Interviews

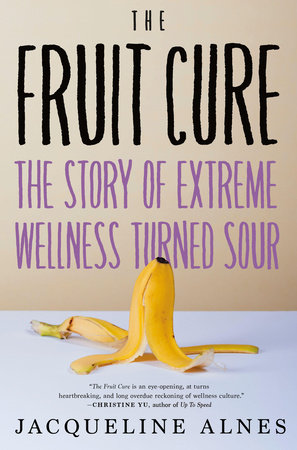

Writing an Illness Story that Rejects the Inspirational Healing Narrative

Jacqueline Alnes’ book "The Fruit Cure" delves into online wellness culture, and the power of stories we inherit—and tell ourselves—about our bodies

“When you are in the throes of illness,” Jacqueline Alnes writes in her debut The Fruit Cure: The Story of Extreme Wellness Turned Sour, “there is something comforting about distilling the world into dichotomies: sick or well, bad or good, off-limits or completely nutritious. When so much seems unknowable about the very body you live in, it feels nice to stand on a firm platform made from rights rather than wrongs, even if the very platform itself is a false reality.” As a Division I collegiate runner, Alnes began experiencing mysterious and devastating neurological symptoms that remained unexplained by medical doctors for years. Amidst the frustration of living without a clear diagnosis and treatment path, and the grief of a troubling departure from her team and sport, Alnes found refuge in an online community that proselytized an extreme diet—consisting only of fruit—as a cure for most anything.

One-part memoir, one-part narrative nonfiction, one-part historical investigation, The Fruit Cure takes readers on a journey through the sometimes-sinister past—and controversial present—of extreme wellness communities on the Internet. With the deft of an investigative journalist, the nuance of a historical and cultural critic, and the craft of a memoirist, Alnes subjects herself to the same rigor of inquiry as the wellness gurus and devout followers she researches, asking difficult questions about responsibility, narrative, and power. Resisting a convenient slide into the very dichotomies of good and bad, ill and healed, that she unearths in these spaces, the result is a read that is empathic and tender, at times darkly humorous, and ultimately deeply inhabitable for anyone who has lived in a body and grappled with the impossibility of its control.

Jacqueline Alnes, an assistant professor of English at West Chester University, whose work has been published in The New York Times and Guernica, joined me on Zoom to discuss the moralization of food, parasocial relationships, ableism, running, and the challenge—and freedom—of writing an illness narrative that rejects inherited myths about healing and cures.

Alexandra Middleton: You write openly in The Fruit Cure about the challenge of reliving memories of your neurological illness when memory itself was elusive. What was it like for you to revisit these memories through writing this book?

Jacqueline Alnes: Feeling like I could write about this was an interesting conversation I had with myself. I don’t have a memory of it like you would traditionally a memory. For the sake of my own self-preservation, I tried to pretend a lot of it didn’t happen. Which is part of the crux of the book: if you do that, you harm yourself because you haven’t addressed the thing that actually hurts you. Writing was a step of owning the story, saying, “Yes, this did happen to me,” then asking “What does that mean about how I feel about myself? About my body? About the way I feel I can let other people care or not care for me?” The book is an act of vulnerability, saying, “Here’s the story I haven’t told to myself for so many years.” It’s been sometimes difficult, sometimes joyful, sometimes terrifying.

AM: A chapter in the book shares the same title as your Ph.D. dissertation, which engaged literature on illness narratives, disability studies, and women in pain: Well Developed Female in No Acute Distress. How did your PhD research inform what ultimately became The Fruit Cure?

The publishing industry has valued narratives where the person is an inspiration at the end. I resisted that and thought, how could I write a narrative about not being fully healed?

JA: Part of it was a resistance to illness narratives. Not all of them; I don’t want to say something click-baity like “she hates illness narratives!” But many felt like the person was okay on the other side. I remember reading and feeling, “Wait. Am I not okay then? Have I just not been able to get over it?” Because it had been ten years since I was seriously ill and I still hadn’t fully left the ghost of that illness behind. The publishing industry, historically or culturally, has valued narratives where the person is an inspiration at the end. I resisted that and thought, how could I write a narrative about not being fully healed or on the other side with your feet firmly planted in able-bodiedness again? Can you still find joy and meaning, and acknowledge a sadness or grief or a ghost in your life? That was a narrative I wanted to read, and that I hope I wrote. Some of the scholarship I read during my PhD made it in because I couldn’t have written The Fruit Cure without thinking about the way we all are harmed by narratives given to us about what it means to have disability and what it means to be able-bodied.

AM: Definitely. I think many people will identify with your story about the frustrations and grief of falling through diagnostic cracks in a healthcare system that’s not always equipped to address complex illness, not always patient-centered, not always oriented to lived experience. You deliver a critique of vigilante self-care and unregulated alternative treatments under the banner of wellness that step in to fill these gaps. And yet there’s also a sense of meaning, validation, and agency people seem to locate in these alternative spaces that’s not entirely recuperable in the traditional medical system. Can you elaborate on the rift between wider systemic issues in U.S. healthcare and the allure of wellness culture?

