interviews

A Woman Walks into a Bar…and Finds Freud

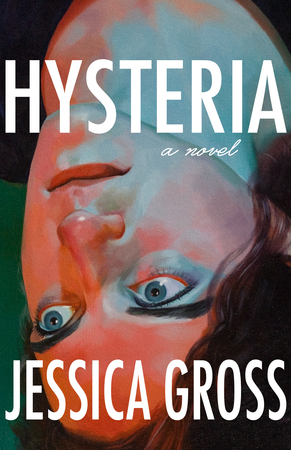

Jessica Gross's novel "Hysteria" is about a young woman's sexual exploration and self-destruction over the course of two nights

Plagued by a throbbing hangover, having just rendezvoused with her father’s colleague in her parent’s coat closet and then seducing her roommate’s brother home to bed, a woman walks into a dimly lit bar. “Dark and stormy,” she says. She is a woman who attempts to fill the ache of a void within her through sexual exploits, a woman who desperately desires her father’s affection, and serving her is no one other than Sigmund Freud, who is alive and well and mixing drinks in modern-day Brooklyn.

Hysteria, Jessica Gross’s debut novel, is in many ways a fever dream. Absurd at times, relatable in others, and threaded with darkness, the narrative takes place over a two day period, allowing for the reader to dive deep into the unnamed narrator’s complicated psyche. With rigid therapists for parents, a host of feelings she has been trained to repress, and a skewed perception of the world that makes her feel like she’s teetering on the edge of coming undone, the narrator careens through a variety of liaisons that leave her hungry for something she cannot find words for.

It is only when Freud (who might actually be Freud but also might be some strange projection the protagonist conjures in her time of need) presses his hands against her face that she is able to trace the root of her symptoms back to their origins, and even then her internal landscape remains shadowy, unknowable in ways. There is beauty in the ways in which Gross explores the complexities of her main character, allowing her carnal exploration while also laying bare the mechanisms that keep aspects of her emotional life contained.

Over the phone, Jessica Gross and I spoke about what it was like writing Freud into modern day; tensions between self-expression and restraint; and the power to be found in writing about sexual exploration from a woman’s perspective.

Jacqueline Alnes: Hysteria is a word that carries so much weight.

There is a really interesting tension between containment and liberation in the novel. In some parts, the main character has so much emotion she feels she can’t contain it, but outwardly she is just standing still snapping a rubber band against her wrist, saying calm down, calm down to herself while really she wants to run freely down the street. What was it like exploring that tension?

Jessica Gross: It felt very true to me. Many women I know, and also men, feel like certain emotions are okay to feel and others are not okay to feel. We’re told “be happier, be calmer, be cheerful, your pain is scary.” Many people are taught by their parents and the culture at large to corral feelings. With pain, I think it’s only by actually feeling it that people move through it.

JA: It’s funny to me that the main character’s parents are therapists, which is one of the spaces where you hope that you can express your full self or come with emotions and not be judged, but they almost seem like the people who are suppressing her in so many different ways.

JG: Totally. First of all, people can be adept therapists and not as good at being parents. But also, her parents are cognitive-behavioral therapists. I got the sense, both from friends and from the research I did for this book, that CBT is more concerned with symptom management than with deeply understanding the roots of and intricacies of the patient’s emotional life. For that reason, it made a kind of sense to me that the narrator’s parents would employ strategies to train her rather than offering empathy and sitting with whatever she was going through.

JA: I couldn’t stop reading once I started, and I finished late one night. The next morning, I wondered whether Freud in the book was real or not. I had the sensation that he was specific and tangible enough to be a real person, but also the main character had enough of an expanse in her emotional life to feel like she could have projected something like that.

JG: Oh, that’s so cool for me to hear. In the initial conception, he was real. He just appeared. Through revision, it became easier to read him as her delusion, but it was important to me that it never be definitively stated that that was the case. The book takes place so much in her head, and what is in her head is real to her, and thus to the book. And I also just love the idea of Freud appearing out of nowhere.

JA: The main character’s perception of reality is so warped at times that it’s like, well, if she thinks that way about events that have happened, then what else could she fictionalize?

