interviews

Aaron Hamburger’s Grandmother Dressed in Drag to Find Refuge

The author of "Hotel Cuba" fictionalizes his grandmother's journey as a Russian Jew immigrant in 1920s Havana

Aaron Hamburger’s stunning new novel Hotel Cuba imbues the immigrant story with love, sadness, and compassion, breathing new life into the classic genre.

This richly detailed book, set in 1922, is the achingly beautiful story of Pearl, a sober young woman fleeing the chaos of the Russian Revolution with her lovestruck and romantic younger sister. The two women are desperate to get to America, but when discriminatory immigration laws get in their way, they head instead to Havana, Cuba.

All this takes place during the time of Prohibition, when the island is flooded with American tourists eager to drink and indulge in various hedonistic pleasures. The culture shock Pearl experiences during her journey forces her to confront her past and make profound choices that affect her future.

Pearl and her story stayed with me long after I reached the book’s final pages, and so I was eager to speak with the author, Aaron Hamburger who won the Rome Prize in Literature for his first book, The View from Stalin’s Head.

Morgan Talty: Where or how did this book start for you? I’ve heard you talk about drawing from your grandmother’s life story, and I’d love if you could talk about the role your family’s history played in writing this book.

Aaron Hamburger: In my family, we’ve always known that my grandmother, an immigrant from a Jewish shtetl in Russia, spent a year in Cuba before coming to the U.S. and that she was arrested for trying to get into the country illegally via Key West. However, I didn’t appreciate the full dimensions of her story until after the election of 2016 when immigration dominated the news cycle. That’s when it really dawned on hitherto lunkheaded me that my grandmother was an undocumented immigrant.

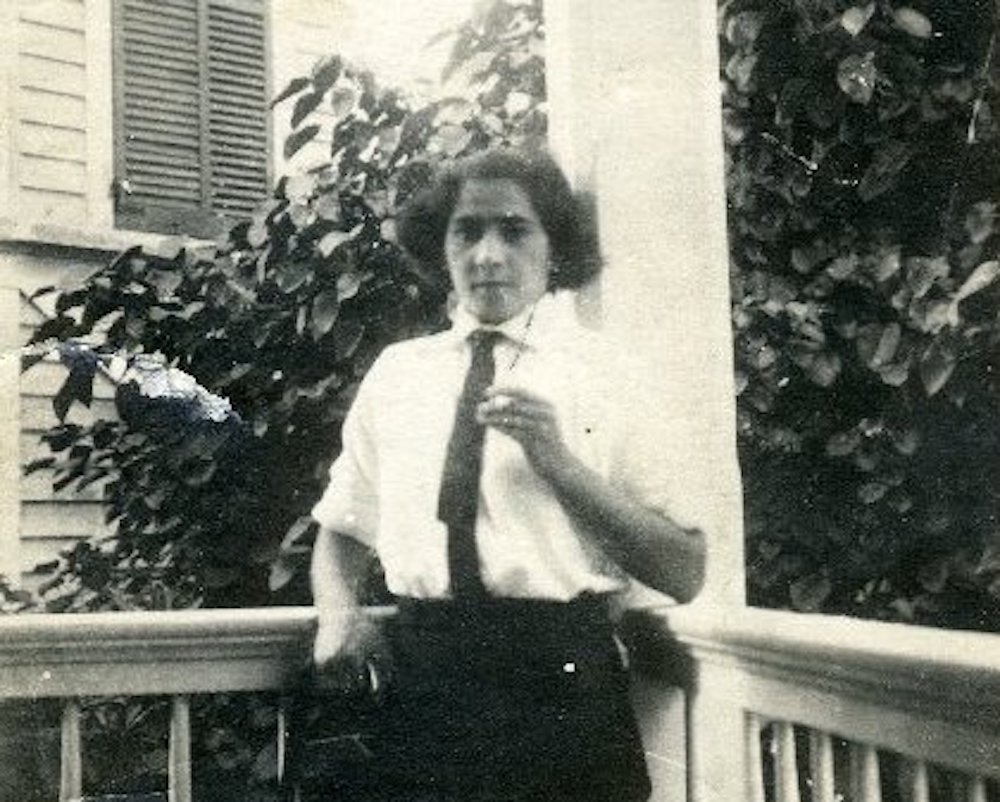

Also in early 2017, I came across an incredibly evocative picture of my grandmother from Key West, at the time of her arrest, in which she was wearing full male drag. This image was so different from the Yiddish-accented grandmother I knew as an old woman.