JA: You hit on what honestly was one of the hardest things to write about in the book. I in no way want to say either is good or bad. Thinking about how many people are failed on a regular basis by U.S. health care systems, it feels totally valid that someone would click on a link to fast for 30 days to cure their diabetes, which I react viscerally to on surface level. But on a human desperation, I want to feel well and these systems are failing me, charging me thousands of dollars a month for very little care, level? 100% get it.

Writing into it, I was trying to advocate for people to know their bodies best. Alternative healing sometimes offers that sense of agency where if you know your body well and someone else is saying, “Yes, I believe you,” there’s real power to that. There is power in the narratives you have about your own body and the narratives someone else can give you about your body. If you’re being told you’re a puzzle or a mystery, or that your pain is not real or valid, that affects you. My main critique is of people who don’t realize their own influence and power in those spaces. And when people are being harmed and speaking up, there is an alarming lack of self-reflection in some people, when you have the well-being of another person in your hands.

AM: Yeah, absolutely. And it happens in both those worlds, too.

JA: Right. That’s what’s hard. I totally get why people wouldn’t believe in Big Pharma. I mean, it’s, horrendous. “We’re making profit from your illness.” I also see the lack of trust of, “take this weird powder and you’ll heal everything.” Both ends are so fraught with potential missteps or ways you could be influenced in a harmful direction that doesn’t help you heal yourself.

AM: And perhaps accumulates other things to heal along the way. In the absence of a clear path of medical treatment, you took your healing into your own hands through two means primarily: food and running. I want to focus first on food. The connections you drew between the high-carb raw vegan movement and religious ideologies fascinated me. What makes food such a compelling battleground for moral reckoning, personally and collectively?

There is power in the narratives you have about your own body and the narratives someone else can give you about your body.

JA: On a personal level, it came from a desire to want to be good. I no longer had external measures of grades, miles splits. I felt like if I ate these foods, I would be like they told me on the internet: a clean, bike-riding, beautiful acne-free person. In some ways they just condensed all the world’s rhetoric and gave it to me. We hear it all the time: this yogurt is “not sinful” or this is a “guilt-free” snack, or in a workout class someone’s telling you summer is coming. We’ve moved a bit past that, but I think it’s just coded differently so we don’t hear things we know were problematic in the early 2000s. My focus is on women, because a lot of the people I interviewed and who participated in the fruit diet were younger women searching for the “perfect body” and I think there’s something in that in terms of what spaces people feel like they can control. Food is available to all of us as a form of exercising control and partitioning what we do or don’t do, sometimes in harmful ways.

AM: The historical dimensions of your research really contextualized “how did we get here?” especially as you address the whiteness of the vegan influencing world and the racist, white supremacist origins of thinness, implicitly embedded in ideals of able-bodiedness. Did anything surprise you when you delved into this history?

JA: So much surprised me and wasn’t all so surprising at the same time. Sabrina String’s book, Fearing the Black Body, really helped me in thinking about racism and whiteness. She wrote about Lady Mary Wortley, and the idea that white women wanted to be thin to separate themselves from black women at the time. It was horrifying to read and to see the ways that framing was echoed in the following texts. I remember reading the Arnold Ehret section about how women could be more Madonna-like if they lost their periods just eating fruit. That was something he celebrated. Now we would frame that as disordered eating, amenorrhea, we need to get you restored and back to health. And he viewed it as being even more pure and holy. Those didn’t just become abstract moral concepts; they had direct impacts, again, mostly on women’s bodies. He’s not talking about men abstaining to the point of gauntness; he’s saying this is what women should do. That became fascinating in a really horrifying way, thinking about how long women especially had been hearing these messages about keeping yourself pure, not only sexually, but also religiously, morally.

AM: I want to talk to you about influencers. I’m thinking about the double entendre of the word “follower,” in context of the relationship you point out between religiosity, morality, and extreme online food communities. Can you say more about the intersection of parasocial relationships, authority, and health in an age where so many of us are seeking answers online?

JA: There are beautiful things about social media. We get insights into each other’s lives; it’s a form of intimacy and comes from a place of curiosity. But there’s a dark side to it too. Once there’s a setup of “this is what I do, and you should also do it,” that person has a responsibility to know their rhetoric has a direct impact on another’s health, physical or mental, or perceived relationship with food. When does that responsibility begin and when does it end? Is there a way to be an influencer responsibly online, around food? As the dieticians I interviewed said, it’s not very sexy or clickbait to say “Everybody’s different, we have to figure it out with you.” It’s way more fun and engaging to say, “I have the answer. Come on, let’s go.” Our social media platforms privilege our attention to wanting easy answers rather than puzzling out all the different factors that make us who we are and make us eat as we do.

AM: You reached out to Freelee and Durianrider, the influencers behind the fruitarian community you followed, for an interview, which never materialized. So you drew upon their public profiles and content in the book, making clear you weren’t mistaking these mediations for intimacy or interiority. If you could ask them one question, what would it be?