JG: Exactly. Exactly.

JA: How did you get the idea for this book?

We’re told be happier, be calmer, be cheerful, your pain is scary.

JG: I’ve been in psychoanalysis for a long time, over a decade. When I was thinking about writing a novel, I knew I wanted to deal with psychoanalysis and Freud in some way. I can’t really track it—it’s like a gap in my memory —but I wrote in my journal sometime in early 2016: write a novel about Freud. And then, somehow, I started writing a book where Freud appeared in this character’s life.

JA: What was it like to write Freud into contemporary times?

JG: Oh, it was so much fun. Initially, I had the narrator going to Vienna. But then I visited Vienna, where my father’s family is from—they were Jewish, and fled in 1938—and was filled with antipathy; I found myself conflating modern-day Vienna and the past I knew about. I hated writing the novel in Vienna, and then I realized I didn’t have to: if Freud randomly and surreally appeared in the recent past, he could appear anywhere!

I started having a tremendous amount of fun. It ended up making so much more sense to me that Freud would appear in a bar in Brooklyn. He looks just like a hipster bartender, so why not?

JA: I loved that. There’s a level of absurdity, too, in finding Freud behind a bar.

The intimacy of waking up with her every morning and then rehashing every detail she could remember or not remember about the night before based on how much she drank was interesting because it kind of had almost this like elliptical feel. Reliving scenes made the novel feel more expansive in terms of time, if that makes sense.

JG: The way her mind works is so recursive that it’s almost like she’s living everything like 17 times over again.

JA: Your prose is so visceral and sensory. The narrator at one point describes the way people’s voices were being “drilled into the top” of her skull. And then the other voice was “sliding down my throat and through my chest and into my stomach where it made a red hot home,” which I loved. What do you consider when writing the body and sex?

JG: The example that you picked out is interesting because there are so many bodily essential details that aren’t sexual. I feel like writing the body is the best way to convey something on the page, even something intellectual. With this book, I wanted to immerse the reader in the narrator’s experience. I don’t want to tell the reader something, I want to induce the sensation in a way that it might feel in the body.

JA: Was it interesting to write the body in light of writing about Freud?

JG: In what sense?

JA: I’m thinking back to earlier in our conversation when you shared that one definition of hysteria is the way that emotions become visible or tangible in the body, like a symptom. Because you’re thinking so much about repression and sexuality, moments like the narrator tonguing the roof of her mouth hold a lot of weight.

Freud looks just like a hipster bartender.

JG: Psychoanalysis is such an intellectual endeavor, but often where it starts—at least in my experience—is with a physical feeling of something being wrong.

JG: That’s interesting. And then it also makes me think about what about the body is private and what is public in regard to your narrator. She has all these private, intimate moments with her body—some with other people, but mostly with herself.

JA: Yeah, she clearly has a very warped idea of how she appears to other people. Part of what I wanted to do with Hysteria was push the boundaries of acceptable discourse about sex. I think by now people are pretty comfortable hearing about women having sex, especially sort of disturbed sex. But discourse about women masturbating seems to have lagged behind. It was important to me, in my writing, to contribute to creating space for talking about that.

In the context of the book itself, what’s interesting is that she masturbates less because she’s aroused and more as a way of connecting to herself, and as a stress reduction technique. And the only time she comes is when she’s in private. She can’t permit herself to let go in front of a man, which was interesting to me too.

JG: In addition to Fleabag, I’ve seen comparisons of Hysteria to Otessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation, which resonated with me. What are books that you feel Hysteria is in conversation with?

JA: The book I thought about more than any other while I was writing was Portnoy’s Complaint. I read it in 2012 and I really loved it. I was excited by both the liberty Philip Roth took with writing sexual perversion and the way he dealt with psychoanalytic themes. Of course, Roth’s writing has been critiqued as misogynist; his narrators often objectify women. I was interested in inverting that. My narrator certainly doesn’t have a healthy relationship to her sexuality, I would say: I’m not condoning her objectification, which frankly hurts her more than anyone else. But because of the inversion of the power dynamic, it resonates differently, and in a way that excited me.