I was so taken with the picture that I kept showing it to people. When I joined a group of writers advocating for liberal causes on Capitol Hill, I also showed the image to Senator Debbie Stabenow as I advocated for the rights of immigrants. The Senator’s response floored me. She said, “You’re a writer, you have to write your grandmother’s story.”

I had never written historical fiction before, and my first thought was there was no way I could. And then I thought, well, maybe someday I could, but I’ve got other things to do. And then I thought, well, maybe I’ll just try a chapter for fun and see what happens. And then I wrote another chapter. And another. Ultimately I was too fascinated by the story and I simply couldn’t stop.

MT: Hotel Cuba really does read like a renewed type of immigrant storytelling, and I wonder if you could speak a bit to the tradition of immigrant stories and what you think this book brings to the table? Or, in other words, how might this book surprise us about immigrant narratives?

AH: I knew my grandmother, or “Ma” as we called her, as a frail older woman with limited English, whose fondest wish was that someday I might marry a nice Jewish girl. (Sorry about that, Ma, though I did marry a handsome Jewish doctor!) When I saw this picture of my grandmother in a man’s shirt, tie, and pants, I was reminded that she was once young, curious and open to new ideas and experiences just as I had been at that age. I also identified with her as a creative person. In her case, she made clothes; in mine, I make stories.

Another tricky idea out there is that people from earlier times are victims of history, unable to think and feel in complex ways as we do in our so-called enlightened age.

As I started researching this time period, I was impressed by the stories and details I found, how contemporary and modern they sounded. I think there’s this stereotype out there that immigrants from the past are all like the actors in Fiddler on the Roof, simple folk singing about tradition with kerchiefs tied around their heads, but this doesn’t accord with what I found in the historical record. Another tricky idea out there is that people from earlier times are victims of history, unable to think and feel in complex ways as we do in our so-called enlightened age. Oh yeah? Then how do you explain the fact that there were out gay people in Havana in the late 1800s, for example?

I wanted to portray my main character, Pearl, as someone with impulses and feelings we might recognize today, even if her idioms (and therefore her consciousness as it’s affected by language) might be different. For example, I portray Pearl as bisexual in terms of sexual orientation, though she doesn’t use language to label those feelings in the way we might today.

MT: There is so much love in this novel, so much tenderness, yet it is never cloying, and there is also no sense of manipulation—this story is heartfelt in what I would consider all the right moral and ethical ways. It never preys on the reader’s notions of immigrant narratives to achieve a sense of feeling. And so I’m curious: how did you achieve this? Was it a conscious decision or just the way you write?

AH: I approached this story as a writer of literary fiction, struggling to figure out in any given scene what my character might think or sense—not I. What is the best word or sentence structure or paragraph organization to capture Old Town Havana during the rainy season as Pearl might see it, or a how a young woman from a sheltered Russian shtetl might feel trying on pants rather than a dress for the first time? What’s the most accurate word in this particular sentence? Maybe that’s key to the way I write, an insistence of finding the most precise words for what I’m trying to evoke. When the language is false, you can be sure the content or ideas underlying it are false too.

It also helped that I had recordings of my grandparents telling their stories, which I listened to over and over, not necessarily for details of their lives but rather to capture their sensibilities and their idioms. It struck me how insistent they were about very specific details that a casual observer might overlook. For example, my grandfather talked about how when he saw my grandmother for the first time she was wearing a beautiful coat with a fur collar. “I think I fell in love with that coat!” he said. Or later, when my grandmother tried to teach her sister how to cook, her sister confused potatoes and horseradish root. Talking about this fifty years later, my grandfather was still extremely indignant about this. Or when my grandmother described meeting my grandfather and feeling pity for him. “The way he dressed was challushus”—a Yiddish word that means what it sounds like, worse than horrible.

MT: Since you did a lot of research for this book, I’m wondering if you can share with me some details or information you found that didn’t make it into the book?

AH: First, I would have loved to have written more of my grandfather’s story, which was just as dramatic as my grandmother’s. As a young man, he was constantly being sought after by various armies, which would have meant certain death for him as a Jew, given the antisemitism of the time. He had innumerable narrow escapes. Then he managed to reach Warsaw with his younger siblings but couldn’t get a visa, waiting along with the desperate crowds outside the American consulate. However, he heard from someone that he should go to a certain office where there would be a blonde woman at a desk. He was to leave some money on the desk, say nothing, ask no questions. He did. After that, he got the visa.

The fear-based rhetoric around this issue was the same then as it is now. It’s only the places that the immigrants are coming from that have changed.

