Books & Culture

The Vernacular Music of Aziza Barnes’ i be but i ain’t

Barnes’ collection is an innovative, hybridized work that should not be grouped into a single aesthetic

On a recent episode of The Poetry Gods, a podcast Aziza Barnes hosts with Jon Sands and José Olivarez, the hosts were asked for their ideas around gatekeeping. They addressed the question in the context of white academic institutions and within more diverse art venues as well. Barnes said that rather than fling open the gates, she supports gatekeeping maneuvers that “aren’t insidious but are necessary,” preferring “a slow welcoming in.” She likened this sort of necessary gatekeeping to a favorite Auntie who invites you into her house “but she’s like, ‘Don’t put your shoes on my table.’”

It is, perhaps, the invitation potential readers of i be, but I ain’t (YesYes Books, 2016) needed. Barnes’ first full-length book is racially charged. It is also an example of innovative, hybridized work that should not be grouped into a single aesthetic. With it, Barnes has advanced the need for thinner taxonomies for both Black poet and poet.

But for now, a question — one asked in two separate poems from i be, but i ain’t titled my dad asks, “how come black folk can’t just write about flowers?” The extended answer circulates through this book’s pages. In one my dad asks poems, the speaker is a girl from nowhere but with an ID (with a “government name”) and house (“held by legislation vocabulary & trill”) in a neighborhood where crime watchers surveil their own residents. Here are some early lines:

[…]it’s ours & it sparkle on the corner of view park, a channel of blk electric. danny

wants to walk to the ledge up the block, & we an open river of flex: we know what time it is. on the ledge, folk give up

neck & dismantle gray navigation for some slice of body. it’s june. it’s what we do.

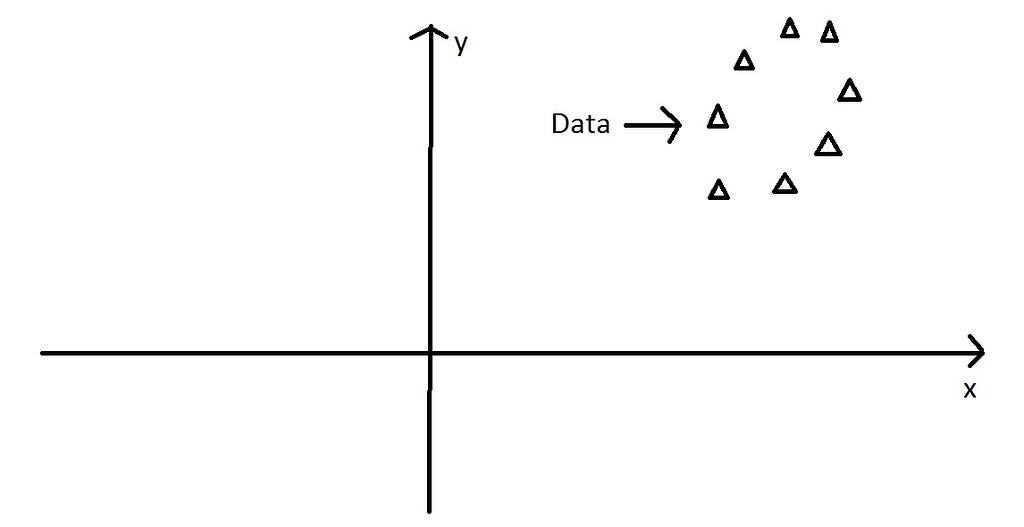

It’s thrilling how Barnes exploits the beauty and wit of the vernacular and teases the gap between dialectal and non-dialectal poetry. She draws attention to the fact that language is bound by meaning, accessible to those who share its understanding. In a broad sense, she signifies. When Henry Louis Gates, Jr. published The Signifying Monkey, a book of African-American literary criticism, in 1988, he posited the idea of the perpendicular intersection of language, where, simply put, the x axis represents the literal definition of a word as defined by the masses (let’s call it white) and the y represents the signifying or Black vernacular. The intersection, according to Gates’ theory, provides a rich poetic playground for writers, poets, hip-hop artists and Twitter users alike. For a poet like Barnes who works with multiple layers of diction and code shifting, the collision of subject matter, music, and meaning allows complex ideas to surface. Language like “flex,” “trill” and “give up neck” has a vernacular music, but her grammars don’t stop at jazzing in this june; they include margin and arterial, squad cars and a young Black man dead way too soon. “i swift,” says Barnes’ speaker, “review the architecture of desire spun clean, & I could see how we all look like ghosts.”

Stagy, humorous, vulnerable and awash in blood crimes, dialect hits its heights in i be, but i ain’t as Barnes plays in the space between Gates’ x and y axis. It’s interesting to contrast the above lines from my dad asks with lines (the poem’s first and only) from self-portrait as a lily white fist:, where the dialectal music breaks open and apart, and the Gates’ axis could be considered to fall away:

Humanness does allow for some prudent bleeding. I am ungloved in a sabbath of spit.

