Books & Culture

My Nostalgia for Enid Blyton is Complicated

Reckoning with the racism of my favorite childhood author

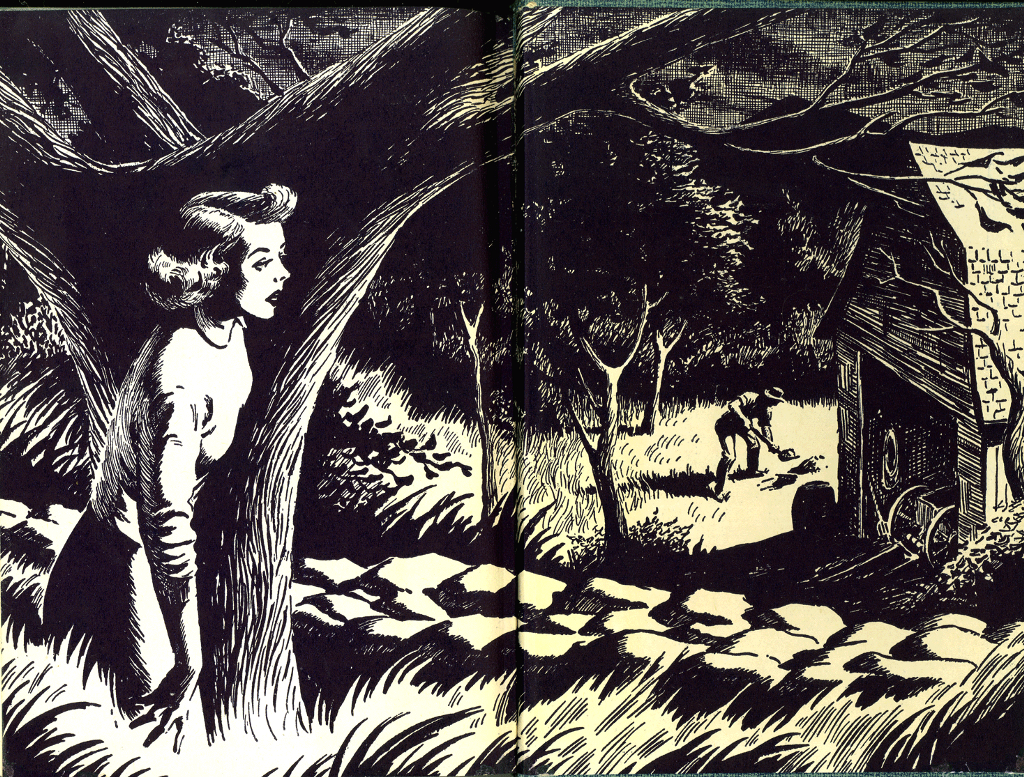

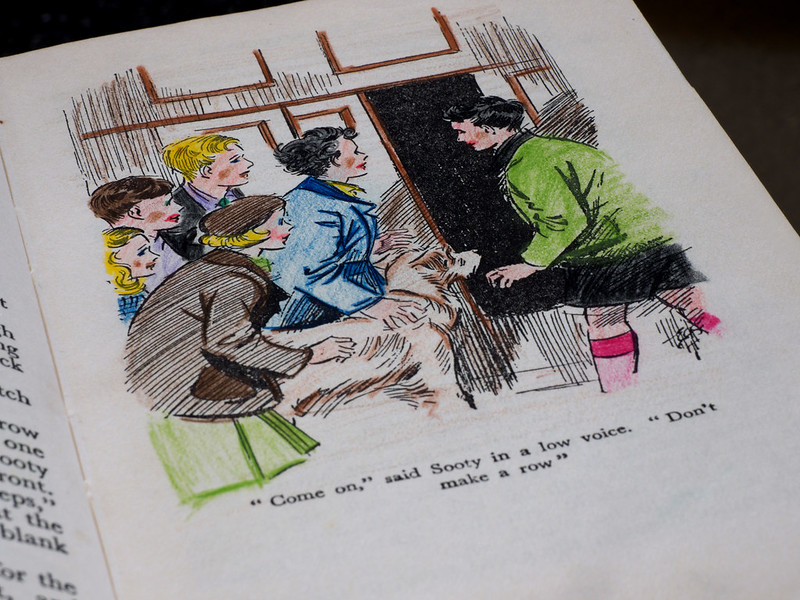

I can’t quite recall how old I was when I read my first book by Enid Blyton, though I remember the book itself: Five On A Treasure Island, the first in her Famous Five series of mystery novels which feature an eponymous group of four adventure-prone children and their beloved dog. Perhaps the best-known of her many series, The Famous Five was my introduction to the works of the British children’s author, who in 2008 was voted Britain’s best-loved writer—surpassing literary giants such as William Shakespeare, Jane Austen, and Charles Dickens. When I started reading it, I was instantly hooked, and like millions of others who had found themselves captivated by her gripping plots and beloved characters, Blyton quickly became my favorite author. From that day forward, I was rarely seen without a copy of one of her books—I carried them everywhere with me, stuffing them into my backpack before school and stowing them in the back seat pockets of my parents’ cars so that I would never find myself without a Blyton close at hand.

Like many writers, I was a reader from the moment my arms were strong enough to hold up a book on their own, and Enid Blyton’s stories marked some of my earliest forays into the world of chapter books. The charm that Blyton’s books held for my childhood self lay, in large part, in the fact that they spanned across a wide range of genres—her mysteries and adventures occupied a permanent place on my shelf right next to her school stories, with a healthy dose of fantasies and fairy tales sprinkled into the mix as well. As a child, I had always used books as a way of escaping into different worlds, and her books provided me with no dearth of worlds to choose from. Beyond their seemingly endless variety, however, her stories also tended to feature characters who were around my age. This meant that as I read, I was able to picture myself taking part in the action alongside her juvenile protagonists, sneaking out of boarding-school dorm rooms for illicit midnight feasts or rowing boats out to sea to investigate gangs of smugglers hiding in ruined island castles.

Less attention has been paid to the more insidious facet of her popularity—the enduring legacy, more than half a century on, of British colonialism.

