male readers are into it or not.

JA: I thought you did such valuable work with Trevor in that aspect. After I read, I found myself going back to the beginning, at least in my mind, and remembering that he seemed so harmless. At the end, it escalates. Trevor obviously has issues, but he’s also part of this patriarchal society, and the ways he expresses himself, through anger, are the ways that men are often trained to express their emotions.

LC: I appreciate you saying that. People have said to me that as soon as you meet Trevor, you know something really bad is going to happen. I think he’s a little off from the start, but I’ve known so many men like Trevor who have the attitudes that they do and behave in harmful ways, but don’t become psycho stalkers. They are who they are. On some level, they are healthy, the way Trevor sometimes can be. Trevor wants to help and he’s kind of a goofball—in some ways, he’s a very typical guy.

JA: And he’s a caregiver, which is something that has not always been considered “masculine.” In the novel, Jessica brings up that Trevor caring for Kelli is strange because male caregivers often aren’t paired with female clients.

LC: I thought it was interesting to think about how Trevor performs masculinity in this role—caregiver—that’s not coded as masculine. His way of caring for people is being pushy and bullying them.

JA: Was there anything you read throughout this process that helped inform your process of writing?

It takes decades for women to shake off all the bullshit social conditioning they get and start to feel like confident, competent human beings.

LC: I used an epigram from Alice Munro at the beginning of the book and I was reading a lot of her work at the time just because the way she writes about women’s lives is so inspiring. She does not give a shit. She writes what she wants to write. I posted a thing on Twitter recently, it was just a joke piece listing all the one-star reviews for Alice Munro on Amazon. They were hilarious because they were totally true. People were saying things like “Ugh, it’s just a boring story about another Canadian woman’s life, or somebody else said that “nothing ever happens” in her stories. And it’s like yeah, that’s Alice Munro—she writes about “boring” women’s lives and they somehow feel so riveting and relevant and engaging.

JA: That relates what you mentioned earlier, too, when you said something like, “fuck it, I’m going to write a book for women.” There are interesting things happening in domestic spheres and there are complicated things happening for women.

LC: These stories are really human and crucial. It felt to me to write from the perspective of a middle-aged woman because, being at this age myself, I feel like it takes actual decades for women to shake off all the bullshit social conditioning they get and start to feel like confident, competent human beings who know their own minds and know their shit. But there’s always going to be a Trevor out there trying to undermine your confidence and make you feel small. At the same time, there’s also an element of disillusion that comes into play when you start to deeply understand how much of what you’ve been told and taught about yourself was garbage meant to keep you down. And it’s difficult to have to reckon, as Karen does, with the fact that you bought into all that garbage, and invested in it, for so much of your life.