Only the turn of cement can arc Black. I am blue damage. Mother gut & tower.

Truth: we are all for rent. Red lined systems. The door out is green and full.

Indirection is one favored rhetorical technique that creates the bread and butter of Barnes’ verse where a word like “everyone” is instead “every fiber owning a name.” Her sentence construction is elegant and complex: “You run menace to my name is the beginning of a sentence that ends with a lie I make about love & how I am above it.” She puts out a cigarette “before its time” while “Nervous / White Lady smile under / / that hard side part it all // clicking // in my glass.” The ecstatic discursiveness in how to kill a house centipede by squishing it behind a photo of miriam makeba while contemplating various iterations of rigor mortis in my gentrified apartment complex on 750 macdonough street brooklyn, ny 11233, goes five levels deep (not unlike its title) and ends up at the sublime. If you aren’t enjoying this, your heart has stopped sending blood to your vitals.

Descendants is a series of four poems after an installation by performance artist Ramellzee. His stranger-than-science-fiction characters become successors of very terrestrial concerns in Barnes’ hands whose dictums include, “How my mother taught me not to get killed. Why not don’t kill me?” Here is part of the monologue of Alpha-Positive:

I stay nimble as parades of men

with forefathers try to examine my mouth

cupped up like a horse & stretched I flex.

I shine

& stay shinin’ til my maker

whose name I covet as my first come back

down & break it down: why he make of me

such garbage? Such inoperable shame?

Barnes’ wonderful Pulp Fiction series of poems is keen cultural criticism with the personal as stock scenery. They dialogue with others poems in which cinema provides a troubled backdrop, such as the mutt debates what it might come down to:, a poem I love for its emotional and linguistic hall of mirrors and its cathartic use of Pam Grier, both afro-clad character of Blaxploitation films and the “real” Grier, to play object for the brutal betrayals of the body, exacted internally and externally. The book’s’ “mutt” poems provide the steel frame of its construction: they are an exploration of identity and its clashes — against self, illness, and race and gender.

Add sexuality to the list, addressed most pointedly in the later sections of the book. Each of its five sections begins with a quote from Stonewall Jackson, and the fourth section’s epigraph is, “My religious belief teaches me to feel as safe in battle as in bed.” Barnes cunningly bends the meaning of bed to her own bidding, flipping the switch on this ambiguous figure in the history of race while keeping the war. These poems are explicit and vulnerable, both sexually and emotionally. Even as my allegiance tends toward poems that appear earlier in the book, these are gratifying in their composition from start to finish. pronunciation: part one is a network of linguistic redoubling in which the speaker is surrounded by shrines of Jesus that she is told are “mostly ironic” and declares that “consent is a mule we never got.” A little later, from alleyway:

[…]Sometimes I want to eat my breasts down to their bitter rind & spit them out. I want to be the bitter rind without suck and easily thrown. Easily thrown I want to be the pebble thumbed & wished upon before enveloping the lake I sink in. I sink in you the lake & by lake I mean gutter a water that does not hold me well. Here we are not the bodies our mothers made.[…]

Barnes has alluded to it in interviews, but I’ll say it here: She’s a Pepper LaBeija girl living in a Lena Dunham world.

If axis-plotting has fallen away in self-portrait, it is a distant memory in a good deed is done for no good reason, the book’s final poem. It is a meditation on the nature of humanness and a deep dive into extended metaphor. While it plays wonderfully on the stage, it is a poem that loves the page as well. Its ruptured-block form, simultaneously contained and expansive, is the visual element that stands in for sound. It is Barnes’ control and restraint that make it perhaps the most audacious poem in a book ablaze with audacity. In the poem, “you” is a personified slab of wood, where “you allow yourself to become whatever these hands will make you.” Decontextualized, it is a poem anyone can live in, but it is also a Black woman’s poem of self-definition and restoration, the plaint of mutt and bastard, the child of no one, who says, “you aren’t dire but you were the difference.”

Barnes, am MFA candidate at the University of Mississippi, is one of the founders, along with Nabila Lovelace, of The Conversation, an ambitious multi-media project that spotlights writers in the American South. The Conversation sponsors workshops and craft talks, hosts a fellowship program, and this October took the form of a week-long tour through three Southern states talking to writers who will further Barnes’ and Lovelace’s dedication to “bridging conversations between inter-regional Blackness & discussing what a Black Mecca can look like in the United States.” Henry Louis Gates, Jr. could not have predicted in 1988 what such a conversation in 2016 would sound like or how necessary it would be (even as someone who, in 2009, was arrested for essentially trying to break into his own home), invigorated as it is by social media, by Black Lives Matter and Black Twitter, where outrage and sadness over violence is the order of seemingly every other day.

Can all readers put their shoes on Barnes’ table? The truth is, i be, but i ain’t exhibits an inclusiveness that leads to yes as much as it does a dividedness that leads to no. But do not miss the pleasure of walking into her room.