Lit Mags

A New Story by the Master of Hardboiled Detective Fiction

“The Glass That Laughed” by Dashiell Hammett

AN INTRODUCTION BY RICHARD LAYMAN AND JULIE M. RIVETT

November 1925: Dashiell Hammett is thirty-one years old with a pregnant wife, a four-year-old daughter, and a tubercular illness that fluctuates between barely manageable and debilitating. He is living on the edge financially and his primary source of income, along with VA disability payments, comes from his stories in Black Mask magazine, whose editor seems to him stingy and officious. Attempting to broaden his literary base and fatten his meager earnings, he had that year published two stories in Sunset, a magazine that promoted tourism on the Pacific Coast while promising its readers “the best fiction money will buy.” He wrote reviews and criticism for The Editor and The Forum, publications with a more literary readership that encouraged debate on issues related to the liberal arts. And he published poetry in The Lariat, a little magazine devoted serious verse. He was desperate for a paycheck, however small.

“About half of the fiction I have written has had to do with crime, though, curiously, I was some time getting the hang of the detective story.”

In the May 1925 issue of The Editor, Hammett summed up his writing career to that point: “About half of the fiction I have written has had to do with crime, though, curiously, I was some time getting the hang of the detective story. And while, with the connivance of the Black Mask, that type of story has paid most of my rent and grocery bills during the past two years, I have sold at least one or two specimens of most of the other types to a list of magazines, varied enough if not so extensive.”

Four decades of devoted research — combing copyright records; editing Hammett’s correspondence; visiting and studying his manuscript archive at the Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin; interviewing family members, Hammett’s secretaries, and associates — uncovered Hammett publications in fourteen magazines aside from Black Mask. We thought we had found them all.