In many ways, my childhood love for Blyton’s stories can be traced back to the fact that even her most thrilling adventures started out in unremarkable English villages that just as easily could have been my own home town, their quaint stone houses and neatly-arranged gardens closely mirroring the manicured lawns and cookie-cutter McMansions of the sleepy suburb where I grew up. These idyllic small towns were inhabited by ordinary children whose lives were no more inherently exciting than my own—save, of course, for the hair-raising adventures that they somehow managed to stumble upon whenever they came home from school on holiday. If these children could go on adventures despite their painfully ordinary lives, I figured, then there was no reason why I couldn’t do the same, and my fanciful mind quickly began to conjure up secret passageways hidden in our coat closets and fairy houses tucked away under the rose bushes in our garden. Blyton’s stories fed my overactive imagination and taught me to view the world around me with a wide-eyed sense of adventure, lending a fantastical air to an otherwise mundane suburban upbringing.

Born in South London in 1897, Enid Blyton published her first book, a collection of poems entitled Child Whispers, in 1922. Over a period of nearly five decades, Blyton published more than 600 books and quickly established herself as a giant of British children’s literature through beloved series such as Noddy, The Famous Five, The Secret Seven, and Malory Towers. To this day, she remains among the most beloved children’s authors in British history, her books having sold more than 600 million copies. In the decades since Blyton’s death in 1968, however her work has increasingly come under fire for what many perceive to be racist, sexist, and otherwise offensive attitudes, ranging from antiquated gender roles and crudely-stereotyped nonwhite characters to the casual use of explicit racial slurs—the original edition of one Famous Five story describes the character George, after climbing down a train shaft, as being “black as a n****r with soot.”

While these criticisms became much more widespread in the 1980s and 1990s, prompting publishers to begin revising subsequent editions of her books in order to remove outdated and offensive language, Blyton’s reactionary views were not immune to condemnation during her lifetime. One 1966 column in The Guardian, written by Labor Party MP Lena Jager, sharply criticized racist themes in Blyton’s story “The Little Black Doll,” in which a doll named Sambo is accepted by his owner and the other toys only after his “ugly black face” is washed off by a shower of “magic rain.” Even her own publisher Macmillan, in an internal review of her manuscript The Mystery That Never Was (which they subsequently rejected), criticized the book for “a faint but unattractive touch of old-fashioned xenophobia in the author’s attitude to the thieves,” whose “foreign” nature “seems to be regarded as sufficient to explain their criminality.”

