interviews

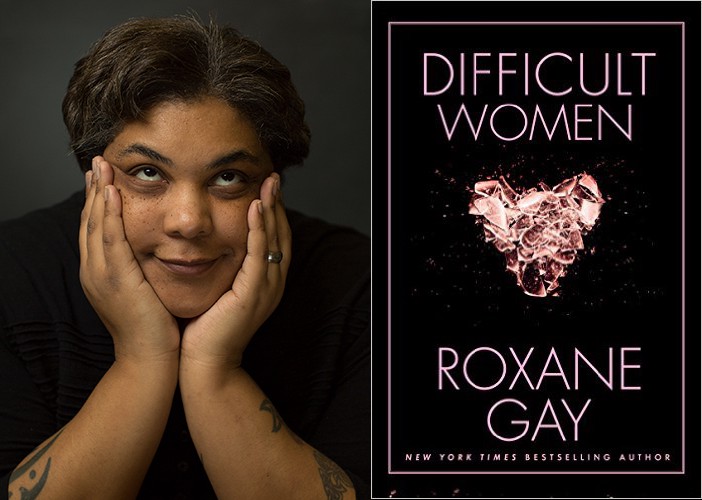

Roxane Gay Is Feeling Ambitious

The author of the new collection, Difficult Women, talks about putting in the work and following her “very dark imagination.”

Few contemporary writers are called upon to render opinions more often than author Roxane Gay, a consequence of amassing a readership through, among other ways, critiquing the culture at large with generous, entertaining essays, independent of the topic. To Gay, the Fast and the Furious movie franchise is as worthy of intellectual consideration as any obscure tome exhumed to brace esoteric points. Gay is always relevant and often correct, which not only explains, to some small degree, her popularity among fans across genres and aesthetics — from her new Marvel comic to co-writing a film adaptation of her debut novel — but also makes her opinion a highly-desired commodity, even if the matter at hand is of little significance or relevance to Gay. This leads to miscommunication, for lack of a better word, played out within Gay’s Twitter timeline, where fans and trolls alike commune for kind words or invective or impromptu requests for some kind of labor — intellectual, literary, even emotional — offering to young writers a glimpse of what literary stardom looks like, the necessity to remain, with restrictions, accessible to fans while protecting one’s private life.

Following the critical and commercial successes of her debut novel, An Untamed State, and her essay collection Bad Feminist, both published in 2014, Gay returns with Difficult Women, from Grove Press, a collection of short fiction that solidifies Gay as a writer just as committed to technique as she is to storytelling itself. The book includes the seminal stories “North Country,” “I Am A Knife,” and “Break All The Way Down.” Each word and every sentence in Difficult Women invites instead of repels the reader. Her erudition and ardor always strive for connection, and her blunt stories are anchored by curiosity and emotional depth while avoiding the maudlin, or needlessly grotesque plots. I spoke with Gay via email about Difficult Women, the short story form, her writing life, and the challenges of completing her new memoir, Hunger, due later in 2017.

Mensah Demary: “I Will Follow You,” originally published by West Branch, and again in Best American Mystery Stories, begins Difficult Women, a collection of realist yet vibrant stories of women and their lives, seen from their perspectives, told in their voices. It’s a disquieting story about two sisters and the trauma they both shared and endured. Why are they difficult women who, as written in the epigraph, “should be celebrated for their very nature”?

Roxane Gay: I don’t know that they are explicitly difficult women. The collection gets its title from one of the stories and certainly, many of the women in the book are difficult in one way or another, but not all. The protagonists in “I Will Follow You,” are, more aptly, women who have faced difficulties.

Demary: Many of these stories were published prior to your debut novel An Untamed State, soon to be adapted into a film, and Bad Feminist, the New York Times bestselling collection of essays. The stories are fresh and relevant to readers, and you’ve written quite a bit since they first appeared. Do the stories still feel fresh and relevant to you, the writer? Should such a question be of any concern to a writer?

Gay: I’ve long thought that most writers write the same story over and over, and certainly, in my fiction, there are some prevalent themes. When I re-read the stories in Difficult Women, there is a sense of being at home. I know these women and I know their hearts and in that, they are always going to feel fresh and relevant to me and hopefully my readers. The question I concern myself with is not if a story is relevant, but rather, if a story is both timely and timeless but that concern comes when I am revising. When I sit down to write, I just sit down to write what’s burning in my fingers.

Demary: Bad Feminist introduced your nonfiction to thousands, but many readers will be introduced to your short fiction for the first time with Difficult Women. Often, readers presume fiction to be a set piece for actual memories, or lived experiences. To what extent does this presumption prevent the reader from experiencing a short story as art, that is, as valuable independent of the story’s materiality relative to reality? Have readers forgotten how to enjoy a short story for its own merits, its imagination?

Gay: I’m not sure I understand the question. Readers often assume fiction is thinly veiled autobiography. They assume there is no art or craft to fiction. Those presumptions make for an impoverished reading experience. I cannot imagine thinking so little of a writer’s capacity for imagination. Alas. Some readers have forgotten how to enjoy a short story without obsessing over a story’s “truth” but not all and it’s our job as fiction reminders to continue to remind readers that fiction is fiction is fiction. The story is not about the writer at all.

Demary: Difficult Women’s titular story succeeds as it plays with roles assigned to women: “Loose Women” and “Crazy Women” act as sub-classifications further explored via vignettes entitled “What a Crazy Woman Eats” or “How She Got That Way.” The story is disinterested in edifying those who perpetuate these roles, caring more for reclamation and redefinition of language as it relates to women. The titles of your books make the same in-roads to this reclamation. Can a difficult woman be a bad feminist; do the ideas intersect in your mind? How should fans of your previous books approach Difficult Women?