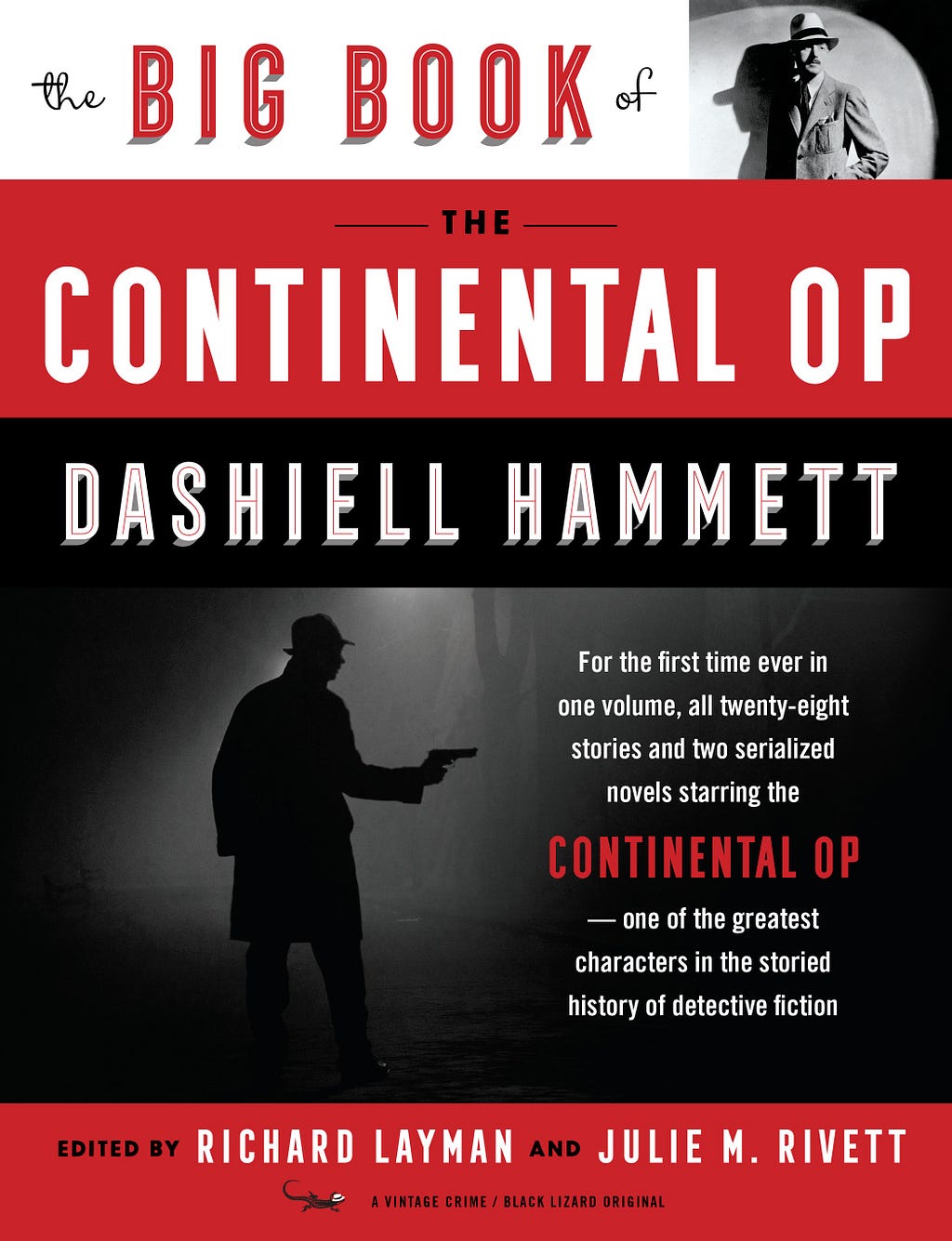

Then, in September 2017 Hammett’s granddaughter, Julie Rivett, co-editor with me on The Big Book of the Continental Op, sent an email saying she had just read a notice on the Dashiell Hammett Reading Group Facebook page posted by Kevin Burton Smith, founder of The Thrilling Detective Web Site, stating that an unnamed fan had come across a previously unrecorded story by Hammett in True Police Stories. The title, “The Glass That Laughed,” and the magazine were unfamiliar to us. Julie asked Kevin to put us in contact with his correspondent. The next day I received a call from Daniel Robinson, a fireman and author, who agreed to sell me the November 1925 issue of True Police Stories, a short-lived magazine published monthly from May 1924 to April 1926 “under the auspices of the International Police Conference” as an “organ of the New York Police Department.” Three days later the package arrived. It was Hammett all right.

The original publication of “The Glass That Laughed” is destined to be preserved in the Dashiell Hammett Collection at the Thomas Cooper Library, University of South Carolina. With pleasure, we offer the story to you here.

Richard Layman and Julie M. Rivett

Editors, The Big Book of the Continental Op

A New Story by the Master of Hardboiled Detective Fiction

Dashiell Hammett

Share article

“The Glass That Laughed”

by Dashiell Hammett

Conscience prompts hallucination and weird phantoms make an end

Moonlight, slanting through the window, became a white pattern on the floor of the room in which Norman Bacher awakened. The carafe on his bedside table was empty; he had drunk often that restless night. Fumbling for his slippers, he got out of bed. The bureau’s mirror threw a reflection at him.

In the dim light, hair rumpled, face paler than ordinary, the face in the glass was too like Eric’s not to startle Norman. He brushed a hand across his forehead and blew his breath out sharply. What had for an instant been a dark stain on the mirrored brow was only a pendant lock of hair. He studied the face in the glass until his pulse was steady. Then he went for his water and returned to bed. But he could not sleep.

He knew that what remained of his brother would never be found, never searched for. He knew no one could suspect him of having murdered his brother. Eric Bacher and some fifteen thousand of the bank’s dollars had vanished simultaneously. Reckless spendthrift Eric, with his weakness for gambling, always deep in debt, taken into the bank a few months ago only because his brother earnestly requested it. There were people — many — in Bradton who preferred Eric’s society to Norman’s, but not even the fondest of them could suspect Norman of any part in the vanishing of his brother and the money. Thrifty, industrious Norman, with thirty years of sober drabness and twelve years of faithful service in the bank to his credit. Certainly there was little likelihood of disaster from without. From within — he had provided against that too.

He knew himself down to his least weakness, and he had planned his crime with adequate allowance for each quirk of his nature. Nights of sleeplessness, gusts of cowardice, even the occasional remorse that could be routed only by thinking of what the stolen thousands meant to him — they were not to buy folly, those dollars, but to start him toward the wealth and power of which he dreamed — all these things he had considered and weighed and measured before he had acted. But there was this thing he had not foreseen.

Neither of the Bacher twins had ever been mistaken for the other. The most casual acquaintance could not have made that mistake. Norman’s face was pale, grave, with the compressed, secretive mouth and steady eyes of the young man whose career is a serious thing. Eric’s face had color, was mobile, and his mouth was always either open or about to open — a great talker and laugher. Nevertheless, their features — seen when sleep, say, had robbed them of their daytime expressions — were much alike. The differences were all in the pulling here and there of muscles at the behest of two identities that were as far apart as only brothers can be. In unconsciousness one brother’s face was the other’s, except for coloring. Eric had pink skin and a red mouth.

But Eric’s face, just before the bullet had struck, and just after, had been twisted and blanched — first by fear and then by a spasm of brief pain, perhaps — into a mask that would better have become his brother. Norman had seemed to look into his own face dying with Eric’s body. In his mind had remained the impression of his own face distorted by the fear of death — no stranger to him — with a red spot in the forehead where a metal pellet had been driven into Eric’s brain. It was Eric who had been shot and who had died, but through Norman’s brow, the blood had trickled down Norman’s face.

