interviews

Imagining Life as an Inanimate Object

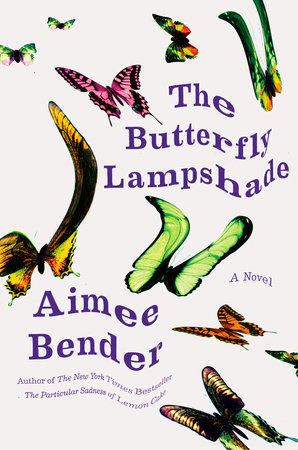

Aimee Bender’s "The Butterfly Lampshade" is a fabulist novel about mental illness

In Aimee Bender’s new novel, The Butterfly Lampshade, Francie reflects on a journey from Portland to Los Angeles she took as a child after her mother smashed her own hand with a hammer and was institutionalized. Francie is haunted by childhood images of a butterfly painted on a lampshade coming to life only to drown in a glass of water (which she then drinks) as well as other drawings, like a beetle and a rose on a curtain’s design, transforming from likeness to corporeal form. These memories confront Francie with uncomfortable questions: Were they real or in her imagination? Is she losing her mind the way her mother was? She constructs a “memory tent” with her cousin Vicky, where she can finally face them. While dealing with her surreal recollections, violent thoughts intrude on Francie’s mind, keeping her locked in her room from the outside so she can’t, as she believes she will, hurt anybody.

Like Bender’s previous novel The Particular Sadness of Lemon Cake, The Butterfly Lampshade delicately uses fabulism to illustrate mental illness in her protagonists. Reading it, I felt a deep kinship to the book’s emotional landscape and the way it so perfectly illustrated the pain of the intrusive thoughts that plague me every day. Bender’s methodical descriptions of the images make them erupt, so that the story is not so much about moving the story forward, but closely examining the precarity and psychological impact of each passing moment. As the book unfolds, these moments are revisited and expanded so that they take on new, sometimes uncanny meanings. The Butterfly Lampshade delves into the elusiveness of memory, the paralyzing nature of anxiety, and the importance of the journey towards healing.

I spoke to Aimee Bender about intrusive thoughts, the uncanny valley, and the rupture between mind and reality.

Melissa Lozada-Oliva: Do you experience intrusive thoughts? I was diagnosed with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder a year ago and I sometimes think thoughts like, “Someone is trying to poison me” or “I am going to cut off everyone’s head,” stuff like that. Your character Francie imagines violently stabbing her cousin’s soft infant head so intensely that she needs to lock herself in her room. Could you speak more on how intrusive thoughts have shaped your writing and your characters?

Aimee Bender: Yeah! I have OCD too and it has had this really, really painful side. Something that was helpful to me once was this Edgar Allen Poe essay called “The Imp of the Perverse” which is about that impulse to do something destructive and how common it is! In the essay, Poe talks about these impulses as a little imp telling you to do something you don’t want to do.

One of my clearest memories of this is when I was 21 and my boyfriend got me a trip on a hot air balloon with him in San Diego. The whole time I was thinking “Why am I not jumping out of this balloon? Like, what is keeping me inside this balloon?” There was no barrier. I was anxious the whole time, I could barely enjoy it.

I’m 51 now and after much therapy and life experience, the separation of thought and action feels super interesting to me. What felt so important to me about the book was to think through different minds navigating this blurry line between thought and action. For a character who is psychotic, their sense of reality becomes unclear. Events may be clear to someone outside their world, but someone going through a psychotic episode might not know where the boundaries are. Everything is super porous. And for a person with OCD, you think what is porous is not. You think if you have a thought it will translate into an action. But I think the vast majority of us are just scared of our thoughts!

One of the simplest things in my own therapy was just thinking, “Have I ever done any of these things?” Well no, I’ve never done any of these things, but I’ve thought a million things. You know, even just holding my baby and thinking “I wanna throw the baby against the wall.” Terrifying. But also, I was never going to throw the baby! I took such good care of my babies. I’m at a point where I realize my thoughts are just thoughts, I’m not scared of them anymore. But I wanted Francie to be not at that point yet.