The most heartbreaking thing I had to exclude from the book is the fate of the characters after the close of the events in the novel. This was included in earlier versions of the book, but ultimately made the story too long and unwieldly. The earlier ending was based on real life: All the Jews in my grandparents’ shtetl (including my grandparents’ immediate families) were killed by the Nazis in World War II. My grandparents heard nothing for a long time, and then the news crossed the ocean. I remember someone saying the phone rang and my grandmother answered it, then let out a loud wail.

Finally, I visited the National Archives to read the correspondence of government agencies at the time, and I was struck by the casual flinging about of vile racist terminology, embedded in flowery formal sentences. I’ll never forget a letter from a dentist in Florida complaining that the government wasn’t doing enough to arrest undocumented immigrants, and he was writing in order to protect the purity of the genetic blood pool of Americans from being contaminated because of immigration. I also held a delicate piece of paper with the most beautiful Chinese writing on it. Then I read the accompanying translation. It was someone reporting to the government about another Chinese person who was in the U.S. without papers.

MT: What were the most challenging aspects of writing this book?

AH: Working on this book was a complete pleasure. I loved the characters, I loved the research, I loved traveling to Cuba and Key West and reading every book I could get my hands on, interviewing scholars and family members. But one challenge was that I had limited information about my grandmother’s true story, and there were gaps that I had to accept I would never be able to fill. (Like why was she dressed in male drag?) I relied on the research and use my best judgment to adopt the most plausible theory I could as to what could have happened. Also, because the book is a novel, I changed the literal truth to make a better and more coherent and convincing story. That’s my responsibility to the reader as a fiction writer.

MT: I feel that so many books situate characters in liminal spaces—placing them neither here nor there, neither where they’re coming from nor where they want to be. One could say these characters are “liminal,” but I’d be hesitant to say such a thing because the book is so deeply detailed and specific. Can you talk a bit about the idea of liminality in immigrant narratives and how Hotel Cuba averts it?

AH: I hear your hesitation about the word “liminal” which seems like a big thing in literature right now. When I was in college, I learned about another hot literary term called “carnivalesque.” Apologies to those who are more conversant in theory than I am as a fiction writer rather than literary critic, but I interpret that term to mean what in Yiddish would be called “a mishmash,” a freewheeling mix of unexpected juxtapositions and combinations. Rather than toeing a line, as perhaps in liminality, the carnivalesque involves blurring the lines, coloring outside the lines, and messing up the lines. I like that kind of creative chaos. I taught English to immigrants in New York for many years, and I saw this dynamic at play, this imaginative mixing of cultures. That’s actually a big part of how English as a language has evolved, through the liberties taken with it by people who don’t feel bound by written and unwritten rules of the language because it wasn’t the one they grew up with.

So whenever opportunities arose in my story to mix and match bits of different cultures, highbrow culture and pop culture, male culture and female culture, I grabbed them. For example, I read about Jewish immigrants in Cuba supporting themselves was by selling Christian religious icons. Androgyny was “in” in the fashion of the period. Also, one of the ways that women without papers got into the U.S. was by cross-dressing as sailors. All these kinds of details were interesting and welcome to me as I wrote.

MT: What do you hope readers take away from the novel?

AH: I’m going to be a total hypocrite here. As a writing teacher, I frequently warn my students not to structure their stories in order to express some kind of message. Kind of like the famous Jack Warner (of Warner Brothers Studios) used to say, “If you want to send a message, call Western Union!” How ironic, given that Warner Brothers, in the Golden Age of Hollywood, was known as a studio for producing socially conscious movies. I want Hotel Cuba to be a beautiful story, a moving story, an exciting story, but also a story that reminds us of the profound everyday courage exhibited by immigrants. So can we maybe as a society stop scapegoating them?

There but for the grace of God go I. If my grandfather had not broken the law by bribing someone in Warsaw and if my grandmother had not broken the law by making the journey she made as an undocumented immigrant, Hotel Cuba and the rest of my books would not exist. In fact, I wouldn’t be alive because my mother would have been rounded up with her fellow townspeople in Russia and shot by the Nazis—as the adult men were—or locked in a building and burned alive—as the women, children, and elderly were.

When people leave their homes, it’s for a reason. I understand the desire to create and debate fair rules and systems, but what I don’t understand is the harshness, hard-heartedness, and callous fearmongering that prevents us from having a rational discussion about immigration just as it did in the 1920s. Do the research. The fear-based rhetoric around this issue was the same then as it is now. It’s only the places that the immigrants are coming from that have changed.