Twice within the day this dying face had looked at Norman; from a store window on Broadway this afternoon, and now from the bureau mirror, made terribly real this time by the counterfeit scar on the forehead. Hope said that this seeing dead Eric in his own likeness was a trick of overwrought nerves, a trick that would lose its horrible effectiveness as his nerves gradually relaxed into normal steadiness. Fear said that through this trick too-taut nerves would destroy themselves and their owner; that each repetition of the illusion would increase the tension, that the greater the tension became, the more frequent and real would the illusion be — until the inevitable collapse.

Were hope right, or were fear, Norman Bacher knew he could not hide from this thing. All his planning had been based upon the principle that shadows pursue fastest when fled from. He got out of bed and sat in the moonlight before the bureau, looking into the down-tilted glass. This illusion had to be forced down if disaster were to be avoided; he knew himself to the least weakness. After a while he slept, his head against the chair back. He had seen nothing in the glass except his own face. Later he awakened with a stiff neck and went back to bed.

Twice the next day he saw Eric’s dying face — in a window of the bank, and in a chewing-gum machine on First street. Each time he faced the reflection until he was steady-nerved in the assurance that it was his own and not his brother’s face. He bought a green eye-shade. His desk at the bank faced a window that became a dim mirror when the awning was lowered in the afternoon. He had not yet seen Eric’s face in that window, and did not wish to.

Coming home from the bank that same afternoon he took his first definite step in flight from his dead brother’s face. The mirrored chewing-gum machine in First street was in his path. Approaching, he kept his eye steadily upon it until he came abreast. Then he spied Mrs. Dunan, the bank president’s wife, coming toward him. He hastily looked away from the mirror. He feared that if he saw Eric in the glass this second time he might be startled into some momentary gesture of betrayal. So he turned his eyes toward Mrs. Dunan, and lifted his hat — but in the very act of averting his eyes from the mirror he had caught a flash of Eric’s face. He went on, walking fast, for the first time running from the illusion. After that he was never to be certain that it was an illusion.

That was Saturday. He stripped the house of its mirrors that night and piled them in the cellar. At midnight he went to the cellar again and brought four of the largest mirrors up to his bedroom, where he propped one against each wall. In the center of the room he sat on a chair, and turned his face from mirror to mirror, looking into the four reflections of a face that was unmistakably his own. It was after daylight when he gave it up and got into bed. As he raised his head to adjust the pillow more comfortably under it, Eric’s white face looked at him. It was not Eric’s face when he sat up in bed and peered through the thinning dusk at the glass. It was his own. All day Sunday he prowled through the house in which his brother had died; upstairs and downstairs, ceaselessly, aimlessly, he walked; from the dusty attic to the damp cellar, with its pile of broken glass where he had worked with an ax on the mirrors. Every light burned, and everything that could cast a reflection was covered by a rug, curtain, sheet, towel, or cloth of some sort. The tow attic windows had no blinds. He had turned away to find covering for them, but had been afraid of what they might show him when he returned. A candlestick lay on a trunk nearby. He broke the glass out of the windows with it.

Shortly after midnight he was in the cellar poking at the ruined mirrors until he had a triangular fragment large enough to give him back his face. Carrying it upstairs, he stood it against two books on a table. He sat down and stared into it, elbows on the table, face on hands. As he sat looking into the face that was so certainly his own and not his brother’s, his eyes became fixed with hypnotic rigidity. He could have wrenched them away only with severe effort, but he made no effort. All of him was centered on what showed in that ragged bit of glass. His breathing became heavy and mechanically spaced. His eyes turned upward and outward, though the lids did not close.

Sometime later he came to with a convulsive start. The glass reflected his own face, white and harried and unscarred of forehead. He resumed his staring — he had dozed for an instant, perhaps, dreaming. . . . Through the silent earliness of Monday morning came the striking of the City Hall clock. He did not hear it. His eyes were focused glassily, unswervingly on the glass. The clock struck again, later hours. The sun crept around the drawn blind and laid parallel strips of gilt on the floor. He neither heard nor saw.

An elbow slipped. His head dropped, knocking the mirror over. He jumped to his feet, upsetting the chair, crying aloud in crazy terror. Then he looked around the lightening room and laughed jarringly. The night had passed. Nothing had happened. He felt suddenly childish, silly, ashamed of the seriousness with which he had taken the illusions.

Something tickled the bridge of his nose. His hand came away red. A stinging was in the center of his forehead. He snatched up the mirror. Eric’s face, white and twisted by terror, looked at him. From the hole in Eric’s forehead blood still trickled.

Screaming, Norman Bacher bolted out of the house. Two men — a telegraph operator and a brakeman — were across the street, walking toward the station. He dashed over to them and began shrieking his confession into their astonished faces. He gestured wildly. The triangular piece of looking-glass — its dagger-sharp apex stained freshly red — sailed out of his hand, and shattered on the sidewalk with a tinkling that was like the distant laughter of children.