MLO: Francie compares the Ovid myth of bringing a statue to life to an active shooter at a movie theatre, a situation much like the Colorado Dark Knight shooting in 2012. That’s actually an intrusive thought I have! Francie describes how the shooter, dressed up as a character in the movie, was stuck in this transference between thought and reality, kind of being stuck in like the uncanny valley.

AB: Part of my interest in this book was trying to track two different realms. Francie does this literally with a train ride between a world where reality is less fixed and a world that is clearer. Her cousin Vicky belongs solidly in the clearer world, but Francie’s mother, Elaine, exists between these two worlds.

So, yeah, you’re right, it is the uncanny valley and it is the Colorado Batman shooting. When I heard that story it was a scary example of someone traversing a line that we can usually trust. Of course, the vast majority of people who suffer from psychosis are not acting on their thoughts, they’re just wrestling with them. There was a rupture for the shooter, first in his mind but later a rupture that became real for both him and the audience. The rupture must have been so clear inside his mind. That made me trip out and wonder if all violence is the projection of someone’s mind onto someone else’s body. And like, probably! How we treat each other gets all muddled up in that.

As for Ovid, I’ve always been attracted to that story and to stories of the inanimate becoming animate. We’re so willing to make that move, to accept that. And yet, it’s so scary if people really believe it to be real, when the boundary is crossed. A statue that comes to life is beautiful in theory, and most of us know that it’s the realm of the imagination. But for someone else it’s not, and that can be really scary.

MLO: Yeah, it’s frightening! You revisit that rupture when Francie’s mother gets upset at her for destroying all of her stuffed animals, because her mother believes them to be real. I used to have a stuffed animal named Princess. If she fell on the floor, I would kiss her and apologize until eventually I learned that there was no little brain inside of Princess.

AB: But it takes so long to learn that, right? I slept with so many stuffed animals and I felt so bad deciding who I should kick out of bed. Then that feeling became so oppressive! It started out so empathic and then it became a horrible thing where I couldn’t move while I was sleeping.

I’ve always been interested in the point where the beautiful tips into the grotesque and the grotesque tips into the beautiful.

I’ve always been so interested in the point where the beautiful tips into the grotesque and the grotesque tips into the beautiful. When we look at things closely, how do they shift? Take the intrusive thought: it feels very scary, but it’s ultimately not that scary when you realize you’re not going to act on it. Then you can be like, “Okay, I have such an imaginative mind, I just want to hop around into every thought!” And it’s all in there. It’s part of what makes me want to sit down and write. All these things that feel awful and beautiful.

MLO: This year I’ve had this really sick feeling that I can predict the future? But just because something turns out to be true doesn’t mean I’m in touch with something greater. But then also I’m like, well what if I am?… I don’t know.

AB: No, I understand! I’ve had that thought too! You can run the numbers and make enough predictions and you might hit one but that doesn’t mean that you’re psychic! [laughter] It just becomes a way to turn on the self. It becomes a way to scare yourself and I think Francie scares herself so much she has to lock herself in a room. I certainly have felt frightened of my own thinking to the point that I would limit my thoughts.

MLO: Now I’m kind of thinking of this book as a horror story.

AB: It is in a lot of ways!

MLO: One of the scariest moments in the book is when Francie and the steward who is chaperoning her run into these strange people on the train, who seem not of this world. They sound like they’re trying on the English language and there is no record of them being on the train. Were they from another kind of place? And is that the place that Francie and her mother belong?

AB: The meaning is sometimes elusive to me, too, but I do think of them as living in a kind of the realm of the butterfly and the beetle and the rose. The people on the train exist in that place and they’re comforting to Francie because she is in a moment of transition and the people are somehow part of that transition. I wanted the steward to be able to see them because I didn’t want them to be a figment of her imagination.

This goes back to the uncanny valley. Francie is so unmoored at that moment in her life. There’s a portal opening for her to somewhere else, but something in her life stabilizes, the portal closes, and she can finally start to set some roots. I don’t think the people on the train are malevolent. I just think they come from somewhere else. They offer something else to her, they ask her for some tickets and all she has are these items, the butterfly and the beetle and the rose. She could go with them but she doesn’t.