The controversies surrounding Blyton’s work have gained renewed attention in recent years, as the United Kingdom—like the United States—has started to undergo its own long-overdue racial reckoning. In 2019, the Royal Mint scrapped plans to issue a commemorative coin honoring Blyton, fearing potential backlash over the author’s “racist, sexist and homophobic” views, and last year, English Heritage—a charity which manages over 400 historic sites across England and administers London’s famous blue plaques, which mark places that have links to significant historical figures— acknowledged Blyton’s racism for the first time, updating its website to note the criticisms that her writing received both “during her lifetime and after” for its “racism, xenophobia and lack of literary merit.” This recent spotlight on Blyton’s personal bigotry, which she did little to prevent from seeping into her stories, has sparked a debate in British literary circles over the appropriateness of her enduring popularity. Less attention, however, has been paid to another, arguably more insidious facet of her popularity—the enduring legacy, more than half a century on, of British colonialism.

Although her stories occupied an outsized place in my early childhood, not one of my American peers growing up had any idea who Enid Blyton was—nor did they care. When, in elementary school, I purchased a boxed set of the Malory Towers series during a family trip to India and proudly donated it to my school’s library—an act of literary philanthropy that, in my mind, made me the second coming of Andrew Carnegie himself—I was disappointed to watch the books remain untouched on the shelf, gathering a thin layer of dust as my classmates ignored them in favor of other, more familiar fare. I quickly realized that, as the sole Indian student in my class, the only reason I knew about Enid Blyton at all was because I had been introduced to her by my parents, who had themselves been raised on her stories while growing up in India.

I was aware from an early age that colonialism was a violent and exploitative institution which had robbed my mother country of incalculable wealth and innumerable lives.

To this day, Blyton remains immensely popular among Indians who, like my parents, grew up reading her. She consistently ranks among the top-selling children’s authors in India, and the managing director of Hachette India, which distributes her books in the subcontinent, told the BBC that “Blyton is one of the few author brands whose work remains unshakable.” Despite rarely, if ever, appearing on bookstore shelves in my hometown, Blyton’s books were always widely available in India, and whenever we visited our family in Bombay I would stuff my already-overflowing suitcase with copies of her books that I bought by the armful from the Crossword bookstore in Kemps Corner. During these outings, I never once stopped to ask how her books had gotten there in the first place.

As a child, I never gave much thought to the subtle vestiges of British influence that occasionally asserted themselves in conversations with my parents, popping up every now and again in the inflections of their accents or the way they spelled certain words. I knew that nearly every aspect of the world they had grown up in, from the trains they rode to the schools they attended, reflected similar influences in one way or another, the result of two centuries of British rule over India. The fact that they, like millions of their peers, had grown up reading British authors like Enid Blyton seemed to me to simply be yet another example of this influence, and I therefore paid it little mind. Though I was aware from an early age that colonialism was a violent and exploitative institution which had robbed my mother country of incalculable wealth and innumerable lives, my juvenile understanding of colonial violence had not yet extended to encompass its less overt manifestations—the subtle mechanisms of cultural hegemony, such as the enduring adoration of a white author by millions of brown children, that enable and reinforce the violence of a colonial regime.

Blyton’s stories presented me with a world in which I had to subconsciously whiten myself in order to fit in.

Commenting on Blyton’s lasting popularity in India, Indian journalist Sandip Roy wrote in the Times of India that “she colonised us with crumpets and make-believe.” (Note, in Roy’s description, the British spelling of “colonized”—an irony so delicious that it could merit its own essay.) Captivated as I was by Blyton’s stories, my childhood self was not immune to this literary colonization, and I eagerly devoured her sanitized descriptions of British childhood. In a haze of Anglophilia that must have caused my freedom-fighting ancestors to spin in their graves, I wished for nothing more than to have been born British, to occupy the ginger-beer-soaked world of midnight feasts and countryside picnics that filled the pages of Enid Blyton’s books.

Blyton’s was a world of prim boarding schools and sleepy English villages, where lily-white children with monosyllabic names ate meat pies and tinned sardines rather than the heavy, spice-laden Indian meals that filled my family’s dinner table each night. Even as I imagined myself growing up alongside her protagonists, it never occurred to me that I, with my brown skin and Indian name, would in all likelihood have been shunned as an unwanted intruder, or at the very least regarded with haughty suspicion for my supposed foreignness. Adding to this postcolonial irony was the fact that the England I longed to inhabit, represented so idyllically in Blyton’s books—most of which had been written nearly a full half century before I was born—no longer existed, making my misplaced nostalgia for the Britain of the 1950s not unlike that of the flag-waving, jackbooted ultranationalists who, to this day, fight tooth and nail to keep people who look like me out of “their” country. Rather than giving me a world in which I could truly see myself, then, Blyton’s stories presented me with a world in which I had to subconsciously whiten myself in order to fit in.