Gay: Certainly, I am challenging the traditional idea of a “difficult woman,” much in the same way I challenge traditional notions of feminism with the phrase “bad feminist.” There are all kinds of intersections at play here. I don’t have any prescriptions for how fans of my other work should approach Difficult Women other than to read the stories with an open mind and an open heart and to recognize that as a writer, I contain multitudes and a very dark imagination.

I contain multitudes and a very dark imagination.

Demary: “Bad Priest” is a memorable story, and one of the earliest collected in Difficult Women, dating back to 2009, now a suddenly distant era. Father Mickey, a Catholic priest, and Rebekah, “a perfume girl in a department store who still lived with her parents,” have an affair: “The first time they fucked, they were in the church, and it was late — two in the morning.” Rebekah falls in love with Mickey but Mickey is preoccupied with himself, that is, with his soul in the eyes of mother and god. Mickey uses Rebekah to offload his shame. At what point does Rebekah get to deal and be present within her own life, absent the burdens of others, men, such as Mickey? When does a difficult woman get to drop her guard?

Gay: Why do you assume Rebekah isn’t dealing with her own life? In love, people often tolerate all kinds of bullshit. In “Bad Priest,” Rebekah is willing to tolerate Mickey’s self-absorption because she loves him and because, perhaps, she enjoys the taboo of having an affair with a priest. Rebekah isn’t passive in their relationship, nor is she naïve. I think Rebekah and Mickey see each other exactly as they are. Sometimes, that’s a relief.

I don’t know that a difficult woman ever drops her guard. She knows better.

Demary: Do you still write short stories? Are there collections you’ve recently enjoyed, or those that remain memorable to you?

Gay: I still write short stories. I will always write short stories. I’ve got a few I’m working on right now but sadly, I always have to put them at the back of the queue of what I’m working on. No one is ever clamoring for short stories from relatively unknown writers but that’s okay. I write them anyway. I recently enjoyed Always Happy Hour by Mary Miller and Homesick for Another World by Ottessa Moshfegh — both dark, strange, a bit uncomfortable, sexy. One of the most memorable collections remains How to Suffocate Your Own Fool Self by Danielle Evans. Each story in that book is exquisitely crafted. Whew. That woman can write.

Demary: Your Marvel comic, Black Panther: World of Wakanda, published its first issue in November, 2016. What has been the response, the feedback, from your readership, now larger and all the more diverse as many comic book fans read your words for the first time? What is it like to write a world populated and influenced predominately, if not entirely, by black women?

Gay: The response, so far, has been overwhelmingly good. I was really nervous about World of Wakanda because I am new to comics and I was writing into a really established canon but readers have been very generous. It’s exhilarating to write a world dominated by black women. We need more work like this, work where whiteness isn’t the default, and where it isn’t even something of relevance to the stories we tell.

Demary: In GQ, a article in conversation with John Malkovich advised against ambition as a motivating factor in every day life, and in art, dismissing it simply as “the need to prove something to others” and “a need for rewards outside of the work.” You’ve written about ambition before, and it appears as a theme more than once in Difficult Women. Can ambition distract at times from the work, in this case, the writing? How much does ambition motivate you toward new challenges, writing a comic book for the first time, for example?

Gay: Eh, people have strange ideas about ambition as a dangerous thing because they only want certain kinds of people (ahem) to be ambitious. I vigorously encourage women and people of color to be ambitious, to want and work for every damn thing they can dream of. We’re allowed to want, nakedly, as long as we’re willing to put in the proverbial work. Ambition is a distraction if it’s the only motivator. I am ambitious because I love what I do, not simply for ambition’s sake. Ambition is what allows me to take creative risks and try things I never thought I could do. Ambition makes me a better thinker and writer. Ambition makes me.

Ambition makes me a better thinker and writer. Ambition makes me.

Demary: Do you maintain a writing routine, a regiment perhaps forced due to workload, and if so do you work in time to write for yourself, to write something other than work assigned or commissioned by third parties? How often do you read for pleasure these days?

Gay: I have no real routine or regimen. Because of a very hectic schedule, I write when I can, where I can, as often as I can. I am writing this at 2 am at my parents’ house. My brother is snoring loudly two rooms away and I can hear him. Before I started tackling these questions, I finished the first draft of the screenplay for An Untamed State which I mostly wrote on a couch in Los Angeles and finished up here. Tomorrow, I’ll finish revising Hunger and work on my anthology Not That Bad which I hope to assemble and turn in by 1/3. I don’t really write for myself as much as I want but when I do, I write fiction. I try to make the time at least once a month. I read for pleasure quite a lot, pretty much on a daily basis, before bed, in the morning. I read a lot on airplanes.

Demary: Your first memoir, Hunger, also to be published in 2017, is highly anticipated; you revealed via Twitter some struggles in completing the book, and I imagine there is some trepidation in being so revealing of yourself for art’s sake, which makes me think you decided to write Hunger for reasons beyond yourself, for a goal other than personal catharsis. Should that be the goal of all memoirs, the reach toward the outside, toward other people, in spite of the form’s inherent insularity?

Gay: The vulnerability demanded by Hunger terrifies me so I have dragged my heels quite a lot. It will have delayed the book a year when all is said and done. I am, in fact, a very private person but I think it is absolutely necessary for more people to write about different kinds of bodies, the truth of living in those bodies, without necessarily framing those stories in narratives of triumph and conquer. So, yes, I am absolutely writing this book not just for myself, but for anyone, and especially any woman, who has struggled with trauma, being overweight, the cultural expectations we place on bodies, and the perpetual diet so many of us are on. Personal catharsis has nearly nothing to do with it. This is my first memoir so I would not presume to declare what the form should do but I believe all great writing looks both inward and outward.