MLO: I read The Butterfly Lampshade along with my friend in Arizona and they actually had a question for you. They compare Francie’s mother Elaine living in the institution to a princess trapped in a castle. The institution even has an “aura of a decaying European castle.” Is the institution in the book based on a real institution, where patients would live in the extra space of a nursing home? What do you want to say about the reality of institutions or is it only a metaphor?

AB: I had an aunt who was in different institutions for most of her adult life. We would visit her once a month. She was probably in her 30s, and she was often in places with elderly people. She had a severe bipolar diagnosis with psychotic episodes and she was intellectually disabled. She had multiple accounts of struggle. And she moved a lot in the 1970s and 80s, so we would see that, you know, this institution is more hospital-like, this one is actually a nursing home, this one is a house. That was in mind when writing Elaine’s place, but the room she stays in isn’t actually a room that I associate with my aunt. I like the princess in the castle idea, but it was important for the room to be beautiful and decaying, to have a transitory quality, for all that beautiful stuff to be delicate and crumbly. That’s a metaphorical piece. But the cafeteria and the gathering in the institution, all of those details come from experience.

MLO: Do you think we’re in the uncanny valley right now? Like we’re on a long train ride to our new future and waiting to be let off, like Francie?

AB: The only real thing I can say about it in relation to the book is that I feel so clearly like I cannot process it. I am just moving through it and trying to make it work. I’m barely able to take in the numbers of COVID deaths, barely able to take in the fear. As a friend of mine was saying, walking down the street you feel like you’re both predator and prey. If the neighbor’s kids come too close, you move back. Things feel painful and there’s no space to process it. I think it will take time. I’m certainly not able to be like, “Oh, this is what this was like,” I’m more like, “Ahh!!”

MLO: Ahhh!

AB: There’s something related to intrusive thoughts that I found so moving that I’d just like to talk about, which is this memoir by a lawyer named Elyn Saks called The Center Cannot Hold. She was diagnosed with schizophrenia and what helped her most has been the medication. Now she’s medicated, she’s able to practice law, she’s married, she’s been able to create a life for herself. But she still started psychoanalysis because she had anxieties. In The Center Cannot Hold, she talks about going in and laying on the couch and saying, “Today, I murdered 40 people.” And she didn’t, but she felt like she really did! It took courage for her and her analyst to sit with the darkness of that thought and the confusion. I found that so beautiful. And that she was willing to write about the strangeness of our minds so openly. She knows better than anyone what it’s like to traverse between realms.

MLO: In both this novel and The Particular Sadness of Lemon Cake the main characters don’t get to have a love story. There is beautiful familial love with Vicky for Francie, but both Francie and Rose from Lemon Cake have to deal with whatever is going on in their heads alone. What was the choice there?

AB: There are people that can work out some of that stuff with a romantic partner, and can be part of the process, but there’s a time before you can even make that step with someone else. So Vicky, Francie’s cousin, plays a crucial role in Francie’s growth by saying, “I don’t think you’re going to kill me! I want you to leave the door open!” But there is a very small detail at the end where she’s looking at the two chairs on her balcony. I wanted to evoke a feeling that there was space made for someone to come into her life where there wasn’t before. If you’re locked in your room like that, you can’t really have someone over because you think you’re gonna kill them! Something has to be opened up a little bit to make that space for that second chair. It’s such a small detail but it’s an important shift. The direction of the ship for Francie had shifted enough. Same with Rose from Lemon Cake, some people are sad she’s not with George. And I love the character of George as a partner for Rose, but there’s absolutely no way that Rose was ready for that! George is leaps and bounds ahead of her relationally. He would be an old man by the time she was ready. But Rose and Francie are both on the right path. I want to see the character in a direction towards personal connection, to feel a sense of possibility for Francie without making it concrete.

MLO: That’s really beautiful. They’re waiting for the right train while other people already got to where they needed to be.