As a child, however, I remained blissfully (and perhaps willfully) oblivious to these uncomfortable realities. Instead, I immersed myself uncritically in Blyton’s works, allowing my love of her writing to lay the foundations for a misguided Anglophilia that lasted into the early years of high school, spurred along by an adolescent pretentiousness that equated all things British with elegance and sophistication. Enid Blyton was just the gateway drug—the floodgates having opened, I began to eagerly seek out any and all of Britain’s many cultural exports. Sherlock Holmes, Downton Abbey, Jane Austen’s novels—if it was stamped with a Union Jack, I couldn’t get enough of it.

I still can’t seem to shake the warm, nostalgic comfort that I feel when I think about those stories.

Throughout all of this, I never sought to deny the painful history of British colonialism—instead, I simply chose to look the other way, putting it out of my mind in favor of more comfortable, depoliticized aesthetics. It wasn’t until I got older, and my nascent left-wing sensibilities had finally begun to develop from an ill-defined patchwork of amorphous principles into a more coherent, systemic political ethos which held anti-imperialism as one of its central tenets, that I began to confront these questions for the first time. What did it mean that as a child, having never learned my mother tongue or expressed much interest in connecting with my roots on any meaningful level, I felt more connected to the art and literature of my people’s colonizers than that of my own culture? What did it mean that this author, so beloved not only to me but to my parents, and to millions of their fellow countrymen and women, was a household name in India solely because of colonization’s far-reaching legacies? And what does it mean, even knowing all that I know now, that I still can’t seem to shake the warm, nostalgic comfort that I feel when I think about those stories?

My feelings towards the nostalgia that Enid Blyton continues to inspire in me are, predictably, complicated—colonial legacies notwithstanding, it is highly unlikely that without her stories I would have ever developed the all-consuming love of reading and writing that has since come to define me. These complicated feelings appear in some ways to resemble those that many people who grew up reading the Harry Potter series, to which many similarly attribute the genesis of their own literary passions, have had to grapple with in recent years, as J.K. Rowling’s transphobic bigotry has become increasingly difficult to ignore. Rowling is arguably the first and only British children’s author to approach the levels of adulation and name recognition that Blyton has long enjoyed, and like Blyton, she too has come under fire in recent years for her trans-exclusionary views, forcing millions of people who grew up on her books to suddenly reckon with this newly-unearthed dark side to their childhoods.

To simply abandon nostalgia altogether in the name of dearly-held principles is far easier said than done.

The controversies surrounding Enid Blyton and J.K. Rowling, though different in many ways, both raise important questions about the limitations and pitfalls of childhood nostalgia. For most of us, immersing ourselves in nostalgic reminiscence is the only way we know how to revisit and relive the joyful simplicity of childhood, when everything made sense (and that which didn’t, we simply chose not to bother ourselves with). In the process, we tend to romanticize those touchstones of our younger days—the books we read, the movies we watched, the songs we listened to—that stick out most prominently in our memory, even years later, and we project onto them an additional (and perhaps undue) degree of symbolic significance. But what happens when these touchstones, and the people that created them, cannot easily be separated from movements, ideologies, and institutions that are diametrically opposed to everything we stand for? What happens when they cannot be separated from social ills that affect not only us, but the people we love? To simply abandon nostalgia altogether in the name of dearly-held principles is far easier said than done, and doing so does not erase the fact that, regardless of our values or principles, these touchstones played an integral role in shaping us into the people we are today.

Unfortunately, I don’t have the answer to any of these questions—I don’t think anyone does, which is precisely what makes these questions burn so intensely in the first place. The fraught touchstones of our childhoods are just one small facet of a much larger reality—the reality that we have all been shaped by a world over which we never had any real control, by people and places and cultural artifacts that may have dark sides as well as nurturing ones. Perhaps there is some comfort to be found in the apparent universality of this experience. Whether our cherished childhood memories involve reading The Famous Five or Harry Potter under the covers with a flashlight, watching The Cosby Show with our families on Thursday evenings, or listening to Michael Jackson and Eric Clapton on our parents’ car stereos, few of us have managed to come of age without having to confront, at one point or another, the painful realization that some aspect of our childhoods was not as innocent as we once believed it to be. Maybe that’s what growing up is all about.