I felt like if I ate these foods, I would be like they told me on the internet: a clean, bike-riding, beautiful acne-free person.

JA: I want to know how they really feel about fruit. I have this hunch that they really, truly, did believe in fruit when they first started this diet. Are they still seeking these ideals of purity, even though they’ve changed the name of the game? Do they feel like social media has kept them beholden to these figures they’ve created for themselves online? Does it matter in the end that I don’t know who you are? In our age of social media, who you are online is a part of you. And that persona is what you’re choosing to give to me as a viewer. What am I to do with that? I guess that was ten questions for them. I hope I treated them with empathy and care because as people, I do care about them and want their perspectives and nuance to be heard.

AM: You write about the seduction—but ultimate emptiness and sometimes danger—of dichotomies such as “good and bad” and “sick and well.” Do you think of healing and cure as existing in dichotomies of any sort? What does living outside those dichotomies look like for you today?

JA: Some of the stuntedness of my healing came from the perception that you were either sick or you were well. I did not believe there was a gray area. Culturally, ideas of cures as a quick fix can be so harmful for that reason. It’s why we reach for them. Someone asked me recently, what ended up being the cure for you? And I said, mess, the greatest mess. Therapy and nutrition and seeing doctors who started listening to me and sitting with my own discomfort and thinking about the narratives about disability I had believed and undoing them and figuring out what stories about my body were mine, and which had come from other people, and what that meant. I love now thinking about healing and cures as nuanced, as spectrums, as being in the gray. That’s been the most honest way to find hope in my body again.

AM: That feels so real, hopeful, palpable. Expecting ourselves to remain in one state feels so overwhelming to uphold. But if healing can be a state of flux, a state that includes what maybe we wouldn’t consider “fully healed”? That sounds so much more possible.

JA: That’s so true.

AM: I’m curious how running figures into the matrix of healing in The Fruit Cure. There’s clearly so much passion and self-expression; running is this life force channeling through you, a reason to heal. And yet I noticed parallels with how you wrote about fruit: devotion, salvation, hunger, obsession, self-discipline. Many of us who run have some relationship with that paradox, I certainly do. Can you discuss this paradox and the evolution of your relationship with running?

JA: A lot of messaging I received as a young runner, and I blame the system all my coaches came up in rather than any one coach, was “the less you acknowledge your body, the better.” From a formative age, I tied this dismissal of body with accomplishment in sport. When I got sick, my first instinct was to ignore my symptoms and try to keep running because that’s what my coach told me to do. My second impulse after I quit the team was to be angry at my body that I could run, which turned to: how can I punish myself through this thing I used to love?

Our social media platforms privilege wanting easy answers rather than puzzling out all the different factors that make us who we are.

I didn’t reckon with the ways I was using running as a weapon and as a salve until my PhD years, almost a decade after I’d first been sick. I was chasing this version of myself I thought existed: the girl who was the inspirational end to an illness narrative. She was the fastest, strongest, never had a symptom, ignored pain. I wanted to be her so badly because I thought she did exist out there. It took finally realizing I was chasing this illusion of myself to realize I could give her up and just live in my own body and explore what that meant. I’m not going to say it was easy, but I have come to a place where if I’m not having fun, I don’t do it. I still compete, I have fun chasing goals because that’s an impulse we all share as distance runners: to keep testing your own limits. But I do it now from a safe loved place rather than from a place of fear or shame or wanting something I don’t have.

AM: I love how the resolution of the illness narrative melds with this archetype of the invincible runner, to link back to how we began. You’ve defined your own, Jacqueline-runner now, that is a rejection of that narrative, and maybe because of that finds joy in the sport. That’s powerful for runners to read, because for many of us, if you’re in this sport long enough, it either will consume you at some point or you’ll have to reckon with these parts of yourself that are searching for something.

JA: Right? That joy allowed me to be in community again. I run with people four times a week now. I care about them and they care about me. That has been really healing in terms of my experiences on the team, this heartbreak I hadn’t been able to address.

AM: Reading The Fruit Cure I thought how much of a resource this book would have been for a college age Jacqueline, but also college age Allie. And for anyone living with complex illness or without a diagnosis, in the throes of complicated relationship with food, disordered eating, exercise, control, and/or under the influence of the Internet. To any of these readers: what do you hope this book will offer?

JA: I used to feel so lonely with those feelings. But looking at history made me realize, no. There was a woman in South Africa in the 1960s, Essie Honiball, feeling the same way, due to similar cultural forces I am facing that are now just on Instagram, rather than in some pamphlet or from some pseudoscience doctor in a back room of a house. It made me feel if I understand narratives perpetuated for centuries, from biblical times, about epilepsy or neurological issues or bodies being out of control, then I can start to ask, which ones do I want to accept and which ones do I want to reject? That is true form of power. Rather than reaching for illusions of power through: “How thin can I be? How fast can I run? What kind of foods am I eating?” My hope is that people realize they’re genuinely not alone. All of us in some way are impacted by these things, even if we’re not chronically ill, even if we don’t have disordered relationships with food. We’re all shaped by the stories told to us.